Attribution: You Keep Using That Word, I Do Not Think It Means What You Think It Means…

In internal discussions in virtual halls of IOActive this morning, there were many talks about the collective industry’s rush to blame or attribution over the recent WanaCry/WannaCrypt ransomware breakouts. Twitter was lit up on #Wannacry and #WannaCrypt and even Microsoft got into the action, stating, “We need governments to consider the damage to civilians that comes from hoarding these vulnerabilities and the use of these exploits.”

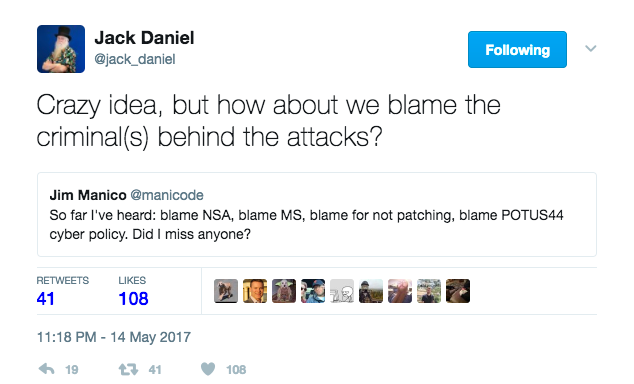

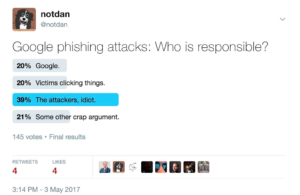

Opinions for blame and attribution spanned the entire spectrum of response, from the relatively sane…

As a community, we can talk and debate who did what, and why, but in the end it really doesn’t matter. Literally, none (well, almost none) of us outside the government or intelligence communities have any impact on the discussion of attribution. Even for the government, attribution is hard to nearly impossible to do reliably, and worse – is now politicized and drawn out in the court of public opinion. The digital ink on malware or Internet attacks is hardly even dry, yet experts are already calling out “Colonel Mustard, Lead Pipe, Study” before we even know what the malware is fully capable of doing. We insist on having these hyperbolic discussions where we wax poetic about the virtues of the NSA vs. Microsoft vs. state actors.

It’s more important to focus on the facts and what can be observed in the behavioral characteristics of the malware and what organizations need to do to prevent infection now and in the future.

How people classify them varies, but there are essentially three different classes of weaponized malware:

- Semi-automatic/automatic kits that exploit “all the things.”These are the Confickers, Code-red, SQL Slamming Melissa’s of the world

- Manual/point targeted kits that exploit “one thing at a time.” These are the types of kit that Shadow Brokers dropped. Think of these as black market, crew-served weapons, such as MANPADS

- Automatic point target exploit kits that exploit based on specific target telemetry AND are remotely controllable in flight. This includes Stuxnet. Think of these as the modern cyber equivalent of cruise missiles

Nation state toolkits are typically elegant. As we know, ETERNALBLUE was part of a greater framework/toolkit. Whoever made WannaCrypt/Cry deconstructed a well written (by all accounts thus far) complex mechanism for point target use, and made a blunt force weapon of part of it. Of those three types above, nation states moved on from the first one over a decade ago because they’re not controllable and they don’t meet the clandestine nature that today’s operators require. Nation states typically prefer type two; however, this requires bi-directional, fully routed IP connectivity to function correctly. When you cannot get to the network or asset in question, type three is your only option. In that instance, you build in the targeting telemetry for the mission and send it on its way. This requires a massive amount of upfront HUMINT and SIGINT for targeting telemetry. As you can imagine, the weaponized malware in type three is both massive in size and in sunk cost.

WannaCry/WanaCrypt is certainly NOT types two or three and it appears that corners were cut in creating the malware. The community was very quick in actively reversing the package and it doesn’t appear that any major anti-reversing or anti-tampering methods were used. Toss in the well-publicized and rudimentary “kill switch” component and this appears almost sloppy and lacks conviction. I can think of at least a dozen more elegant command and control functions it could have implemented to leave control in the hands of the malware author. Anyone with reverse engineering skills would eventually find this “kill switch” and disable it using a hex editor to modifying a JMP instruction. Compare this to Conficker, which had password brute-forcing capabilities as well as the ability to pivot after installation and infect other hosts without the use of exploits, but rather through simple login after passwords were identified.

This doesn’t mean that WannaCry/WanaCrypt is not dangerous, on the contrary depending upon the data impacted, its consequences could be devastating. For example, impacting the safety builder controlling Safety Instrumented Systems, locking operators out of the Human Machine Interfaces (HMI’s, or computers used in industrial control environments) could lead to dangerous process failures. Likewise, loss of regulatory data that exists in environmental control systems, quality systems, historians, or other critical ICS assets could open a facility up to regulatory action. Critical infrastructure asset owners typically have horrific patch cycles with equally appalling backup and disaster recovery strategies. And if businesses are hit with this attack and lose critical data, it may open up a door to legal action for failure to follow due care and diligence to protect these systems. It’s clear this ransomware is going to be a major pain for quite some time. Due care and preventative strategies should be taken by asset owners everywhere to keep their operations up and running in the safest and secure manner possible.

It really doesn’t do much good to philosophically discuss attribution, or play as a recent hashtag calls it, the #smbBlameGame. It’s relatively clear that this is amateur hour in the cybercrime space. With a lot of people panicking about this being the “next cyber cruise missile” or equivalent, I submit that this is more akin to digital malaria.