Day by day the endless fight between the bad guys and good guys mostly depends on how fast a countermeasure or anti-reversing protection can be broken. These anti-reversing mechanisms can be used by attackers in a number of ways: to create malware, to be used in precompiled zero-day exploits in the black market, to hinder forensic analysis, and so on. But they can also be used by software companies or developers that want to protect the internal logic of their software products (copyright).

The other day I was thinking: why run and hide (implementing anti-reversing techniques such as the aforementioned) instead of standing up straight and give the debugger a punch in the face (crashing the debugging application). In the next paragraphs I’ll explain briefly how I could implement this anti-reversing technique on ELF binaries using a counterattack approach.

ELF executables are the equivalent to the .exe files in Windows systems, but in UNIX-based systems (such as Linux and *BSD). As an executable file format, there are many documented reversing [1] and anti-reversing techniques on ELF binaries, such as the use of the ptrace() syscall for dynamic anti-debugging [2]:

void anti_debug(void) __attribute__ ((constructor));

void anti_debug(void)

{

if(ptrace(PTRACE_TRACEME, 0, 0, 0) == -1){

printf(“Debugging not allowed!n”);

exit(0xdead);

}

}

Trying to debug with GNU debugger (the most famous and commonly used debugger in UNIX-based systems) an ELF executable that contains the above code will result in:

However, as can be seen, even with the anti-debugging technique at runtime, the ELF file was completely loaded and parsed by the debugger.

The ELF files contain different data structures, such as section headers, program headers, debugging information, and so on. So the Linux ELF loader and other third party applications know how to build their layout in memory and execute/analyze them. However, these third party applications, such as debuggers, sometimes *TRUST* on the metadata of the supplied ELF file to be analyzed, and here is where the fun begins.

I found one bug in GNU gdb 7.5.1 and another one in IDA Pro 6.3 (the latest versions when this paper was written), using Frixyon fuzzer (my ELF file format fuzzer still in development). To explain these little bugs that crash the debuggers, we’ll use the following code (evil.c):

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

printf(“It could be a malicious program }:)n”);

return 0;

}

Crashing GNU gdb 7.5.1

Compiling this with gcc using the –ggdb flag, the resulting ELF file will have section headers with debugging-related information:

After a bit of analysis, I found a bug in the DWARF [3] (a debugging file format used by many compilers and debuggers to support source-level debugging) processor that fails when parsing the data within the .debug_line section. This prevents gdb from loading an ELF executable for debugging due to a NULL pointer dereference. Evidently it could be used to patch malicious executables (such as rootkits, zero-day exploits, and malware) that wouldn’t be able to be analyzed by gdb.

In gdb-7.5.1/gdb/dwarf2read.c is the following data structure:

struct line_header

{

…

unsigned int num_include_dirs, include_dirs_size;

char **include_dirs;

…

struct file_entry

{

char *name;

unsigned int dir_index;

unsigned int mod_time;

unsigned int length;

…

} *file_names;

}

The problem exists when trying to open a malformed ELF that contains a file_entry.dir_index > 0 and char **include_dirs pointing to NULL. To identify the bug, I did something called inception debugging: to debug gdb with gdb:

The root cause of the problem is that there’s no validation to verify if include_dirs is different from NULLbefore referencing it.

To simplify this process, I’ve developed a tool to patch the ELF executable given as an argument,

gdb_751_elf_shield.c:

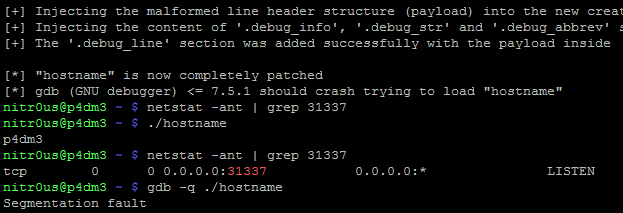

After patching a binary with this code, it will be completely executable since the operating system ELF loader only uses the Program Headers (not the Section Headers). But, it wouldn’t be able to be loaded by gdb as shown below:

T

Timeline:

12/11/2012 The bug was found on GNU gdb 7.5.

10/12/2012 Retested with the latest release (7.5.1), which still has the bug.

12/12/2012 The status on the tracker is still “NEW”.

C

Crashing IDA Pro 6.3

The IDA Pro ELF loader warns you when it finds invalid or malformed headers or fields, and asks if you want to continue with the disassembly process. However, there’s a specific combination of fields that makes IDA Pro enter an unrecoverable state and closes itself completely, which shouldn’t happen.

The aforementioned fields are found in the ELF headers, e_shstrndxand e_shnum, where the first one is an index of the Section Header Table with e_shnumelements. So IDA will fail if e_shstrndx > e_shnum because there is no validation to verify both values before referencing it.

The following screenshot illustrates the unrecoverable error:

I have also programmed a simple tool (ida_63_elf_shield.c) to patch the ELF executables to make them impossible for IDA Pro to load. This code only generates two random numbers and assigns the bigger one to e_shstrndx:

srand(time(NULL)); // seed for rand()

new_shnum = (Elf32_Half) rand() % 0x1337;

new_shstrndx = (Elf32_Half) 0;

while(new_shstrndx < new_shnum)

new_shstrndx = (Elf32_Half) rand() % 0xDEAD;

header->e_shnum = new_shnum;

header->e_shstrndx = new_shstrndx;

After patching a file, IDA will open a pop-up window saying that an error has occurred and after clicking the OK button, IDA will close:

imeline:

21/11/2012 The bug was found on IDA Demo 6.3.

22/11/2012 The bug was tested on IDA Pro 6.3.120531 (32-bit).

22/11/2012 The bug was reported through the official Hex-Rays contact emails.

23/11/2012 Hex-Rays replied and agreed that the bug leads to an unrecoverable state and will be fixed in the next release.

A real life scenario

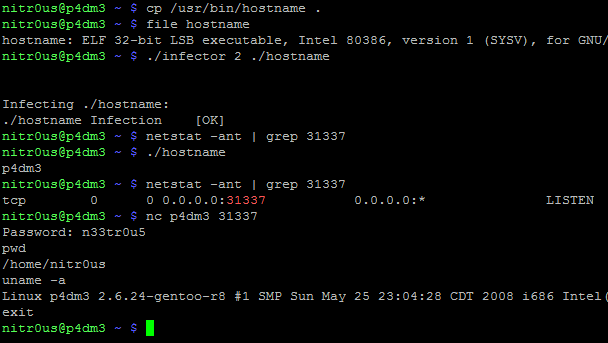

Finally, to illustrate that neither patching tool will corrupt the integrity of the ELF files at execution, I will insert a parasite code to an ELF executable using Silvio Cesare’s algorithm [4], patching the entrypoint to a “fork() + portbind(31337) + auth(Password: n33tr0u5)” payload [5], which at the end has a jump to the original entrypoint:

As can be seen, the original binary (hostname) works perfectly after executing the parasite code (backdoor on port 31337). Now, let’s see what happens after patching it:

It worked perfectly and evidently it cannot be loaded by gdb !

In conclusion, the debuggers have certain parsing tasks and are software too, therefore they are also prone to bugs and security flaws. Debugging tools shouldn’t blindly trust in the data input supplied, in this case, the metadata of an ELF executable file. Always perform bound checking before trying to access invalid memory areas that might crash our applications.

Thanks for reading.

Alejandro.

Tools

– gdb (GNU debugger) <= 7.5.1 (crash due a NULL pointer dereference)

ELF anti-debugging/reversing patcher

– IDA Pro 6.3 (crash due an internal error)

ELF anti-debugging/reversing patcher

References

[1] Reverse Engineering under Linux by Diego Bauche Madero

[2] Abusing .CTORS and .DTORS for fun ‘n profit by Itzik Kotler

[3] DWARF

[4] UNIX Viruses by Silvio Cesare

[5] ELF_data_infector.c by Alejandro Hernández