This blog post contains a small portion of the entire analysis. Please refer to the white paper for full details to the research.

Disclaimer

Most of the testing was performed using paper money (demo accounts) provided online by the brokerage houses. Only a few accounts were funded with real money for testing purposes. In the case of commercial platforms, the free trials provided by the brokers were used. Only end-user applications and their direct servers were analyzed. Other backend protocols and related technologies used in exchanges and financial institutions were not tested.

This research is not about High Frequency Trading (HFT), blockchain, or how to get rich overnight.

Introduction

The days of open outcry on trading floors of the NYSE, NASDAQ, and other stock exchanges around the globe are gone. With the advent of electronic trading platforms and networks, the exchange of financial securities now is easier and faster than ever; but this comes with inherent risks.

The valuable information as well as the attack surface and vectors in trading environments are slightly different than those in banking systems.

Brokerage houses offer trading platforms to operate in the market. These applications allow you to do things including, but not limited to:

- Fund your account via bank transfers or credit card

- Keep track of your available equity and buying power (cash and margin balances)

- Monitor your positions (securities you own) and their performance (profit)

- Monitor instruments or indexes

- Send buy/sell orders

- Create alerts or triggers to be executed when certain thresholds are reached

- Receive real-time news or video broadcasts

- Stay in touch with the trading community through social media and chats

Needless to say, every single item on the previous list must be kept secret and only known by and shown to its owner.

Scope

My analysis started mid-2017 and concluded in July 2018. It encompassed the following platforms; many of them are some of the most used and well-known trading platforms, and some allow cryptocurrency trading:

- 16 Desktop applications

- 34 Mobile apps

- 30 Websites

These platforms are part of the trading solutions provided by the following brokers, which are used by tens of millions of traders. Some brokers offer the three types of platforms, however, in some cases only one or two were reviewed due to certain limitations:

- Ally Financial

- AvaTrade

- Binance

- Bitfinex

- Bitso

- Bittrex

- Bloomberg

- Capital One

- Charles Schwab

- Coinbase

- easyMarkets

- eSignal

- ETNA

- eToro

- E-TRADE

- ETX Capital

- ExpertOption

- Fidelity

- Firstrade

- FxPro

- GBMhomebroker

- Grupo BMV

- IC Markets

- Interactive Brokers

- IQ Option

- Kraken

- com

- Merrill Edge

- MetaTrader

- Net

- NinjaTrader

- OANDA

- Personal Capital

- Plus500

- Poloniex

- Robinhood

- Scottrade

- TD Ameritrade

- TradeStation

- Yahoo! Finance

Devices used:

- Windows 7 (64-bit)

- Windows 10 Home Single (64-bit)

- iOS 10.3.3 (iPhone 6) [not jailbroken]

- iOS 10.4 (iPhone 6) [not jailbroken]

- Android 7.1.1 (Emulator) [rooted]

Basic security controls/features were reviewed that represent just the tip of the iceberg when compared to more exhaustive lists of security checks per platform.

Results

Unfortunately, the results proved to be much worse compared with applications in retail banking. For example, mobile apps for trading are less secure than the personal banking apps reviewed in 2013 and 2015.

Apparently, cybersecurity has not been on the radar of the Financial Services Tech space in charge of developing trading apps. Security researchers have disregarded these technologies as well, probably because of a lack of understanding of money markets.

While testing I noted a basic correlation: the biggest brokers are the ones that invest more in fintech cybersecurity. Their products are more mature in terms of functionality, usability, and security.

Based on my testing results and opinion, the following trading platforms are the most secure:

| Broker | Platforms |

| TD Ameritrade | Web and mobile |

| Charles Schwab | Web and mobile |

| Merrill Edge | Web and mobile |

| MetaTrader 4/5 | Desktop and mobile |

| Yahoo! Finance | Web and mobile |

| Robinhood | Web and mobile |

| Bloomberg | Mobile |

| TradeStation | Mobile |

| Capital One | Mobile |

| FxPro cTrader | Desktop |

| IC Markets cTrader | Desktop |

| Ally Financial | Web |

| Personal Capital | Web |

| Bitfinex | Web and mobile |

| Coinbase | Web and mobile |

| Bitso | Web and mobile |

The medium- to high-risk vulnerabilities found on the different platforms include full or partial problems with encryption, Denial of Service, authentication, and/or session management problems. Despite the fact that these platforms implement good security features, they also have areas that should be addressed to improve their security.

Following the platforms I consider must improve in terms of security:

| Broker | Platforms |

| Interactive Brokers | Desktop, web and mobile |

| IQ Option | Desktop, web and mobile |

| AvaTrade | Desktop and mobile |

| E-TRADE | Web and mobile |

| eSignal | Desktop |

| TD Ameritrade’s Thinkorwim | Desktop |

| Charles Schwab | Desktop |

| TradeStation | Desktop |

| NinjaTrader | Desktop |

| Fidelity | Web |

| Firstrade | Web |

| Plus500 | Web |

| Markets.com | Mobile |

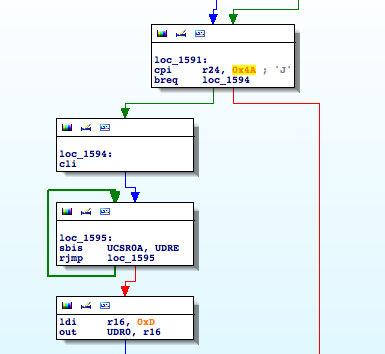

Unencrypted Communications

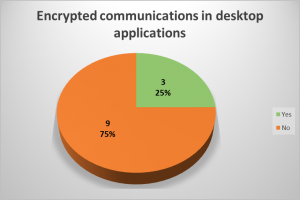

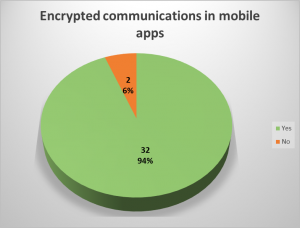

In 9 desktop applications (64%) and in 2 mobile apps (6%), transmitted data unencrypted was observed. Most applications transmit most of the sensitive data in an encrypted way, however, there were some cases where cleartext data could be seen in unencrypted requests.

Among the data seen unencrypted are passwords, balances, portfolio, personal information and other trading-related data. In most cases of unencrypted transmissions, HTTP in plaintext was seen, and in others, old proprietary protocols or other financial protocols such as FIX were used.

Under certain circumstances, an attacker with access to some part of the network, such as the router in a public WiFi, could see and modify information transmitted to and from the trading application. In the trading context, a malicious actor could intercept and alter values, such as the bid or ask prices of an instrument, and cause a user to buy or sell securities based on misleading information.

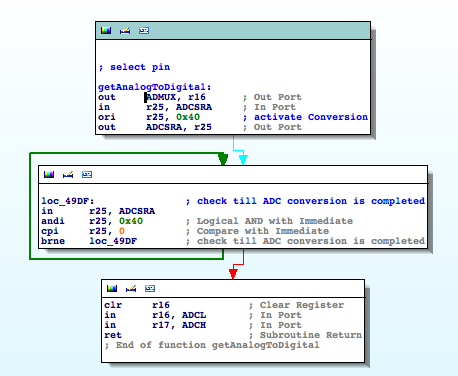

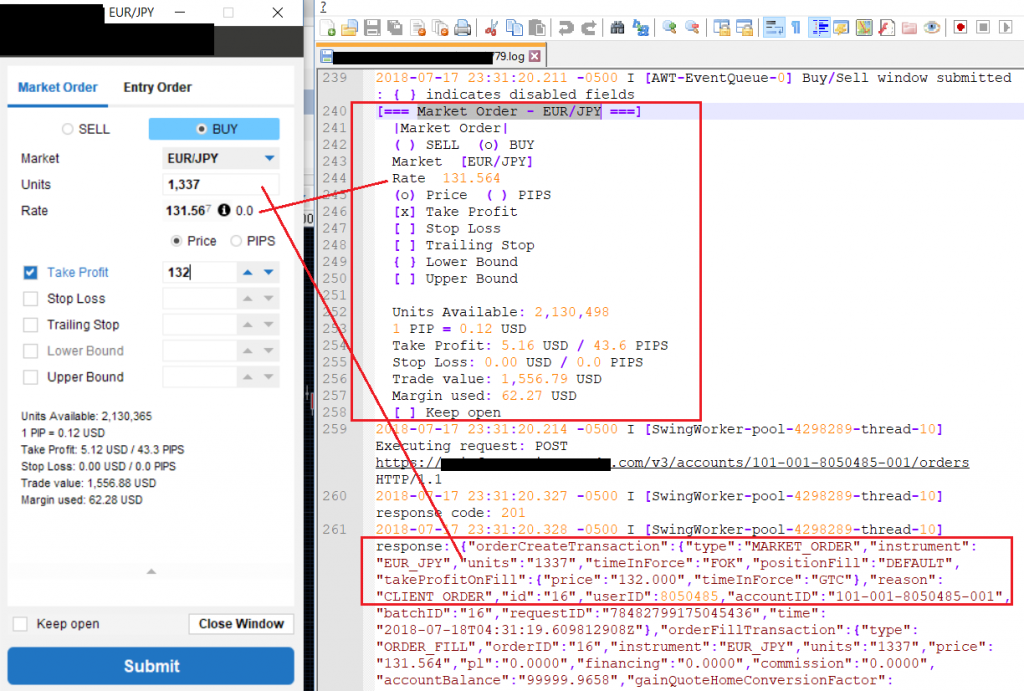

For example, the follow application uses unencrypted HTTP. In the screenshot, a buy order:

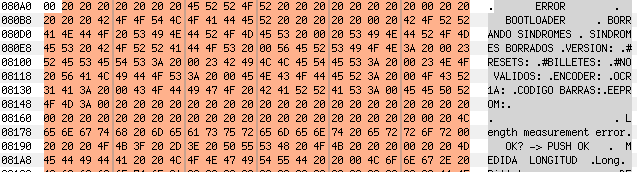

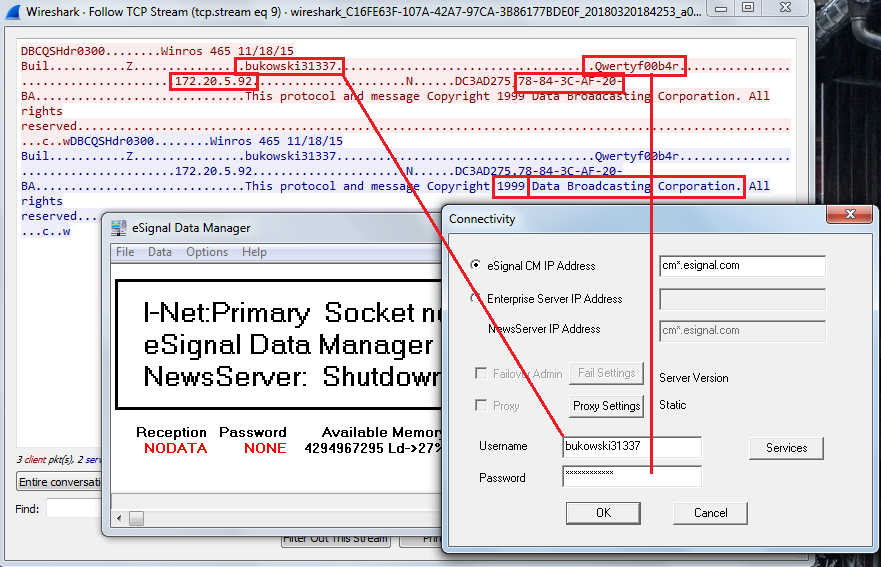

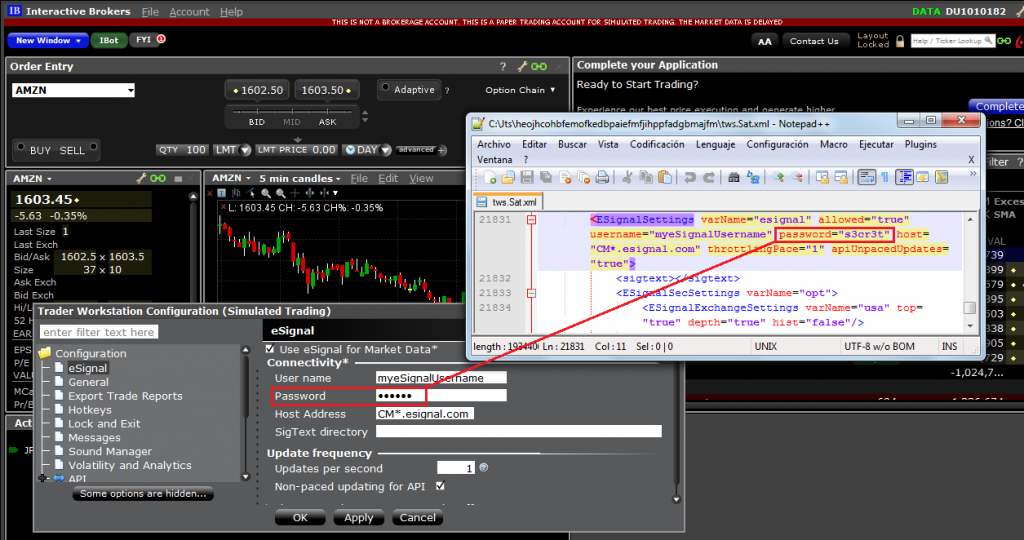

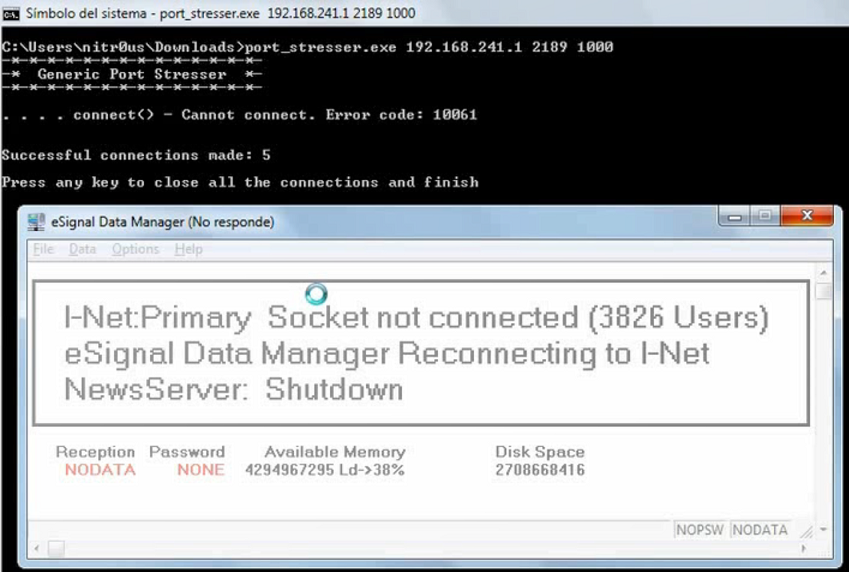

Another interesting example was found in eSignal’s Data Manager. eSignal is a known signal provider and integrates with a wide variety of trading platforms. It acts as a source of market data. During the testing, it was noted that Data Manager authenticates over an unencrypted protocol on the TCP port 2189, apparently developed in 1999.

As can be seen, the copyright states it was developed in 1999 by Data Broadcasting Corporation. Doing a quick search, we found a document from the SEC that states the company changed its name to Interactive Data Corporation, the owners of eSignal. In other words, it looks like it is an in-house development created almost 20 years ago. We could not corroborate this information, though.

The main eSignal login screen also authenticates through a cleartext channel:

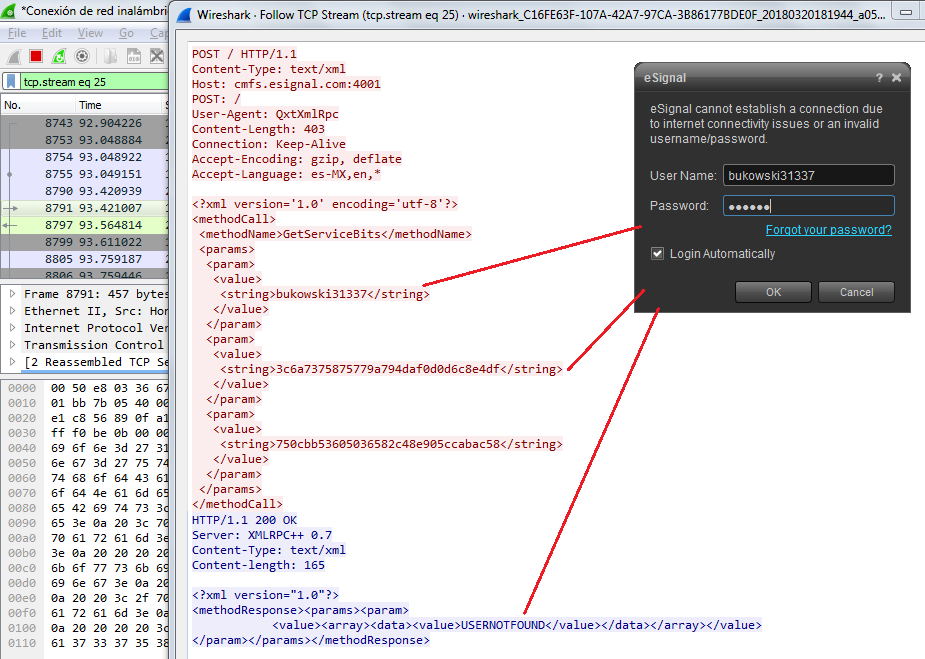

FIX is a protocol initiated in 1992 and is one of the industry standard protocols for messaging and trade execution. Currently, it is used by a majority of exchanges and traders. There are guidelines on how to implement it through a secure channel, however, the binary version in cleartext was mostly seen. Tests against the protocol itself were not performed in this analysis.

A broker that supports FIX:

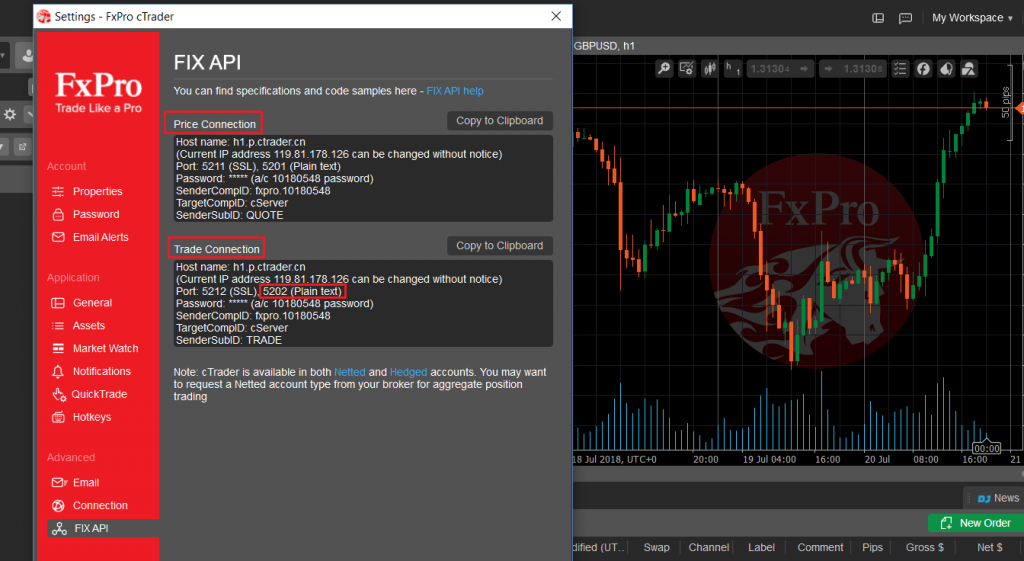

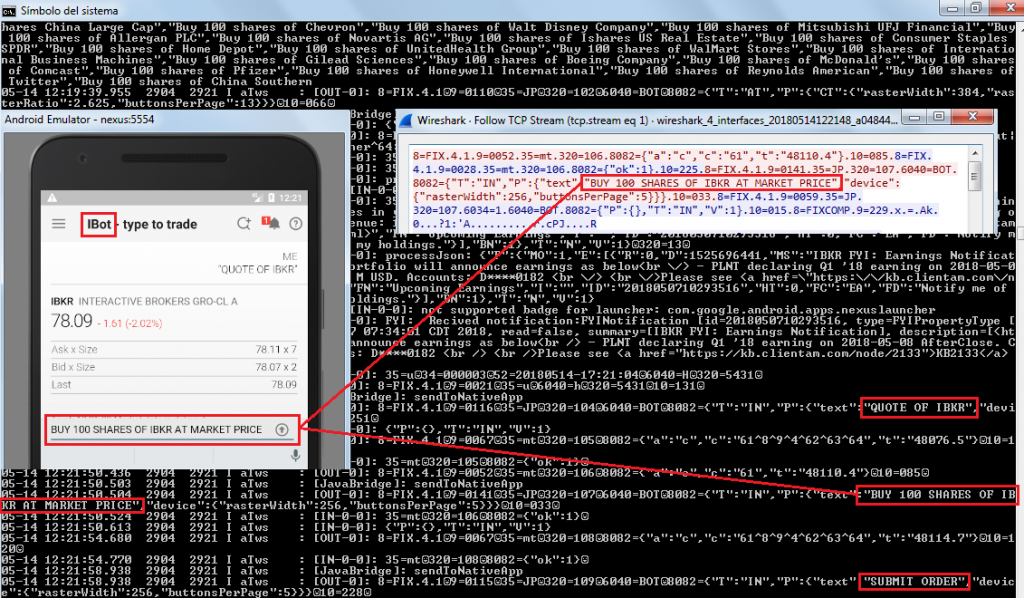

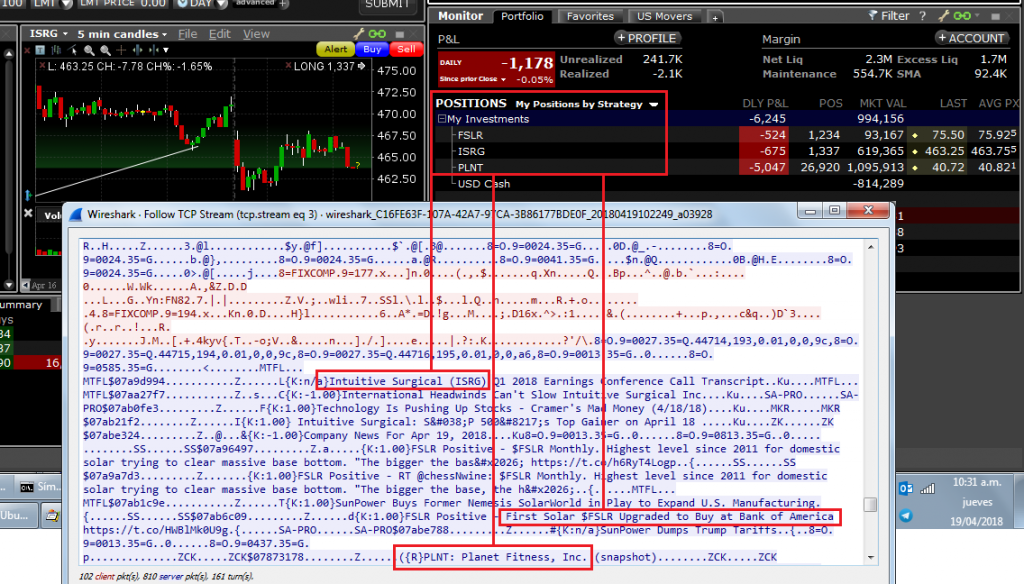

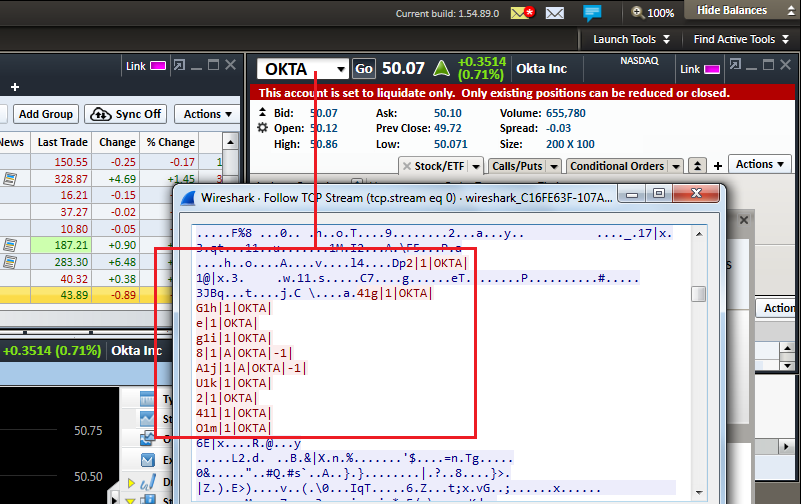

There are some cases where the application encrypts the communication channel, except in certain features. For instance, Interactive Brokers desktop and mobile applications encrypt all the communication, but not that used by iBot, the robot assistant that receives text or voice commands, which sends the instructions to the server embedded in a FIX protocol message in cleartext:

News related to the positions were also observed in plaintext:

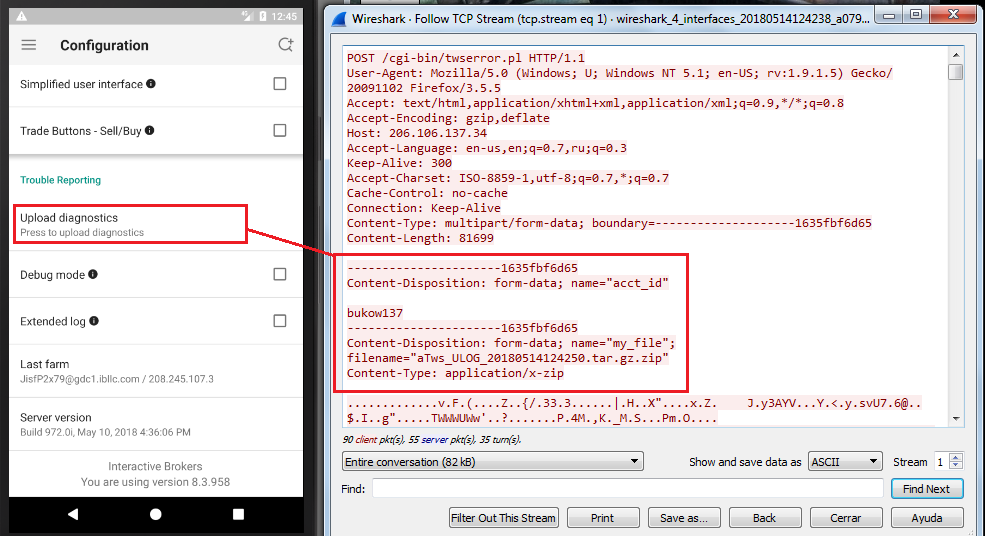

Another instance of an application that uses encryption but not for certain channels is this one, Interactive Brokers for Android, where a diagnostics log with sensitive data is sent to the server in a scheduled basis through unencrypted HTTP:

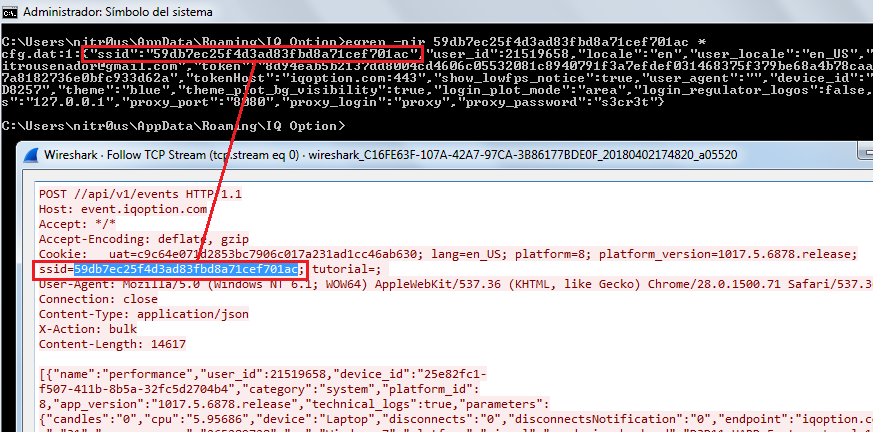

A similar platform that sends everything over HTTPS is IQ Option, but for some reason, it sends duplicate unencrypted HTTP requests to the server disclosing the session cookie.

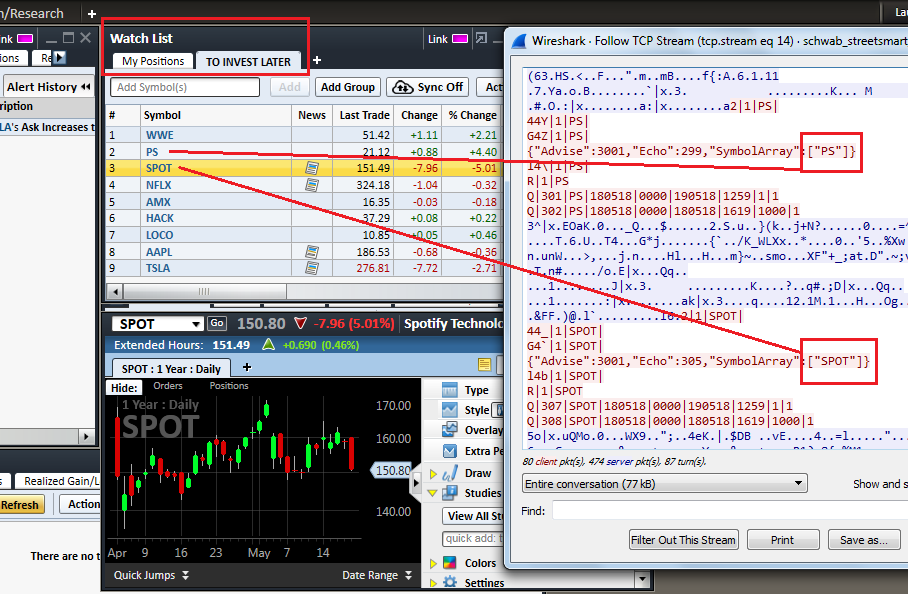

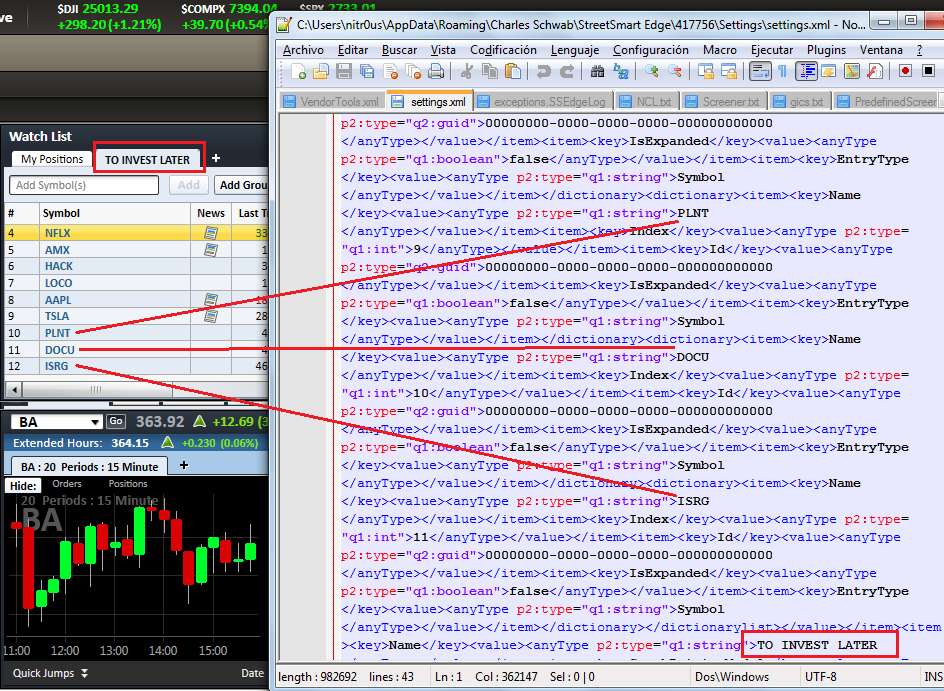

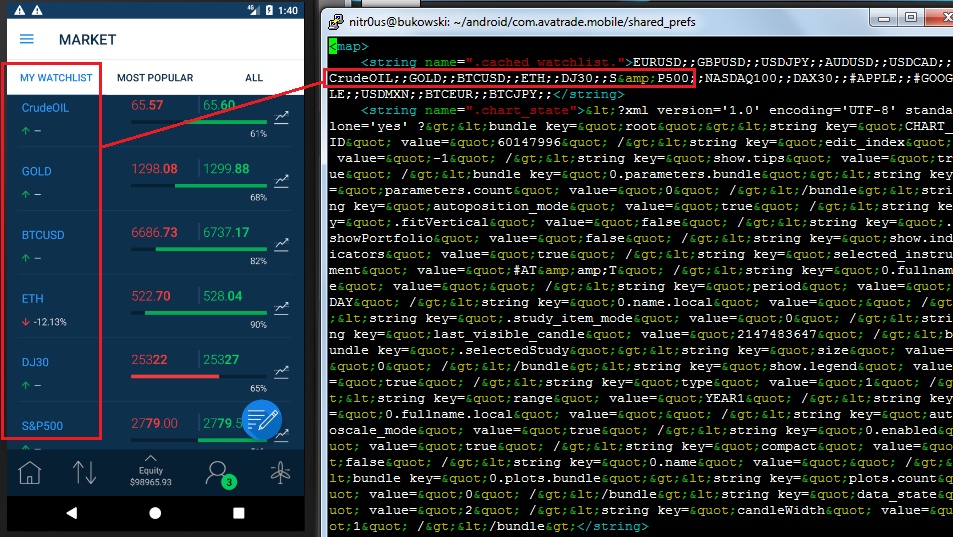

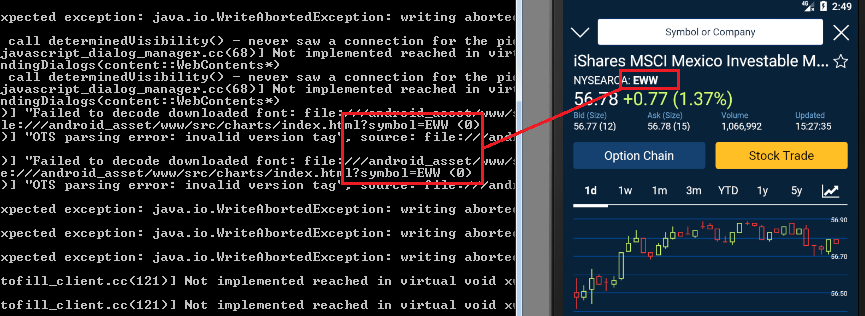

Others appear to implement their own binary protocols, such as Charles Schwab, however, symbols in watchlists or quoted symbols could be seen in cleartext:

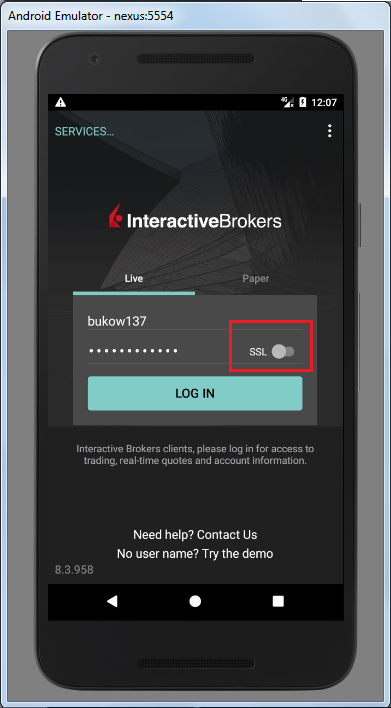

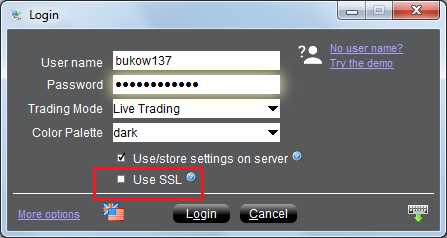

Interactive Brokers supports encryption but by default uses an insecure channel; an inexperienced user who does not know the meaning of “SSL” (Secure Socket Layer) won’t enable it on the login screen and some sensitive data will be sent and received without encryption:

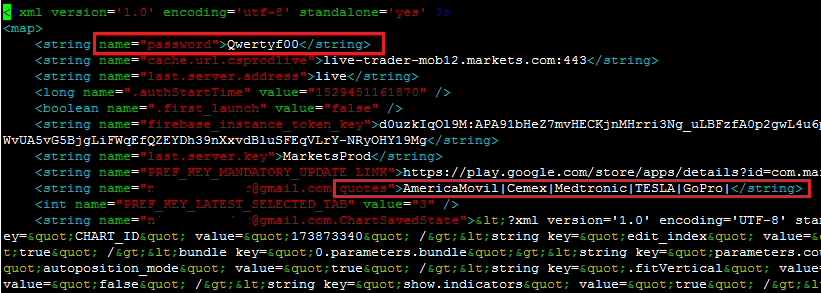

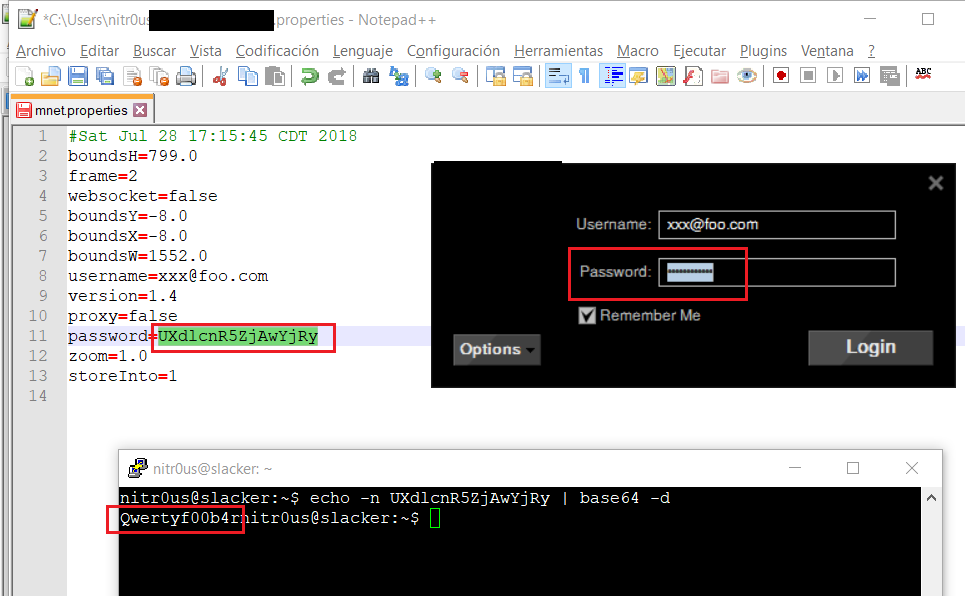

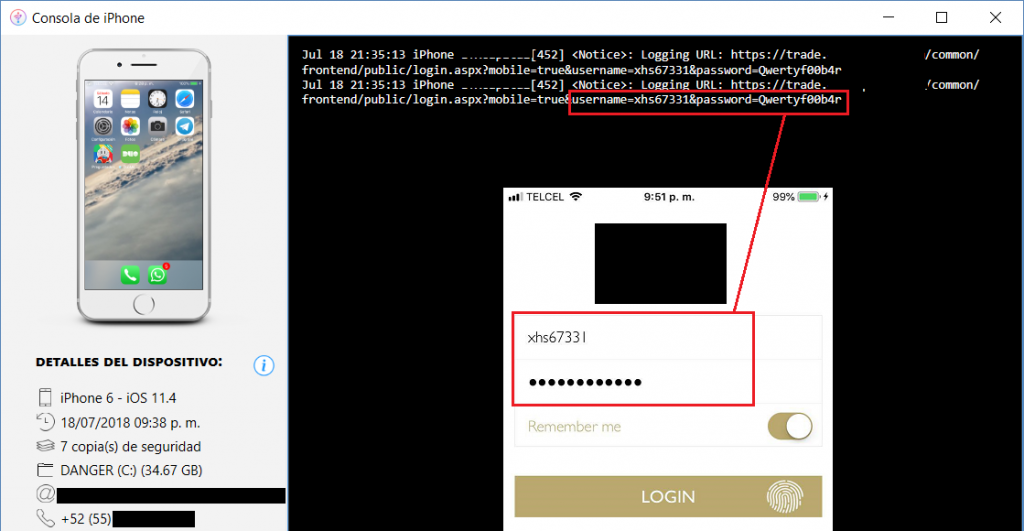

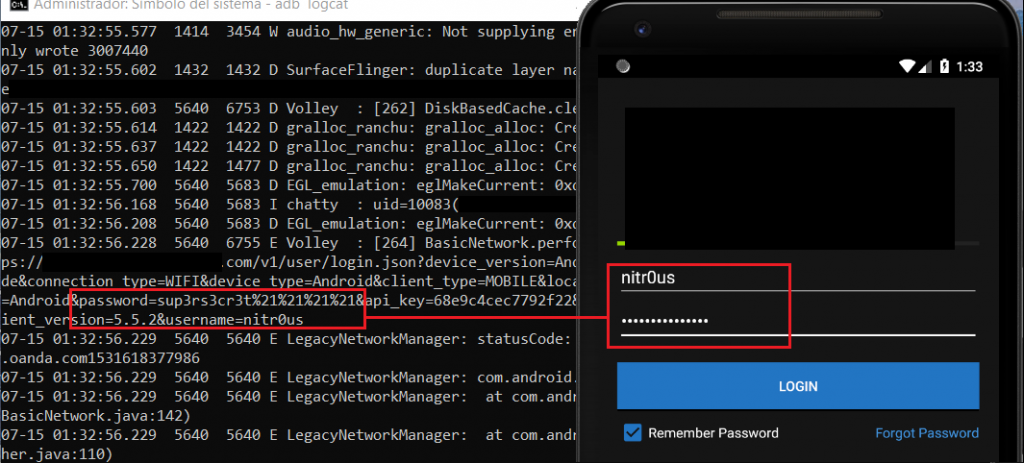

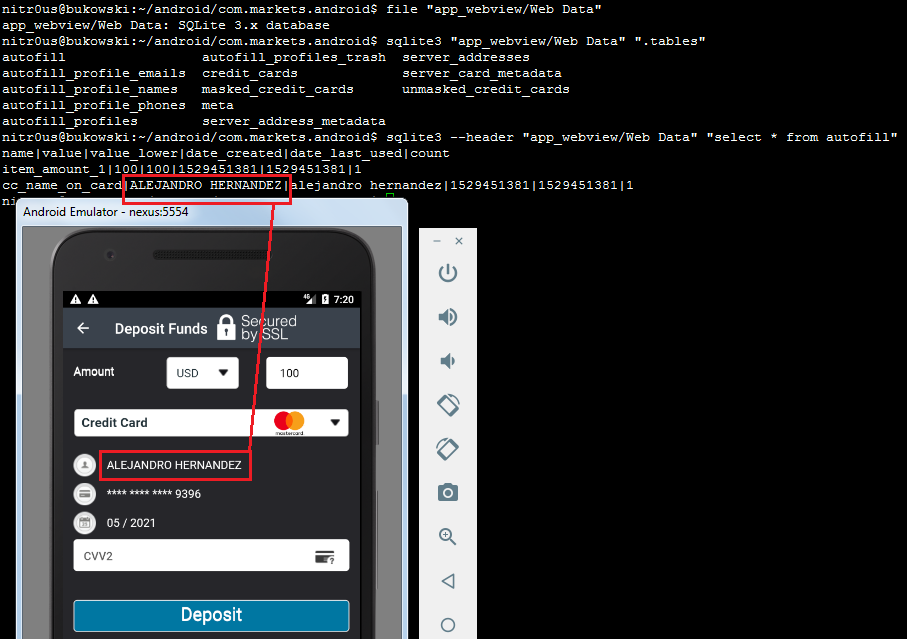

Passwords Stored Unencrypted

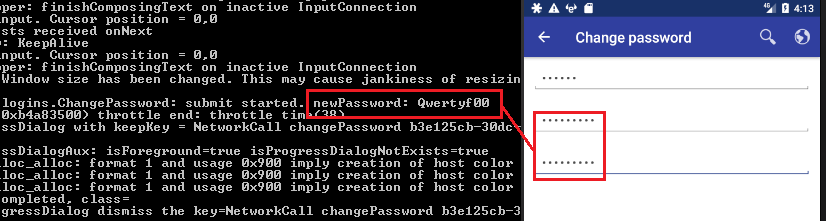

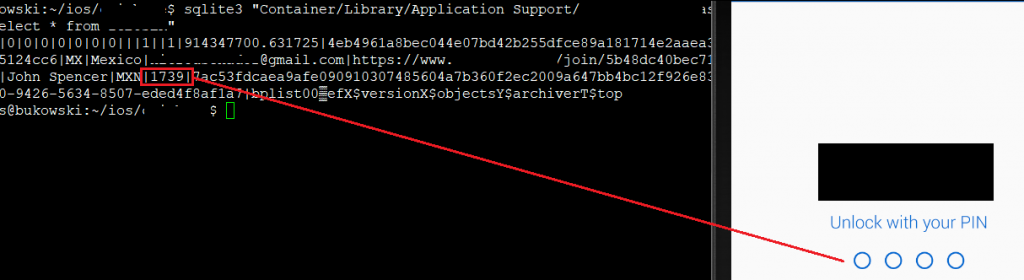

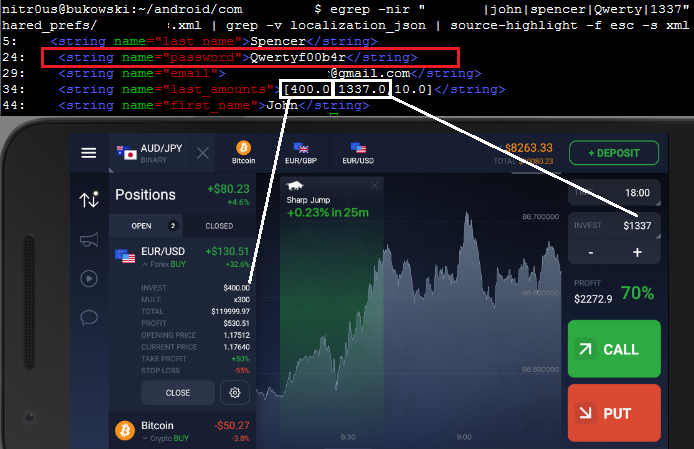

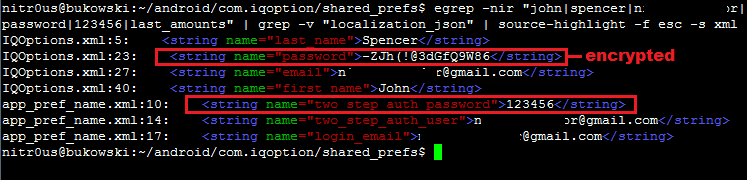

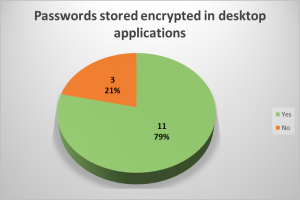

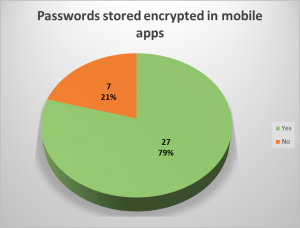

In 7 mobile apps (21%) and in 3 desktop applications (21%), the user’s password was stored unencrypted in a configuration file or sent to log files. Local access to the computer or mobile device is required to extract them, though. This access could be either physical or through malware.

In a hypothetical attack scenario, a malicious user could extract a password from the file system or the logging functionality without any in-depth know-how (it’s relatively easily), log in through the web-based trading platform from the brokerage firm, and perform unauthorized actions. They could sell stocks, transfer the money to a newly added bank account, and delete this bank account after the transfer is complete. During testing, I noticed that most web platforms (+75%) support two-factor authentication (2FA), however, it’s not enabled by default, the user must go to the configuration and enable it to receive authorization codes by text messages or email. Hence, if 2FA is not enabled in the account, it’s possible for an attacker, that knows the password already, to link a new bank account and withdraw the money from sold securities.

The following are some instances where passwords are stored locally unencrypted or sent to logs in cleartext:

Base64 is not encryption:

In some cases, the password was sent to the server as a GET parameter, which is also insecure:

One PIN for login and unlocking the app was also seen:

In IQ Option, the password was stored completely unencrypted:

However, in a newer version, the password is encrypted in a configuration file, but is still stored in cleartext in a different file:

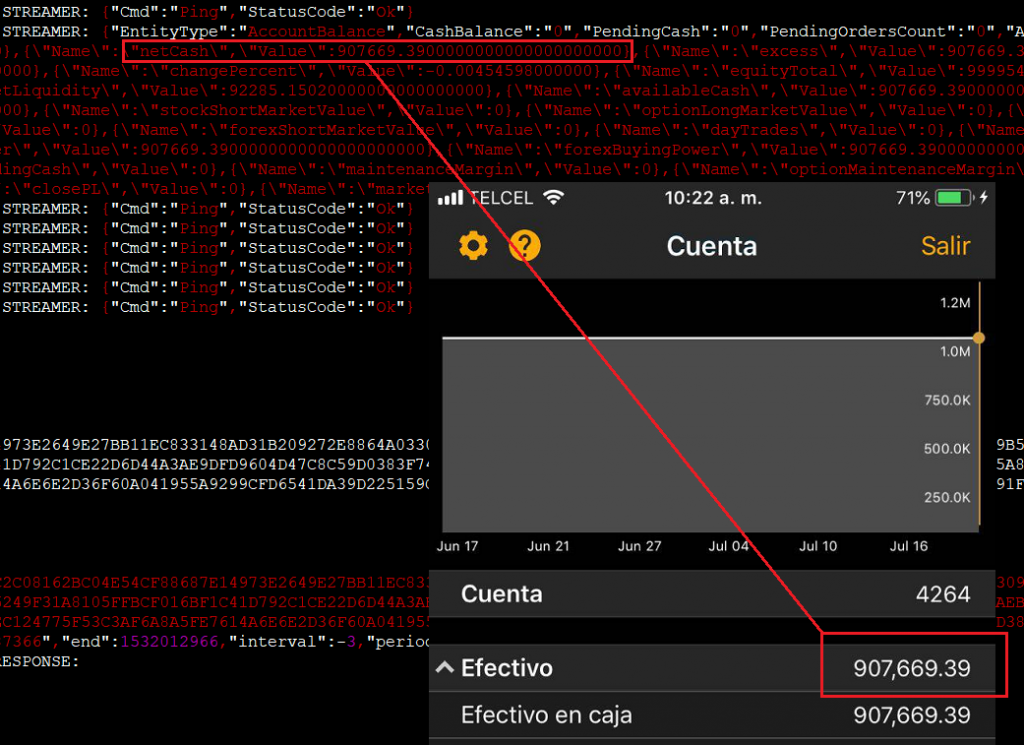

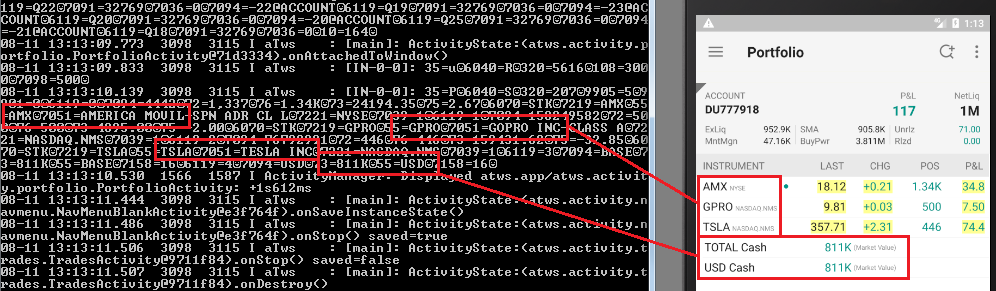

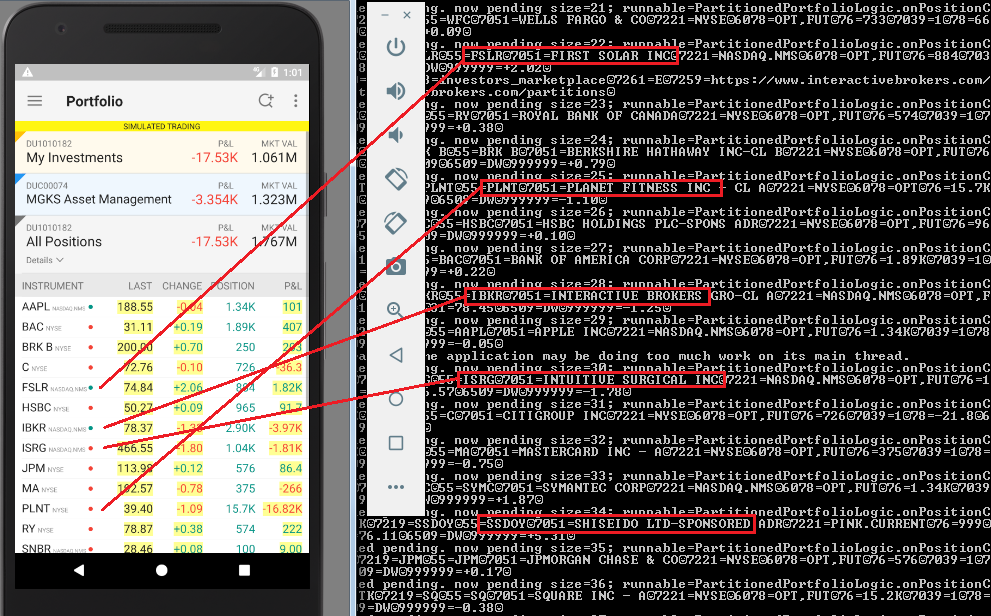

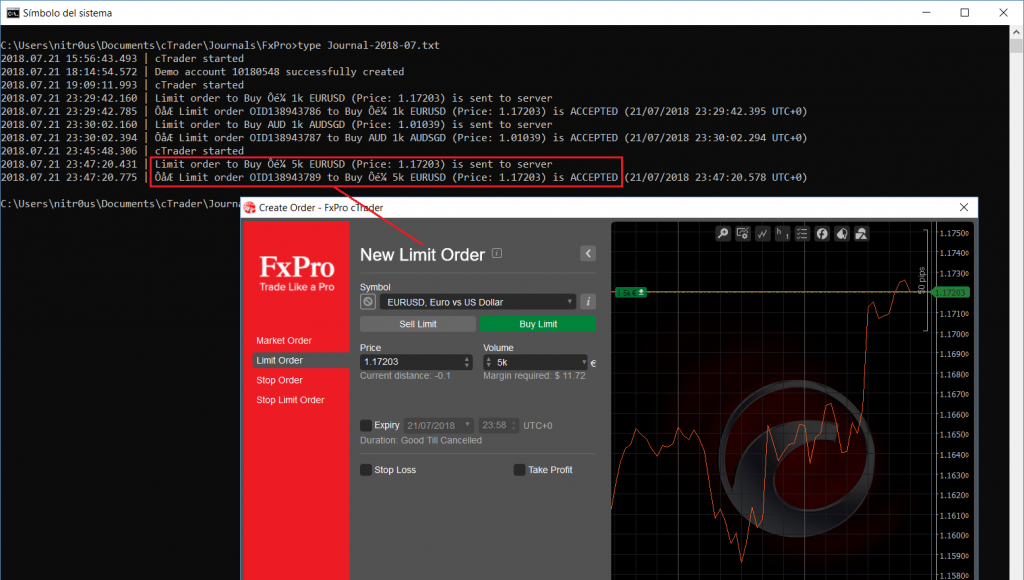

Trading and Account Information Stored Unencrypted

In the trading context, operational or strategic data must not be stored unencrypted nor sent to the any log file in cleartext. This sensitive data encompasses values such as personal data, general balances, cash balance, margin balance, net worth, net liquidity, the number of positions, recently quoted symbols, watchlists, buy/sell orders, alerts, equity, buying power, and deposits. Additionally, sensitive technical values such as username, password, session ID, URLs, and cryptographic tokens should not be exposed either.

8 desktop applications (57%) and 15 mobile apps (44%) sent sensitive data in cleartext to log files or stored it unencrypted. Local access to the computer or mobile device is required to extract this data, though. This access could be either physical or through malware.

If these values are somehow leaked, a malicious user could gain insight into users’ net worth and investing strategy by knowing which instruments users have been looking for recently, as well as their balances, positions, watchlists, buying power, etc.

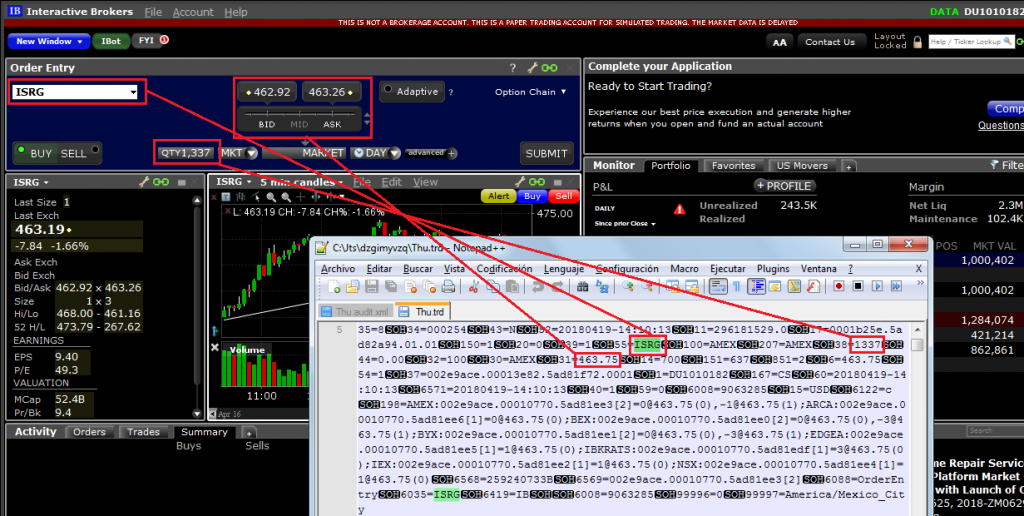

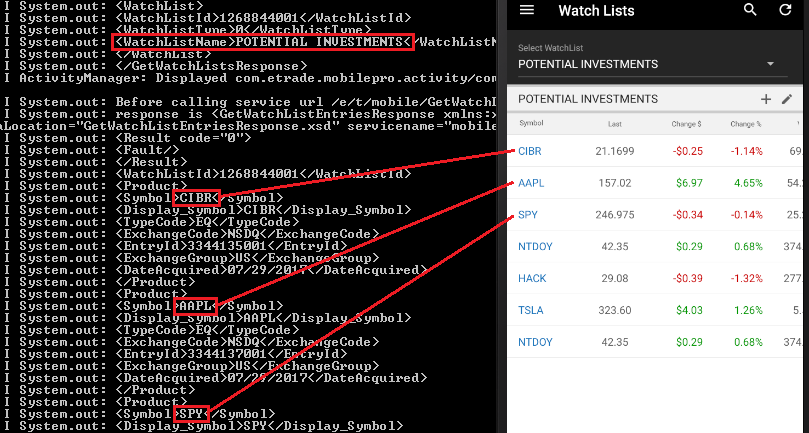

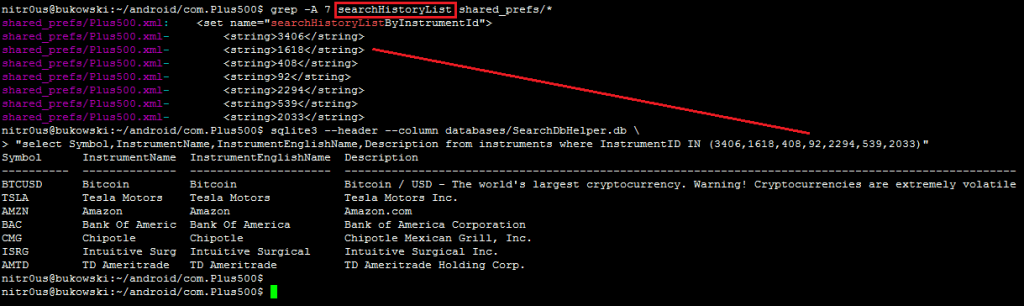

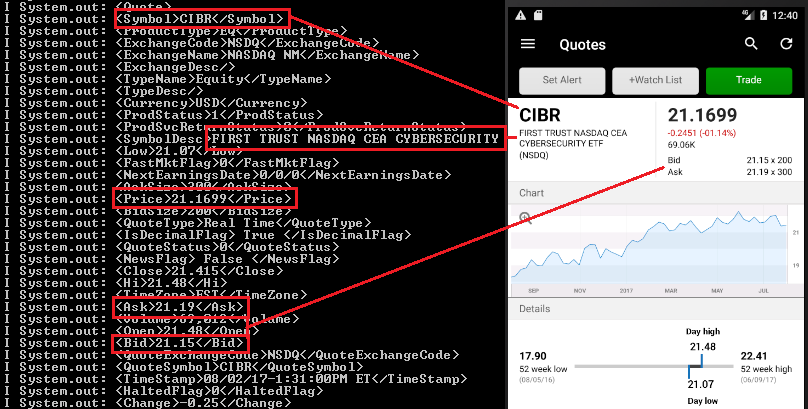

The following screenshots show applications that store sensitive data unencrypted:

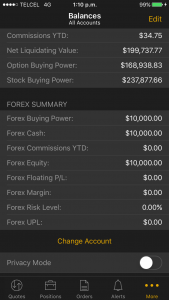

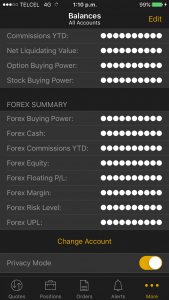

Balances:

Investment portfolio:

Buy/sell orders:

Watchlists:

Recently quoted symbols:

Other data:

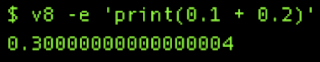

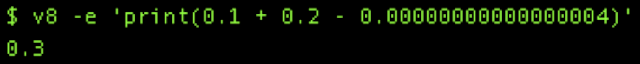

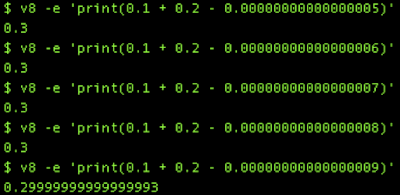

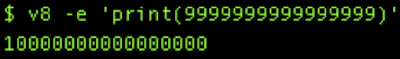

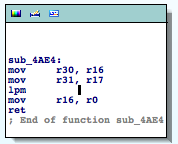

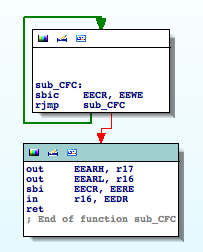

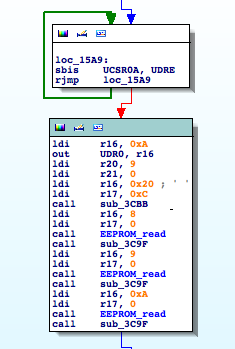

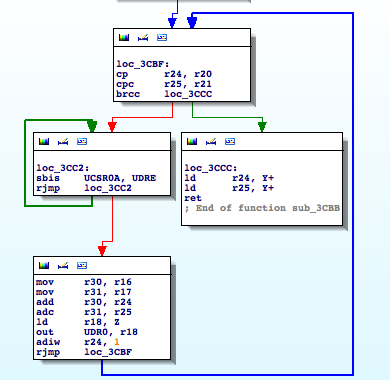

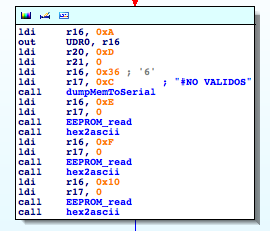

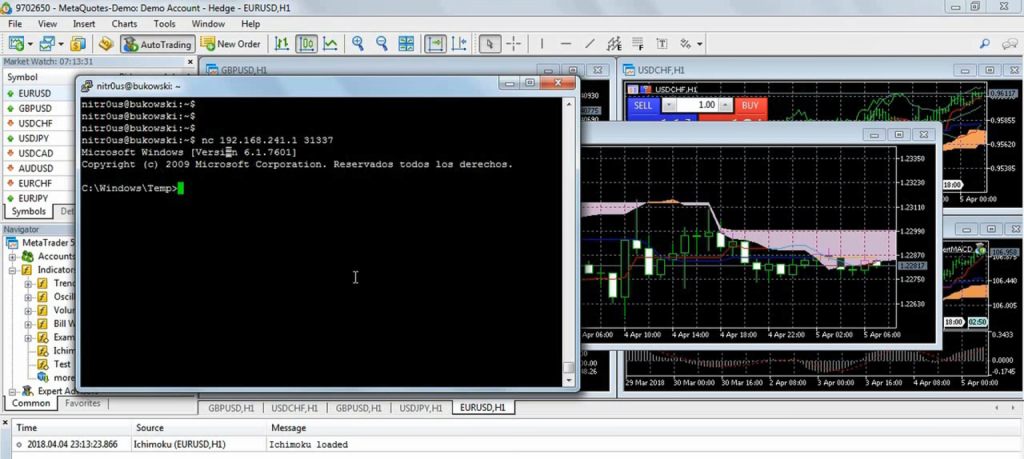

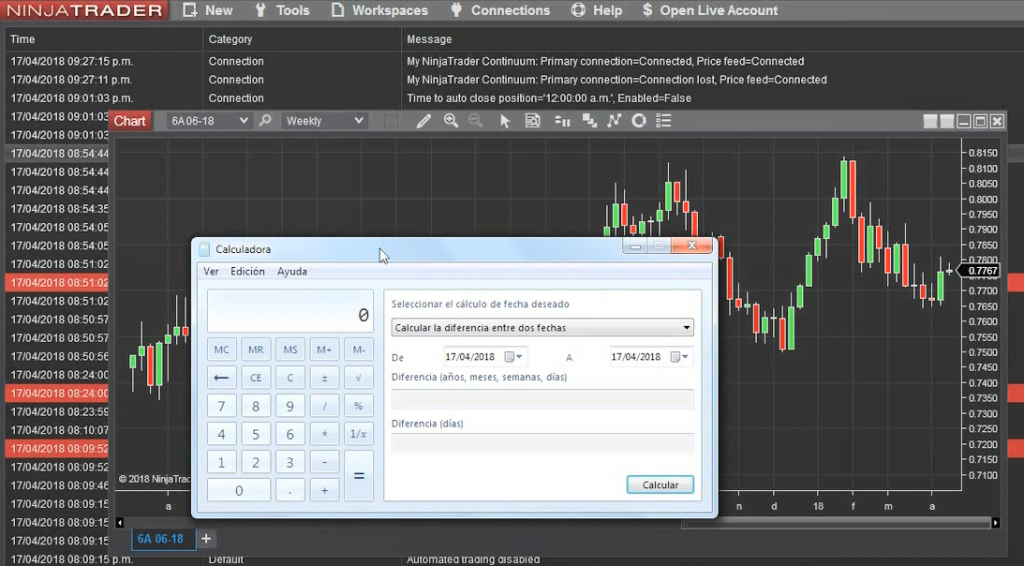

Trading Programming Languages with DLL Import Capabilities

This is not a bug, it’s a feature. Some trading platforms allow their customers to create their own automated trading robots (a.k.a. expert advisors), indicators, and other plugins. This is achieved through their own programming languages, which in turn are based on other languages, such as C++, C#, or Pascal.

The following are a few of the trading platforms with their own trading language:

- MetaTrader: MetaQuotes Language (Based on C++ – Supports DLL imports)

- NinjaTrader: NinjaScript (Based on C# – Supports DLL imports)

- TradeStation: EasyLanguage (Based on Pascal – Supports DLL imports)

- AvaTraceAct: ActFX (Based on Pascal – Does not support OS commands nor DLL imports)

- (FxPro/IC Markets) cTrader: Based on C# (OS command and DLL support is unknown)

Nevertheless, some platforms such as MetaTrader warn their customers about the dangers related to DLL imports and advise them to only execute plugins from trusted sources. However, there are Internet tutorials claiming, “to make you rich overnight” with certain trading robots they provide. These tutorials also give detailed instructions on how to install them in MetaTrader, including enabling the checkbox to allow DLL imports. Innocent non-tech savvy traders are likely to enable such controls, since not everyone knows what a DLL file is or what is being imported from it. Dangerous.

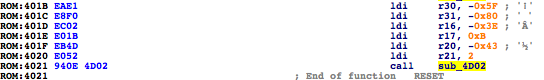

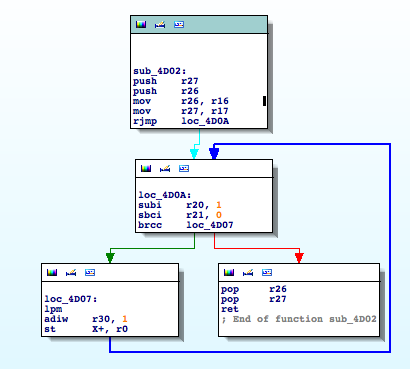

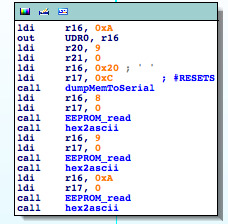

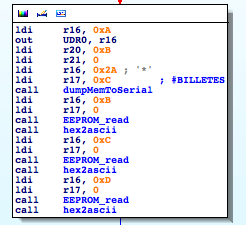

Following a malicious Ichimoku indicator that, when loaded into any chart, downloads and executes a backdoor for remote access:

Another basic example is NinjaTrader, which simply allows OS commands through C#’s System.Diagnostics.Process.Start(). In the following screenshot, calc.exe executed from the chart initialization routine:

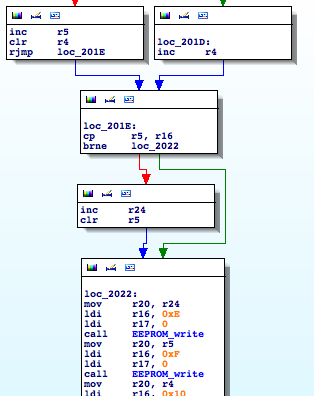

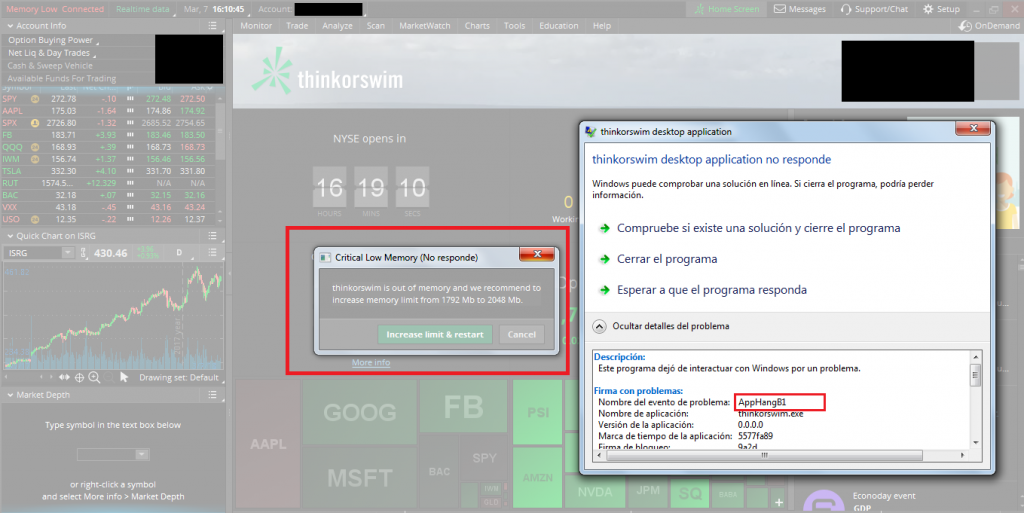

Denial of Service

Many desktop platforms integrate with other trading software through common TCP/IP sockets. Nevertheless, some common weaknesses are present in the connections handling of such services.

A common error is not implementing a limit of the number of concurrent connections. If there is no limit of concurrent connections on a TCP daemon, applications are susceptible to denial-of-service (DoS) or other type of attacks depending on the nature of the applications.

For example, TD Ameritrade’s Thinkorswim TCP-Orders Server listens on the TCP port 2000 in the localhost interface, and there is no limit for connections nor a waiting time between orders. This leads to the following problems:

- Memory leakage since, apparently, the resources assigned to every connection are not freed upon termination.

- Continuous order pop-ups (one pop-up per order received through the TCP server) render the application useless.

- A NULL pointer dereference is triggered and an error report (.zip file) is created.

Regardless, it listens on the local interface only. There are different ways to reach this port, such as XMLHttpRequest() in JavaScript through a web browser.

Memory leakage could be easily triggered by creating as many connections as possible:

A similar DoS vulnerability due to memory exhaustion was found in eSignal’s Data Manager. eSignal is a known signal provider and integrates with a wide variety of trading platforms. It acts as a source of market data; therefore, availability is the most important asset:

It’s recommended to implement a configuration item to allow the user to control the behavior of the TCP order server, such as controlling the maximum number of orders sent per minute as well as the number of seconds to wait between orders to avoid bottlenecks.

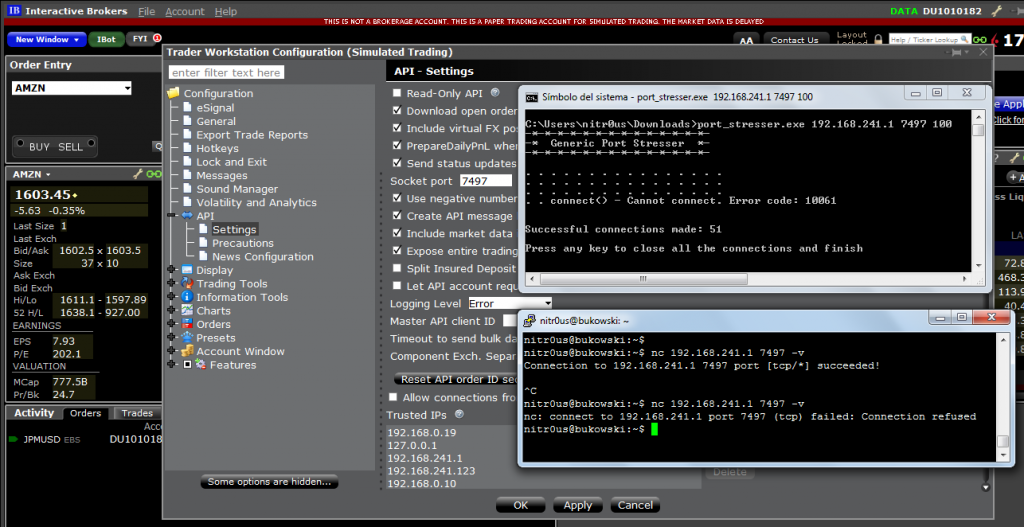

The following capture from Interactive Brokers shows when this countermeasure is implemented properly. No more than 51 users can be connected simultaneously:

Session Still Valid After Logout

Normally, when the logout button is pressed in an app, the session is finished on both sides: server and client. Usually the server deletes the session token from its valid session list and sends a new empty or random value back to the client to clear or overwrite the session token, so the client needs to reauthenticate next time.

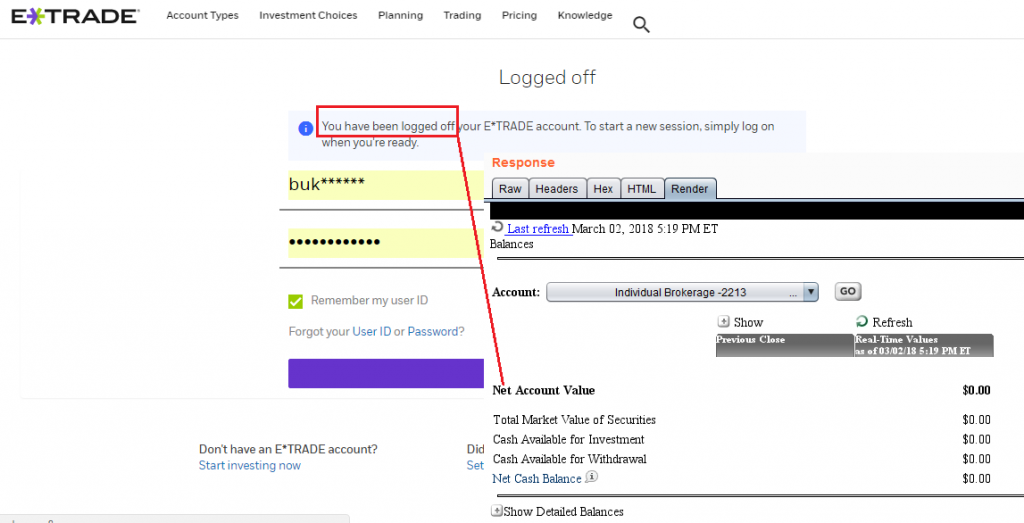

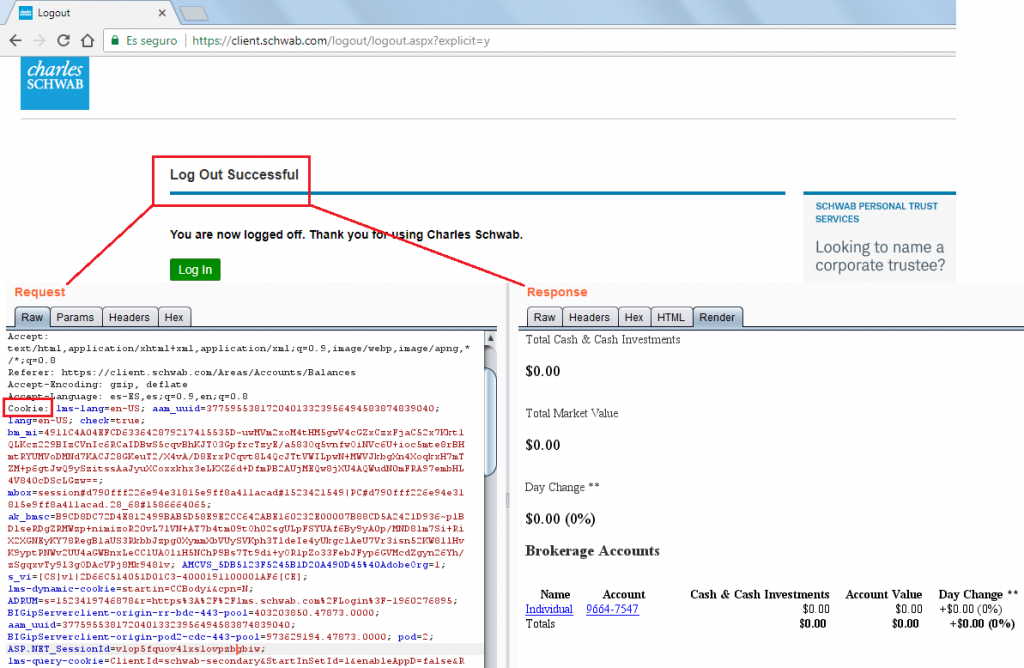

In some web platforms such as E-TRADE, Charles Schwab, Fidelity and Yahoo! Finance (Fixed), the session was still valid one hour after clicking the logout button:

Authentication

While most web-based trading platforms support 2FA (+75%), most desktop applications do not implement it to authenticate their users, even when the web-based platform from the same broker supports it.

Nowadays, most modern smartphones support fingerprint-reading, and most trading apps use it to authenticate their customers. Only 8 apps (24%) do not implement this feature.

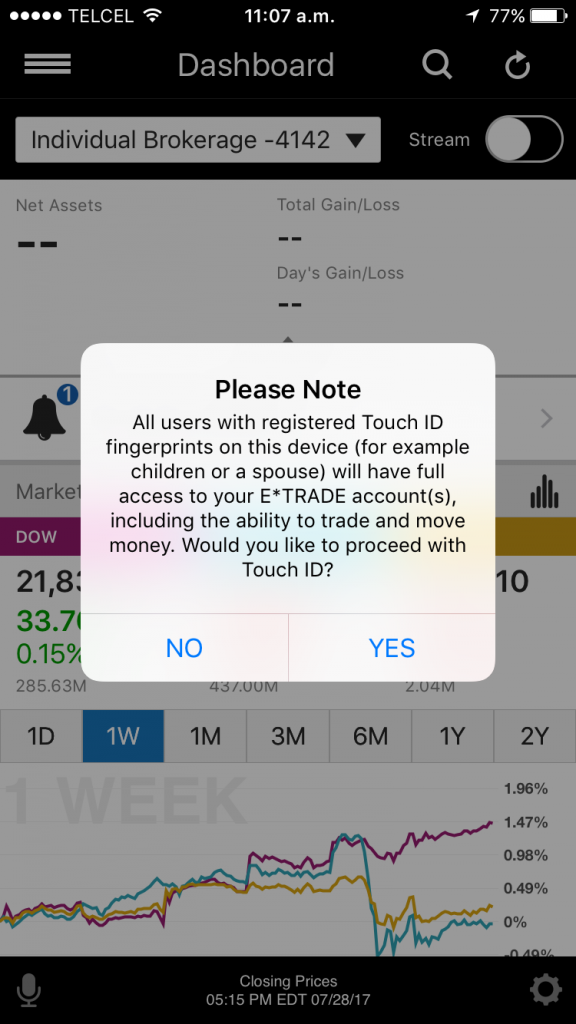

Unfortunately, using the fingerprint database in the phone has a downside:

Weak Password Policies

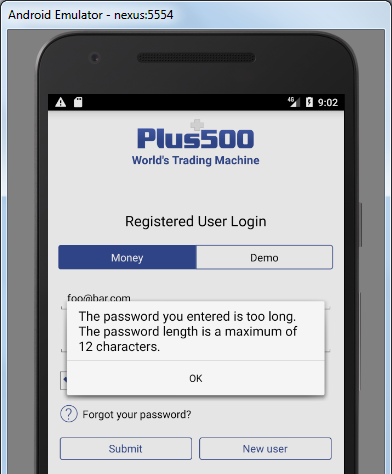

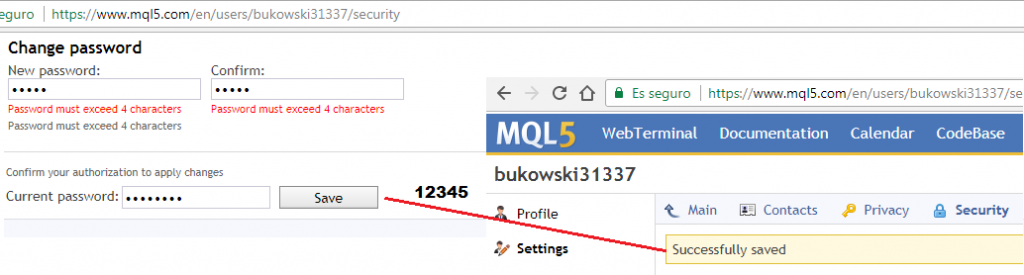

Some institutions let the users choose easily guessable passwords. For example:

The lack of a secure password policy increases the chances that a brute-force attack will succeed in compromising user accounts.

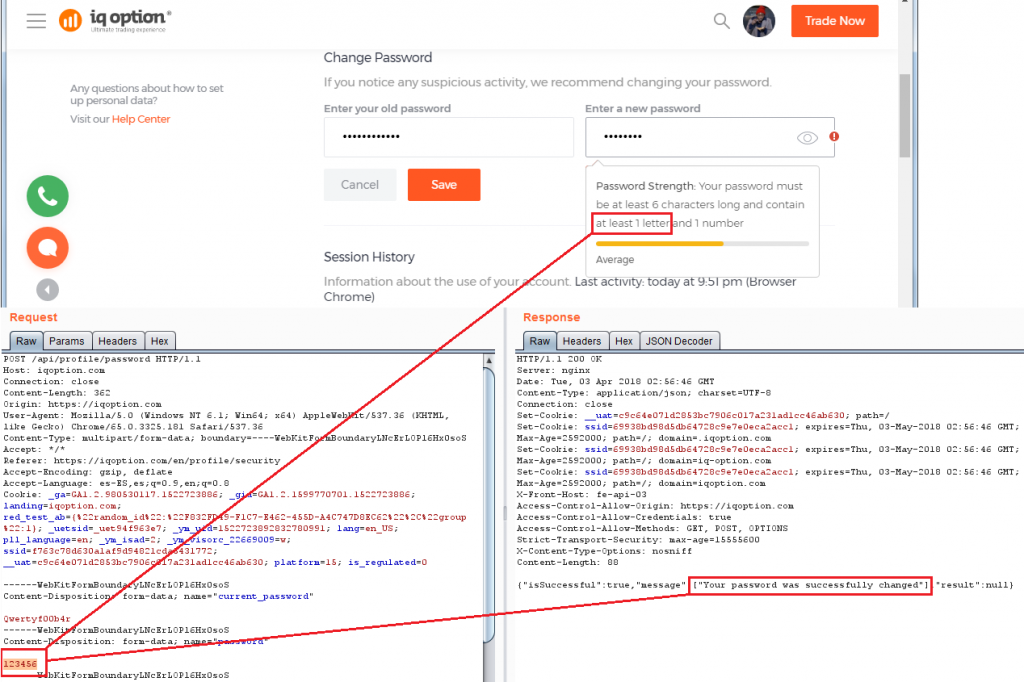

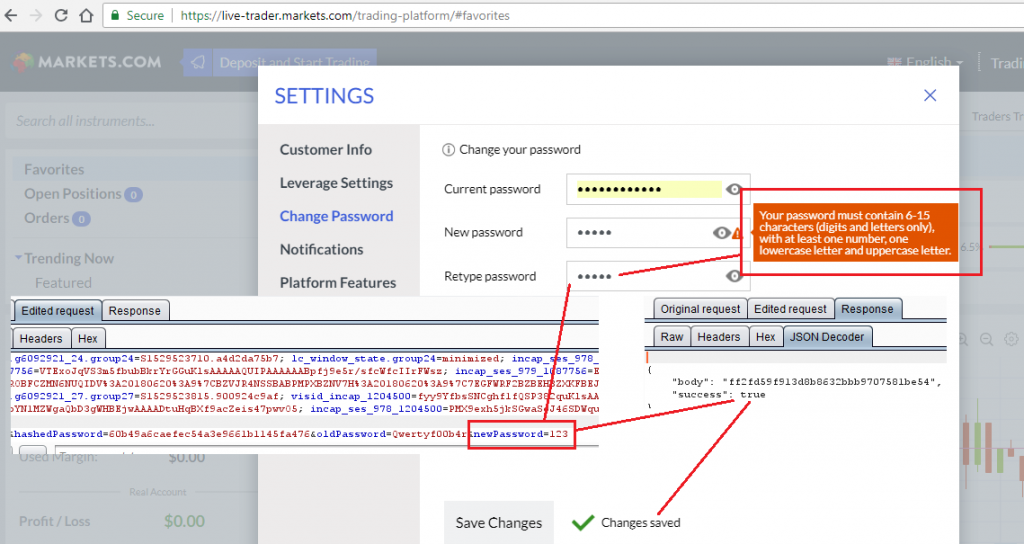

In some cases, such as in IQ Option and Markets.com, the password policy validation is implemented on the client-side only, hence, it is possible to intercept a request and send a weak password to the server:

Automatic Logout/Lockout for Idle Sessions

Most web-based platforms logout/lockout the user automatically, but this is not the case for desktop (43%) and mobile apps (25%). This is a security control that forces the user to authenticate again after a period of idle time.

Privacy Mode

This mode protects the customers’ private information from being displayed on the screen in public areas where shoulder-surfing attacks are feasible. Most of the mobile apps, desktop applications, and web platforms do not implement this useful and important feature.

The following images show before and after enabling privacy mode in Thinkorswim for mobile:

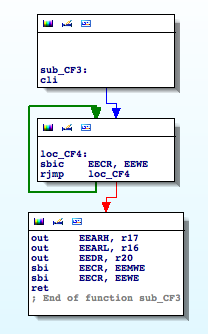

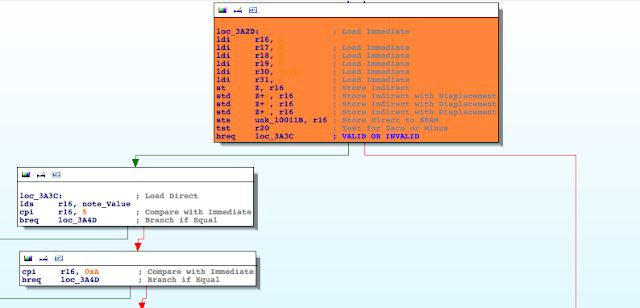

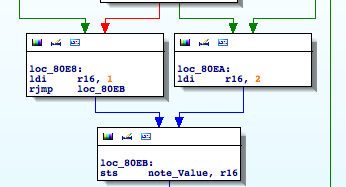

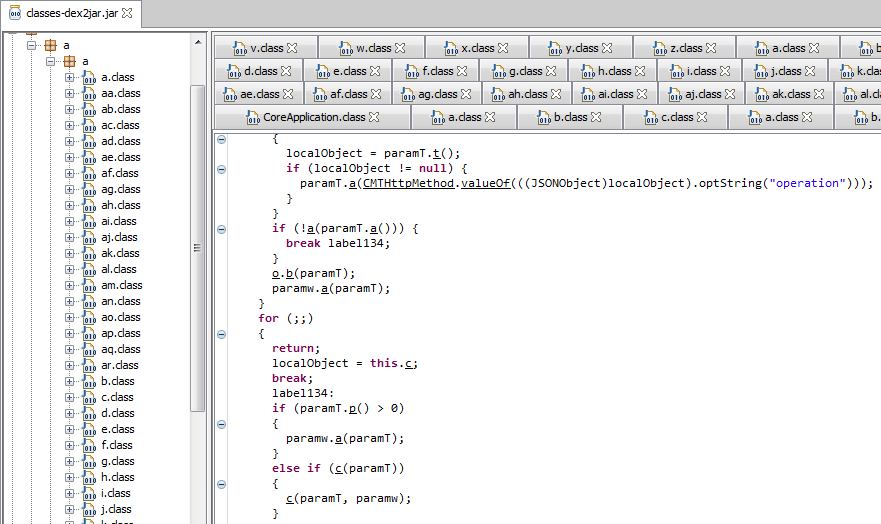

Hardcoded Secrets in Code and App Obfuscation

16 Android .apk installers (47%) were easily reverse engineered to human-readable code since they lack of obfuscation. Most Java and .NET-based desktop applications were also reverse-engineered easily. The rest of the applications had medium to high levels of obfuscation, such as Merrill Edge in the next screenshot.

The goal of obfuscation is to conceal the applications purpose (security through obscurity) and logic in order to deter reverse engineering and to make it more difficult.

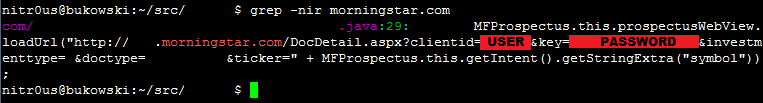

In the non-obfuscated platforms, there are hardcoded secrets such as cryptographic keys and third-party service partner passwords. This information could allow unauthorized access to other systems that are not under the control of the brokerage houses. For example, a Morningstar.com account (investment research) hardcoded in a Java class:

Interestingly, 14 of the mobile apps (41%) and 4 of the desktop platforms (29%) have traces (hostnames and IPs) about the internal development and testing environments where they were made or tested. Some hostnames are reachable from the Internet and since they’re testing systems they could lack of proper protections.

SSL Certificate Validation

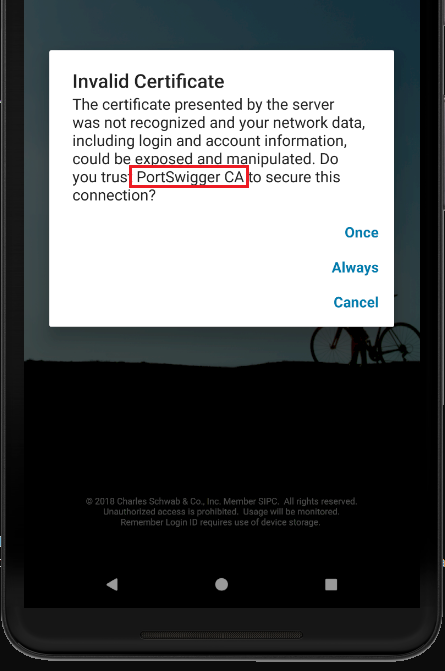

11 of the reviewed mobile apps (32%) do not check the authenticity of the remote endpoint by verifying its SSL certificate; therefore, it’s feasible to perform Man-in-the-Middle (MiTM) attacks to eavesdrop on and tamper with data. Some MiTM attacks require to trick the user into installing a malicious certificate on their phones, though.

The ones that verify the certificate normally do not transmit any data, however, only Charles Schwab allows the user to use the app with the provided certificate:

Lack of Anti-exploitation Mitigations

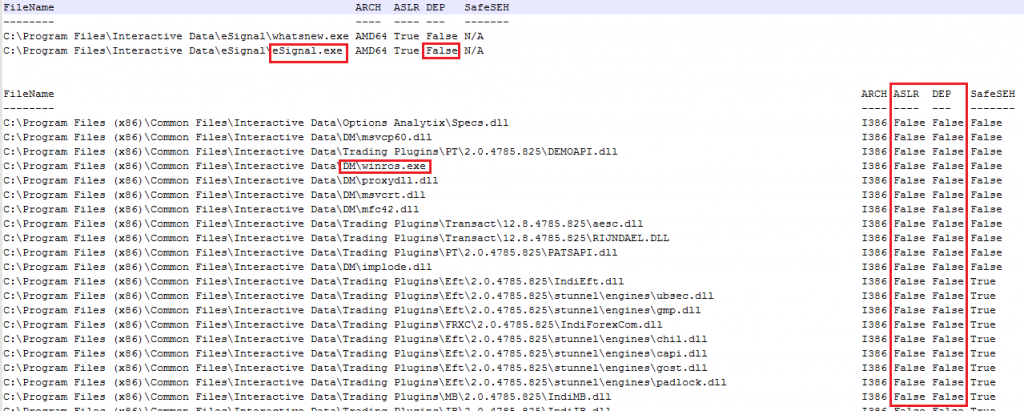

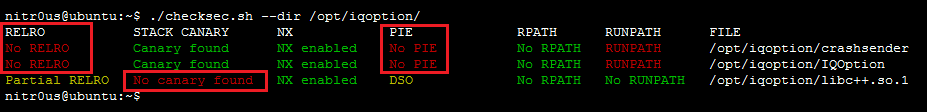

ASLR randomizes the virtual address space locations of dynamically loaded libraries. DEP disallows the execution of data in the data segment. Stack Canaries are used to identify if the stack has been corrupted. These security features make much more difficult for memory corruption bugs to be exploited and execute arbitrary code.

The majority of the desktop applications do not have these security features enabled in their final releases. In some cases, that these features are only enabled in some components, not the entire application. In other cases, components that handle network connections also lack these flags.

Linux applications have similar protections. IQ Option for Linux does not enforce all of them on certain binaries.

Other Weaknesses

More issues were found in the platforms. For more details, please refer to the white paper.

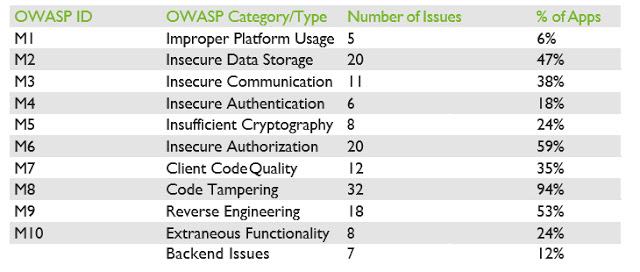

Statistics

Since a picture is worth a thousand words, consider the following graphs:

For more statistics, please refer to the white paper.

Responsible Disclosure

One of IOActive’s missions is to act responsibly when it comes to vulnerability disclosure. In September 2017 we sent a detailed report to 13 of the brokerage firms whose mobile trading apps presented some of the higher risks vulnerabilities discussed in this paper. More recently, between May and July 2018, we sent additional vulnerability reports to brokerage firms.

As of July 27, 2018, 19 brokers that have medium- or high-risk vulnerabilities in any of their platforms were contacted.

TD Ameritrade and Charles Schwab were the brokers that communicated more with IOActive for resolving the reported issues.

For a table with the current status of the responsible disclosure process, please refer to the white paper.

Conclusions and Recommendations

- Trading platforms are less secure than the applications seen in retail banking.

- There’s still a long way to go to improve the maturity level of security in trading technologies.

- End users should enable all the security mechanisms their platforms offer, such as 2FA and/or biometric authentication and automatic lockout/logout. Also, it’s recommended not to trade while connected to public networks and not to use the same password for other financial services.

- Brokerage firms should perform regular internal audits to continuously improve the security of their trading platforms.

- Brokerage firms should also offer security guidance in their online education centers.

- Developers should analyze their current applications to determine if they suffer from the vulnerabilities described in this paper, and if so, fix them.

- Developers should design new, more secure financial software following secure coding practices.

- Regulators should encourage brokers to implement safeguards for a better trading environment. They could also create trading-specific guidelines to be followed by the brokerage firms and FinTech companies in charge of creating trading software.

- Rating organizations should include security in their reviews.

Side Note

Remember: the stock market is not a casino where you magically get rich overnight. If you lack an understanding of how stocks or other financial instruments work, there is a high risk of losing money quickly. You must understand the market and its purpose before investing.

With nothing left to say, I wish you happy and secure trading!

Thanks for reading,

Alejandro

@nitr0usmx

This blog post contains a small portion of the entire analysis.

Please refer to the white paper.