Greetings! I’m Corey Thuen. I spent a number of years at Idaho National Laboratory, Digital Bond, and IOActive (where we affectionately refer to ourselves as pirates, hence the sticker). At these places, my job was to find 0-day vulnerabilities on the offensive side of things.

Now, I am a founder of Gravwell, a data analytics platform for security logs, machine, and network data. It’s my background in offensive security that informs my new life on the defensive side of the house. I believe that defense involves more than looking for how threat actor XYZ operates, it requires an understanding of the environment and maximizing the primary advantage that defense has—this is your turf and no one knows it like you do. One of my favorite quotes about security comes from Dr. Eugene Spafford at Purdue (affectionately known in the cybersecurity community as “Spaf”) who said, “A system is good if it does what it’s supposed to do, and secure if it doesn’t do anything else.” We help our customers use data to make their systems good and secure, but for this post let’s talk bad guys, 0-days, and hiding in the noise.

A very important part of cybersecurity is threat actor analysis and IOC generation. Security practitioners benefit from knowledge about how adversary groups and their toolkits behave. Having an IOC for a given vulnerability is a strong signal, useful for threat detection and mitigation. But what about for one-off actors or 0-day vulnerabilities? How do we sort through the million trillion events coming out of our systems to find and mitigate attacks?

IOActive has a lot of great folks in the pirate crew, but at this point I want to highlight a pre-pandemic talk from Jason Larsen about actor inflation. His thesis and discussion are both interesting and hilarious; the talk is certainly worth a watch. But to tl;dr it for you, APT groups are not the only attackers interested in, or capable of, compromising your systems. Not by a long shot.

When I was at IOActive (also Digital Bond and Idaho National Laboratory), it was my job as a vulnerability researcher to find 0-days and provide detailed technical write-ups for clients so vulnerabilities could be discovered and remediated. It’s this work that gives me a little different perspective when it comes to event collection and correlation for security purposes. I have a great appreciation for weak signals. As an attacker, I want my signals to the defenders to be as weak as possible. Ideally, they blend into the noise of the target environment. As a defender, I want to filter out the noise and increase the fidelity of attacker signals.

Hiding in the Data: Weak Signals

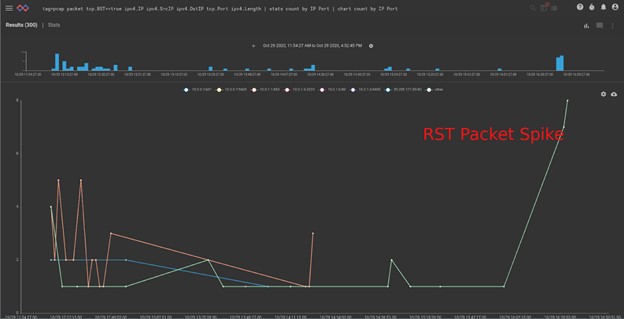

What is a weak signal? Let’s talk about an example vulnerability in some ICS equipment. Exploiting this particular vulnerability required sending a series of payloads to the equipment until exploitation was possible. Actually exploiting the vulnerability did not cause the device to crash (which often happens with ICS gear), nor did it cause any other obvious functionality issues. However, the equipment would terminate the network communication with an RST packet after each exploit attempt. Thus, one might say an IOC would be an “unusual number of RST packets.”

Now, any of you readers who have actually been in a SOC are probably painfully aware of the problems that occur when you treat weak signals as strong signals. Computers do weird shit sometimes. Throw in users and weird shit happens a lot of the time. If you were to set up alerts on RST packet indicators, you would quickly be inundated; that alert is getting switched off immediately. This is one area where AI/ML can actually be pretty helpful, but that’s a topic for another post.

The fact that a given cyber-physical asset has an increased number of RST packets is a weak signal. Monitoring RST packet frequency itself is not that helpful and, if managed poorly, can actually cause decreased visibility. This brings us to the meat of this post: multiple disparate weak signals can be fused into a strong signal.

Let’s add in a fictitious attacker who has a Metasploit module to exploit the vulnerability I just described. She also has the desire to participate in some DDoS, because she doesn’t actually realize that this piece of equipment is managing really expensive and critical industrial processes (such a stretch, I know, but let’s exercise our imaginations). Once exploited, the device attempts to communicate with an IP address to which it has never communicated previously—another weak signal. Network whitelisting can be effective in certain environments, but an alert every time a whitelist is violated is going to be way way too many alerts. You should still collect them for retrospective analysis (get yourself an analytics platform that doesn’t charge for every single event you put in), but every network whitelist change isn’t going to warrant action by a human.

As a final step in post-exploitation, the compromised device initiates multiple network sockets to a slack server, above the “normal” threshold for connection counts coming out of this device on a given day. Another weak signal.

So what has the attacker given a defender? We have an increased RST packet count, a post-exploitation download from a new IP address, and then a large uptick in outgoing connections. Unless these IP addresses trigger on some threat list, they could easily slide by as normal network activity hidden in the noise.

An analyst who has visibility into NetFlow and packet data can piece these weak signals together into a strong signal that actually warrants getting a human involved; this is now a threat hunt. This type of detection can be automated directly in an analytics platform or conducted using an advanced IDS that doesn’t rely exclusively on IOCs. When it comes to cybersecurity, the onus is on the defender to fuse these weak signals in their environment. Out-of-the-box security solutions are going to fail in this department because, by nature, they are built for very specific situations. No two organizations have exactly the same network architecture or exactly the same vendor choices for VPNs, endpoints, collaboration software, etc. The ability to fuse disparate data together to create meaningful decisions for a given organization is crucial to successful defense and successful operations.

Hiding Weak Signals in Time

One other very important aspect of weak signals is time. As humans, we are particularly susceptible to this problem but the detection products on the market face challenges here too. A large amount of activity or a large change in a short amount of time becomes very apparent. The frame of reference is important for human pattern recognition and anomaly detection algorithms. Just about any sensor will throw a “port scan happened” alert if you `nmap -T5 -p- 10.0.0.1-255.` What about if you only send one packet per second? What about one per day? Detection sensors encounter significant technical challenges keeping context over long periods of time when you consider that some organizations are generating many terabytes of data every day.

An attacker willing to space activity out over time is much less likely to be detected unless defenders have the log retention and analytics capability to make time work for defense. Platforms like Gravwell and Splunk were built for huge amounts of time series data, and there are open-source time series databases, like InfluxDB, that can provide these kinds of time-aware analytics. Key/value stores like ELK can also work, but they weren’t explicitly built for time series, and time-series-first is probably necessary at scale. It’s also possible to do these kinds of time-based data science activities using Python scripts, but I wouldn’t recommend it.

Conclusion

Coming from a background in vulnerability research, I understand how little it can take to compromise a host and how easily that compromise can be lost in the noise when there are no existing, high-fidelity IOCs. This doesn’t just apply to exploits, but also lost credentials and user behavior.

Relying exclusively on pre-defined IOCs, APT detection mechanisms or other “out-of-the-box” solutions causes a major gap in visibility and gives up the primary advantage that you have as a defender: this is your turf. Over time, weak signals are refined and automated analysis can be put in place to make any attacker stepping foot into your domain stand out like a sore thumb.

Data collection is the first step to detecting and responding to weak signals. I encourage organizations to collect as much data as possible. Storage is cheap and you can’t know ahead of time which logfile or piece of data is going to end up being crucial to an investigation.

With the capability to fuse weak signals into a high-fidelity, strong signal on top of pure strong signal indicators and threat detection, an organization is poised to be successful and make sure their systems “do what they’re supposed to do, and don’t do anything else.”

-Corey Thuen