Tag: ioactive labs

The password is irrelevant

A Short Tale About executable_stack in elf_read_implies_exec() in the Linux Kernel

#include <unistd.h>

char shellcode[] =

“x48x31xd2x48x31xf6x48xbf”

“x2fx62x69x6ex2fx73x68x11”

“x48xc1xe7x08x48xc1xefx08”

“x57x48x89xe7x48xb8x3bx11”

“x11x11x11x11x11x11x48xc1”

“xe0x38x48xc1xe8x38x0fx05”;

int main(int argc, char ** argv) {

void (*fp)();

fp = (void(*)())shellcode;

(void)(*fp)();

return 0;

}

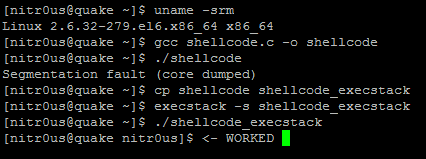

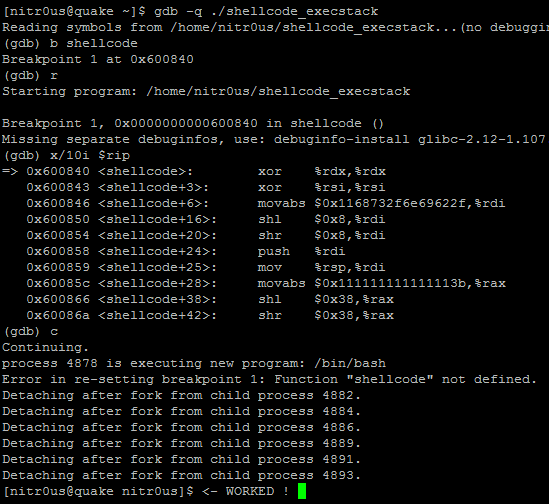

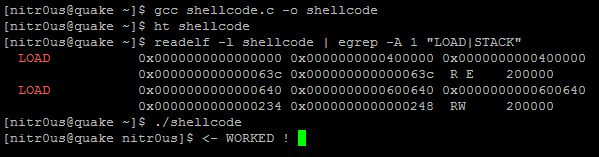

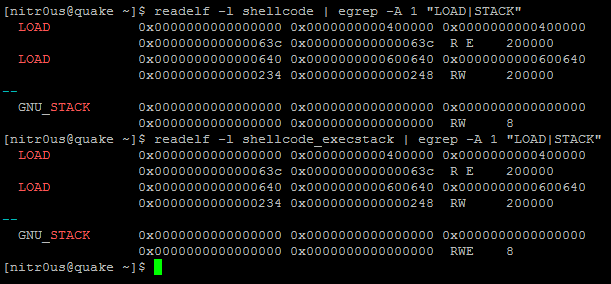

Immediately, I thought it was wrong because of the code to be executed would be placed in the ‘shellcode’ symbol in the .data section within the ELF file, which, in turn, would be in the data memory segment, not in the stack segment at runtime. For some reason, when trying to execute it without enabling the executable stack bit, it failed, and the opposite when it was enabled:

According to the execstack’s man-page:

The first loadable segment in both binaries, with the ‘E’ flag enabled, is where the code itself resides (the .text section) and the second one is where all our data resides. It’s also possible to map which bytes from each section correspond to which memory segments (remember, at runtime, the sections are not taken into account, only the program headers) using ‘readelf -l shellcode’.

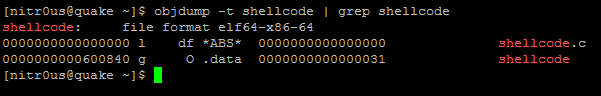

So far, everything makes sense to me, but, wait a minute, the shellcode, or any other variable declared outside main(), is not supposed to be in the stack right? Instead, it should be placed in the section where the initialized data resides (as far as I know it’s normally in .data or .rodata). Let’s see where exactly it is by showing the symbol table and the corresponding section of each symbol (if it applies):

It’s pretty clear that our shellcode will be located at the memory address 0x00600840 in runtime and that the bytes reside in the .data section. The same result for the other binary, ‘shellcode_execstack’.

By default, the data memory segment doesn’t have the PF_EXEC flag enabled in its program header, that’s why it’s not possible to jump and execute code in that segment at runtime (Segmentation Fault), but: when the stack is executable, why is it also possible to execute code in the data segment if it doesn’t have that flag enabled?

Is it a normal behavior or it’s a bug in the dynamic linker or kernel that doesn’t take into account that flag when loading ELFs? So, to take the dynamic linker out of the game, my fellow Ilja van Sprundel gave me the idea to compile with -static to create a standalone executable. A static binary doesn’t pass through the dynamic linker, instead, it’s loaded directly by the kernel (as far as I know). The same result was obtained with this one, so this result pointed directly to the kernel.

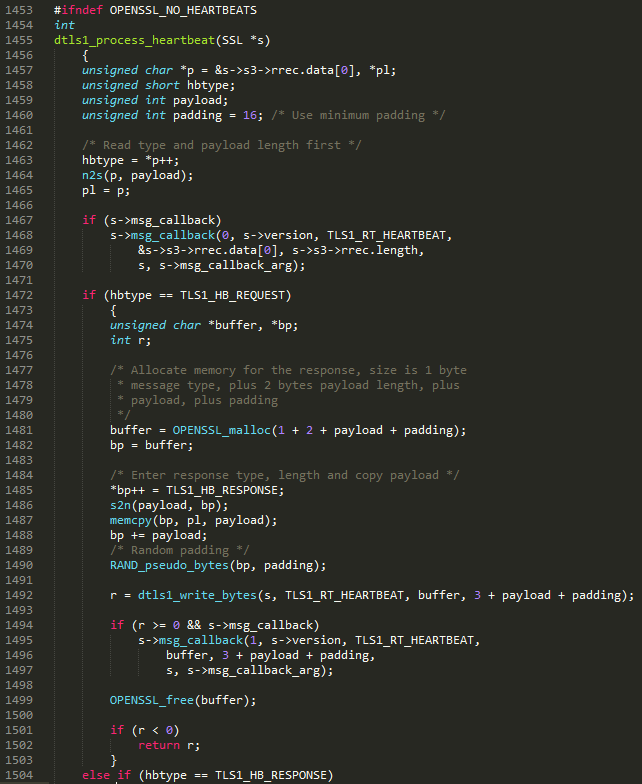

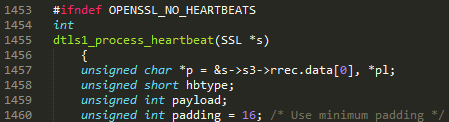

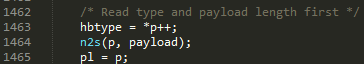

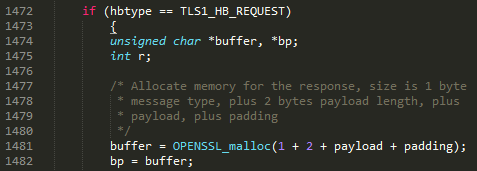

Now, for the interesting part, what is really happening in the kernel side? I went straight to load_elf_binary()in linux-2.6.32.61/fs/binfmt_elf.c and found that the program header table is parsed to find the stack segment so as to set the executable_stack variable correctly:

int executable_stack = EXSTACK_DEFAULT;

…

elf_ppnt = elf_phdata;

for (i = 0; i < loc->elf_ex.e_phnum; i++, elf_ppnt++)

if (elf_ppnt->p_type == PT_GNU_STACK) {

if (elf_ppnt->p_flags & PF_X)

executable_stack = EXSTACK_ENABLE_X;

else

executable_stack = EXSTACK_DISABLE_X;

break;

}

Keep in mind that only those three constants about executable stack are defined in the kernel (linux-2.6.32.61/include/linux/binfmts.h):

/* Stack area protections */

#define EXSTACK_DEFAULT 0 /* Whatever the arch defaults to */

#define EXSTACK_DISABLE_X 1 /* Disable executable stacks */

#define EXSTACK_ENABLE_X 2 /* Enable executable stacks */

Later on, the process’ personality is updated as follows:

/* Do this immediately, since STACK_TOP as used in setup_arg_pages may depend on the personality. */

SET_PERSONALITY(loc->elf_ex);

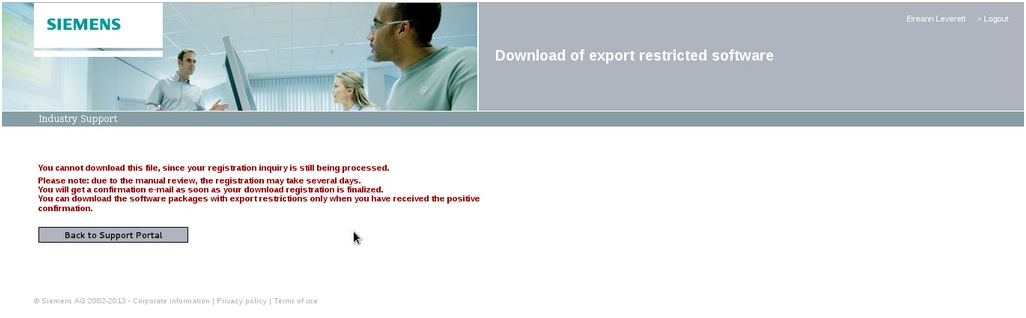

if (elf_read_implies_exec(loc->elf_ex, executable_stack))

current->personality |= READ_IMPLIES_EXEC;

if (!(current->personality & ADDR_NO_RANDOMIZE) && randomize_va_space)

current->flags |= PF_RANDOMIZE;

…

elf_read_implies_exec() is a macro in linux-2.6.32.61/arch/x86/include/asm/elf.h:

/*

* An executable for which elf_read_implies_exec() returns TRUE

* will have the READ_IMPLIES_EXEC personality flag set automatically.

*/

#define elf_read_implies_exec(ex, executable_stack)

(executable_stack != EXSTACK_DISABLE_X)

In our case, having an ELF binary with the PF_EXEC flag enabled in the PT_GNU_STACK program header, that macro will return TRUE since EXSTACK_ENABLE_X != EXSTACK_DISABLE_X, thus, our process’ personality will have READ_IMPLIES_EXEC flag. This constant, READ_IMPLIES_EXEC, is checked in some memory related functions such as in mmap.c, mprotect.c and nommu.c (all in linux-2.6.32.61/mm/). For instance, when creating the VMAs (Virtual Memory Areas) by the do_mmap_pgoff() function in mmap.c, it verifies the personality so it can add the PROT_EXEC (execution allowed) to the memory segments [1]:

/*

* Does the application expect PROT_READ to imply PROT_EXEC?

*

* (the exception is when the underlying filesystem is noexec

* mounted, in which case we dont add PROT_EXEC.)

*/

if ((prot & PROT_READ) && (current->personality & READ_IMPLIES_EXEC))

if (!(file && (file->f_path.mnt->mnt_flags & MNT_NOEXEC)))

prot |= PROT_EXEC;

And basically, that’s the reason of why code in the data segment can be executed when the stack is executable.

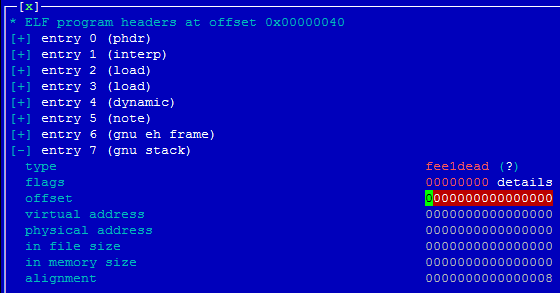

On the other hand, I had an idea: to delete the PT_GNU_STACK program header by changing its corresponding program header type to any other random value. Doing that, executable_stack would remain EXSTACK_DEFAULT when compared in elf_read_implies_exec(), which would return TRUE, right? Let’s see:

The program header type was modified from 0x6474e551 (PT_GNU_STACK) to 0xfee1dead, and note that the second LOAD (data segment, where our code to be executed is) doesn’t have the ‘E’xecutable flag enabled:

#define elf_read_implies_exec(ex, executable_stack)

(executable_stack == EXSTACK_ENABLE_X)

Anyway, perhaps that’s the normal behavior of the Linux kernel for some compatibility issues or something else, but isn’t it weird that making the stack executable or deleting the PT_GNU_STACK header all the memory segments are loaded with execution permissions even when the PF_EXEC flag is not set?

#define elf_read_implies_exec(ex, executable_stack) (executable_stack != EXSTACK_DISABLE_X)

#define INTERPRETER_NONE 0

#define INTERPRETER_ELF 2

Car Hacking: The Content

DefCon 21 Preview

“Adventures in Automotive Networks and Control Units” (Track 3)

(https://www.defcon.org/html/defcon-21/dc-21-schedule.html)

- We will briefly discuss the ISO / Protocol standards that our two automobiles used to communicate on the CAN bus, also providing a Python and C API that can be used to replicate our work. The API is pretty generic so it can easily be modified to work with other makes / models.

- The first type of CAN traffic we’ll discuss is diagnostic CAN messages. These types of message are usually used by mechanics to diagnose problems within the automotive network, sensors, and actuators. Although meant for maintenance, we’ll show how some of these messages can be used to physically control the automobile under certain conditions.

- The second type of CAN data we’ll talk about is normal CAN traffic that the car regularly produces. These types of CAN messages are much more abundant but more difficult to reverse engineer and categorize (i.e. proprietary messages). Although time consuming, we’ll show how these messages, when played on the CAN network, have control over the most safety critical features of the automobile.

- Finally we’ll talk about modifying the firmware and using the proprietary re-flashing processes used for each of our vehicles. Firmware modification is most likely necessary for any sort of persistence when attempting to permanently modify an automobile’s behavior. It will also show just how different this process is for each make/model, proving that ‘just ask the tuning community’ is not a viable option a majority of the time.

IOAsis at RSA 2013

RSA has grown significantly in the 10 years I’ve been attending, and this year’s edition looks to be another great event. With many great talks and networking events, tradeshows can be a whirlwind of quick hellos, forgotten names, and aching feet. For years I would return home from RSA feeling as if I hadn’t sat down in a week and lamenting all the conversations I started but never had the chance to finish. So a few years ago during my annual pre-RSA Vitamin D-boosting trip to a warm beach an idea came to me: Just as the beach served as my oasis before RSA, wouldn’t it be great to give our VIPs an oasis to escape to during RSA? And thus the first IOAsis was born.

Aside from feeding people and offering much needed massages, the IOAsis is designed to give you a trusted environment to relax and have meaningful conversations with all the wonderful folks that RSA, and the surrounding events such as BSidesSF, CSA, and AGC, attract. To help get the conversations going each year we host a number of sessions where you can join IOActive’s experts, customers, and friends to discuss some of the industry’s hottest topics. We want these to be as interactive as possible, so the following is a brief look inside some of the sessions the IOActive team will be leading.

(You can check out the full IOAsis schedule of events at:

Chris Valasek @nudehaberdasher

Second, Stephan Chenette and I will talking about assessing modern attacks against PCs at IOAsis on Wednesday at 1:00-1:45. We believe that security is too often described in binary terms — “Either you ARE secure or you are NOT secure — when computer security is not an either/or proposition. We will examine current mainstream attack techniques, how we plan non-binary security assessments, and finally why we think changes in methodologies are needed. I’d love people to attend either presentation and chat with me afterwards. See everyone at RSA 2013!

By Gunter Ollman @gollmann

My RSA talk (Wednesday at 11:20), “Building a Better APT Package,” will cover some of the darker secrets involved in the types of weaponized malware that we see in more advanced persistent threats. In particular I’ll discuss the way payloads are configured and tested to bypass the layers of defensive strata used by security-savvy victims. While most “advanced” features of APT packages are not very different from those produced by commodity malware vendors, there are nuances to the remote control features and levels of abstraction in more advanced malware that are designed to make complete attribution more difficult.

Over in the IOAsis refuge on Wednesday at 4:00 I will be leading a session with my good friend Bob Burls on “Fatal Mistakes in Incident Response.” Bob recently retired from the London Metropolitan Police Cybercrime Division, where he led investigations of many important cybercrimes and helped put the perpetrators behind bars. In this session Bob will discuss several complexities of modern cybercrime investigations and provide tips, gotcha’s, and lessons learned from his work alongside corporate incident response teams. By better understanding how law enforcement works, corporate security teams can be more successful in engaging with them and receive the attention and support they believe they need.

By Stephan Chenette @StephanChenette

At IOAsis this year Chris Valasek and I will be presenting on a topic that builds on my Offensive Defense talk and starts a discussion about what we can do about it.

For too long both Chris and I have witnessed the “old school security mentality” that revolves solely around chasing vulnerabilities and remediation of vulnerable machines to determine risk. In many cases the key motivation is regulatory compliance. But this sort of mind-set doesn’t work when you are trying to stop a persistent attacker.

What happens after the user clicks a link or a zero-day attack exploits a vulnerability to gain entry into your network? Is that part of the risk assessment you have planned for? Have you only considered defending the gates of your network? You need to think about the entire attack vector: Reconnaissance, weaponization, delivery, exploitation, installation of malware, and command and control of the infected asset are all strategies that need further consideration by security professionals. Have you given sufficient thought to the motives and objectives of the attackers and the techniques they are using? Remember, even if an attacker is able to get into your network as long as they aren’t able to destroy or remove critical data, the overall damage is limited.

Chris and I are working on an R&D project that we hope will shake up how the industry thinks about offensive security by enabling us to automatically create non-invasive scenarios to test your holistic security architecture and the controls within them. Do you want those controls to be tested for the first time in a real-attack scenario, or would you rather be able to perform simulations of various realistic attacker scenarios, replayed in an automated way producing actionable and prioritized items?

Our research and deep understanding of hacker techniques enables us to catalog various attack scenarios and replay them against your network, testing your security infrastructure and controls to determine how susceptible you are today’s attacks. Join us on Wednesday at 1:00 to discuss this project and help shape its future.

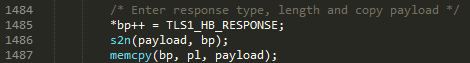

2012 Vulnerability Disclosure Retrospective

Vulnerabilities, the bugbear of system administrators and security analysts alike, keep on piling up – ruining Friday nights and weekends around the world as those tasked with fixing them work against ever shortening patch deadlines.

In recent years the burden of patching vulnerable software may have felt to be lessening; and it was, if you were to go by the annual number of vulnerabilities publicly disclosed. However, if you thought 2012 was a little more intense than the previous half-decade, you’ll probably not be surprised to learn that last year bucked the downward trend and saw a rather big jump – 26% over 2011 – all according to the latest analyst brief from NSS Labs, “Vulnerability Threat Trends: A Decade in Review, Transition on the Way”.

Rather than summarize the fascinating brief from NSS Labs with a list of recycled bullet points, I’d encourage you to read it yourself and to view the fascinating video they constructed that depicts the rate and diversity of vulnerability disclosures throughout 2012 (see the video – “The Evolution of 2012 Vulnerability Disclosures by Vendor”).

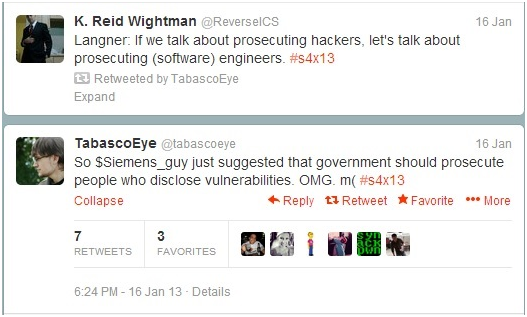

I was particularly interested in the Industrial Control System (ICS/SCADA) vulnerability growth – a six-fold increase since 2010! Granted, of the 5225 vulnerabilities publicly disclosed and tracked in 2012 only 124 were ICS/SCADA related (2.4 percent), it’s still noteworthy – especially since I doubt very few of vulnerabilities in this field are ever disclosed publicly.

Once you’ve read the NSS Labs brief and digested the statistics, let me tell you why the numbers don’t really matter and why the ranking of vulnerable vendors is a bit like ranking car manufacturers by the number of red cars they sold last year.

A decade ago, as security software and appliance vendors battled for customer dollars, vulnerability numbers mattered. It was a yardstick of how well one security product (and vendor) was performing against another – a kind of “my IDS detects 87% of high risk vulnerabilities” discussion. When the number of vulnerability disclosures kept on increasing and the cost of researching and developing detection signatures kept going up, yet the price customers were willing to pay in maintenance fees for their precious protection technologies was going down, much of the discussion then moved to ranking and scoring vulnerabilities… and the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) was devised.

CVSS changed the nature of the game. It became less about covering a specific percentage of vulnerabilities and more about covering the most critical and exploitable. The ‘High, Medium, and Low’ of old, got augmented with a formal scoring system and a bevy of new labels such as ‘Critical’ and ‘Highly Critical’ (which, incidentally, makes my teeth hurt as I grind them at the absurdity of that term). Rather than simply shuffling everything to the right, with the decade old ‘Medium’ becoming the new ‘Low’, and the old ‘Low’ becoming a shrug and a sensible “if you can be bothered!”… we ended up with ‘High’ being “important, fix immediately”, then ‘Critical’ assuming the role of “seriously, you need to fix this one first!”, and ‘Highly Critical’ basically meaning “Doh! The Mayans were right, the world really is going to end!”

But I digress. The crux of the matter as to why annual vulnerability statistics don’t matter and will continue to matter less in a practical sense as times goes by is because they only reflect ‘Disclosures’. In essence, for a vulnerability to be counted (and attribution applied) it must be publicly disclosed, and more people are finding it advantageous to not do that.

Vulnerability markets and bug purchase programs – white, gray and black – have changed the incentive to disclose publicly, as well as limit the level of information that is made available at the time of disclosure. Furthermore, the growing professionalization of bug hunting has meant that vulnerability discoveries are valuable commercial commodities – opening doors to new consulting engagements and potential employment with the vulnerable vendor. Plus there’s a bunch of other lesser reasons why public disclosures (as a percentage of actual vulnerabilities found by bug hunters and reported to vendors) will go down.

The biggest reason why the vulnerability disclosures numbers matter less and less to an organization (and those charged with protecting it), is because the software landscape has fundamentally changed. The CVSS approach was primarily designed for software that was brought, installed and operated by multiple organizations – i.e. software packages that could be patched by their many owners.

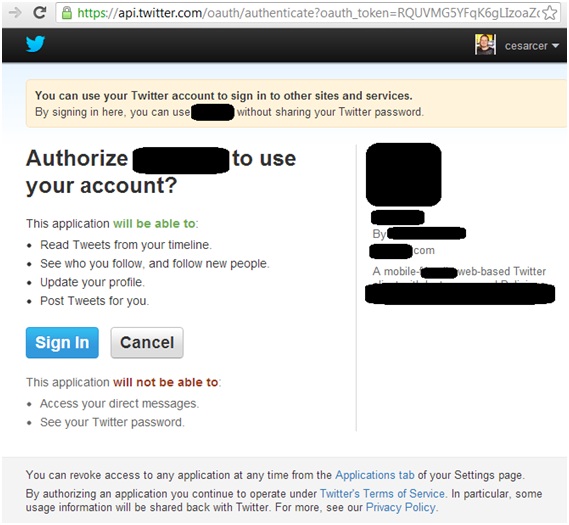

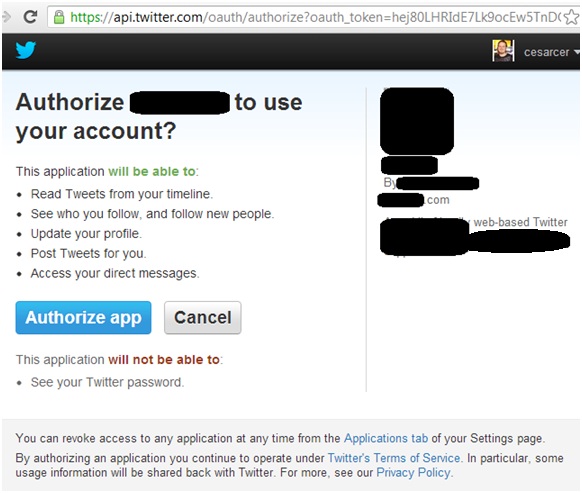

With today’s ubiquitous cloud-based services – you don’t own the software and you don’t have any capability (or right) to patch the software. Whether it’s Twitter, Salesforce.com, Dropbox, Google Docs, or LinkedIn, etc. your data and intellectual property is in the custodial care of a third-party who doesn’t need to publicly disclose the nature (full or otherwise) of vulnerabilities lying within their backend systems – in fact most would argue that it’s in their best interest to not make any kind of disclosure (ever!).

Why would someone assign a CVE number to the vulnerability? Who’s going to have all the disclosure details to construct a CVSS score, and what would it matter if they did? Why would the service provider issue an advisory? As a bug hunter who responsibly discloses the vulnerability to the cloud service provider you’d be lucky to even get any public recognition for your valuable help.

With all that said and done, what should we take-away from the marvelous briefing that NSS Labs has pulled together? In essence, there’s a lot of vulnerabilities being disclosed and the vendors of the software we deploy on our laptops and servers still have a ways to go to improving their security development lifecycle (SDL) – some more than others.

While it would be nice to take some solace in the ranking of vulnerable vendors, I’d be more worried about the cloud vendors and their online services and the fact that they’re not showing up in these annual statistics – after all, that’s were more and more of our critical data is being stored and manipulated.

— Gunter Ollmann, CTO — IOActive, Inc.

Offensive Defense

I presented before the holiday break at Seattle B-Sides on a topic I called “Offensive Defense.” This blog will summarize the talk. I feel it’s relevant to share due to the recent discussions on desktop antivirus software (AV)

What is Offensive Defense?

The basic premise of the talk is that a good defense is a “smart” layered defense. My “Offensive Defense” presentation title might be interpreted as fighting back against your adversaries much like the Sexy Defense talk my co-worker Ian Amit has been presenting.

My view of the “Offensive Defense” is about being educated on existing technology and creating a well thought-out plan and security framework for your network. The “Offensive” word in the presentation title relates to being as educated as any attacker who is going to study common security technology and know it’s weaknesses and boundaries. You should be as educated as that attacker to properly build a defensive and reactionary security posture. The second part of an “Offensive Defense” is security architecture. It is my opinion that too many organizations buy a product to either meet the minimal regulatory requirements, to apply “band-aide” protection (thinking in a point manner instead of a systematic manner), or because the organization thinks it makes sense even though they have not actually made a plan for it. However, many larger enterprise companies have not stepped back and designed a threat model for their network or defined the critical assets they want to protect.

At the end of the day, a persistent attacker will stop at nothing to obtain access to your network and to steal critical information from your network. Your overall goal in protecting your network should be to protect your critical assets. If you are targeted, you want to be able to slow down your attacker and the attack tools they are using, forcing them to customize their attack. In doing so, your goal would be to give away their position, resources, capabilities, and details. Ultimately, you want to be alerted before any real damage has occurred and have the ability to halt their ability to ex-filtrate any critical data.

Conduct a Threat Assessment, Create a Threat Model, Have a Plan!

This process involves either having a security architect in-house or hiring a security consulting firm to help you design a threat model tailored to your network and assess the solutions you have put in place. Security solutions are not one-size fits all. Do not rely on marketing material or sales, as these typically oversell the capabilities of their own product. I think in many ways overselling a product is how as an industry we have begun to have rely too heavily on security technologies, assuming they address all threats.

There are many quarterly reports and resources that technical practitioners turn to for advice such as Gartner reports, the magic quadrant, or testing houses including AV-Comparatives, ICSA Labs, NSS Labs, EICAR or AV-Test. AV-Test , in fact, reported this year that Microsoft Security Essentials failed to recognize enough zero-day threats with detection rates of only 69% , where the average is 89%. These are great resources to turn to once you know what technology you need, but you won’t know that unless you have first designed a plan.

Once you have implemented a plan, the next step is to actually run exercises and, if possible, simulations to assess the real-time ability of your network and the technology you have chosen to integrate. I rarely see this done, and, in my opinion, large enterprises with critical assets have no excuse not to conduct these assessments.

Perform a Self-assessment of the Technology

AV-Comparatives has published a good quote on their product page that states my point:

“If you plan to buy an Anti-Virus, please visit the vendor’s site and evaluate their software by downloading a trial version, as there are also many other features and important things for an Anti-Virus that you should evaluate by yourself. Even if quite important, the data provided in the test reports on this site are just some aspects that you should consider when buying Anti-Virus software.”

This statement proves my point in stating that companies should familiarize themselves with a security technology to make sure it is right for their own network and security posture.

There are many security technologies that exist today that are designed to detect threats against or within your network. These include (but are not limited to):

- Firewalls

- Intrusion Prevention Systems (IPS)

- Intrusion Detectoin Systems (IDS)

- Host-based Intrusion Prevention Systems (HIPS)

- Desktop Antivirus

- Gateway Filtering

- Web Application Firewalls

- Cloud-Based Antivirus and Cloud-based Security Solutions

Such security technologies exist to protect against threats that include (but are not limited to):

- File-based malware (such as malicious windows executables, Java files, image files, mobile applications, and so on)

- Network-based exploits

- Content based exploits (such as web pages)

- Malicious email messages (such as email messages containing malicious links or phishing attacks)

- Network addresses and domains with a bad reputation

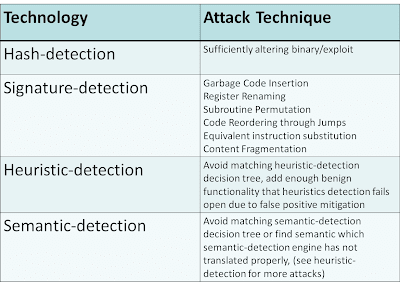

These security technologies deploy various techniques that include (but are not limited to):

- Hash-detection

- Signature-detection

- Heuristic-detection

- Semantic-detection

- Reputation-based

- Behavioral based

For the techniques that I have not listed in this table such as reputation, refer to my CanSecWest 2008 presentation “Wreck-utation“, which explains how reputation detection can be circumvented. One major example of this is a rising trend in hosting malicious code on a compromised legitimate website or running a C&C on a legitimate compromised business server. Behavioral sandboxes can also be defeated with methods such as time-lock puzzles and anti-VM detection or environment-aware code. In many cases, behavioral-based solutions allow the binary or exploit to pass through and in parallel run the sample in a sandbox. This allows what is referred to as a 1-victim-approach in which the user receiving the sample is infected because the malware was allowed to pass through. However, if it is determined in the sandbox to be malicious, all other users are protected. My point here is that all methods can be defeated given enough expertise, time, and resources.

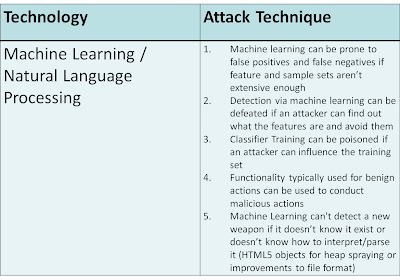

Big Data, Machine Learning, and Natural Language Processing

My presentation also mentioned something we hear a lot about today… BIG DATA. Big Data plus Machine Learning coupled with Natural Language Processing allows a clustering or classification algorithm to make predictive decisions based on statistical and mathematical models. This technology is not a replacement for what exists. Instead, it incorporates what already exists (such as hashes, signatures, heuristics, semantic detection) and adds more correlation in a scientific and statistic manner. The growing number of threats combined with a limited number of malware analysts makes this next step virtually inevitable.

While machine learning, natural language processing, and other artificial intelligence sciences will hopefully help in supplementing the detection capabilities, keep in mind this technology is nothing new. However, the context in which it is being used is new. It has already been used in multiple existing technologies such as anti-spam engines and Google translation technology. It is only recently that it has been applied to Data Leakage Prevention (DLP), web filtering, and malware/exploit content analysis. Have no doubt, however, that like most technologies, it can still be broken.

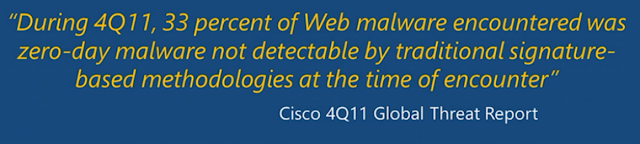

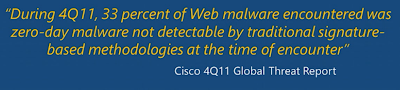

Hopefully most of you have read Imperva’s report, which found that less than 5% of antivirus solutions are able to initially detect previously non-cataloged viruses. Regardless of your opinion on Imperva’s testing methodologies, you might have also read the less-scrutinized Cisco 2011 Global Threat report that claimed 33% of web malware encountered was zero-day malware not detectable by traditional signature-based methodologies at the time of encounter. This, in my experience, has been a more widely accepted industry statistic.

What these numbers are telling us is that the technology, if looked at individually, is failing us, but what I am saying is that it is all about context. Penetrating defenses and gaining access to a non-critical machine is never desirable. However, a “smart” defense, if architected correctly, would incorporate a number of technologies, situated on your network, to protect the critical assets you care about most.

The Cloud versus the End-Point

If you were to attend any major conference in the last few years, most vendors would claim “the cloud” is where protection technology is headed. Even though there is evidence to show that this might be somewhat true, the majority of protection techniques (such as hash-detection, signature-detection, reputation, and similar technologies) simply were moved from the desktop to the gateway or “cloud”. The technology and techniques, however, are the same. Of course, there are benefits to the gateway or cloud, such as consolidated updates and possibly a more responsive feedback and correlation loop from other cloud nodes or the company lab headquarters. I am of the opinion that there is nothing wrong with having anti-virus software on the desktop. In fact, in my graduate studies at UCSD in Computer Science, I remember a number of discussions on the end-to-end arguments of system design, which argued that it is best to place functionality at end points and at the highest level unless doing otherwise improves performance.

The desktop/server is the end point where the most amount of information can be disseminated. The desktop/server is where context can be added to malware, allowing you to ask questions such as:

- Was it downloaded by the user and from which site?

- Is that site historically common for that particular user to visit?

- What happened after it was downloaded?

- Did the user choose to execute the downloaded binary?

- What actions did the downloaded binary take?

Hashes, signatures, heuristics, semantic-detection, and reputation can all be applied at this level. However, at a gateway or in the cloud, generally only static analysis is performed due to latency and performance requirements.

This is not to say that gateway or cloud security solutions cannot observe malicious patterns at the gateway, but restraints on state and the fact that this is a network bottleneck generally makes any analysis node after the end point thorough. I would argue that both desktop and cloud or gateway security solutions have their benefits though, and if used in conjunction, they add even more visibility into the network. As a result, they supplement what a desktop antivirus program cannot accomplish and add collective analysis.

Conclusion

My main point is that to have a secure network you have to think offensively by architecting security to fit your organization needs. Antivirus software on the desktop is not the problem. The problem is the lack of planing that goes into deployment as well as the lack of understanding in the capabilities of desktop, gateway, network, and cloud security solutions. What must change is the haste with which network teams deploy security technologies without having a plan, a threat model, or a holistic organizational security framework in place that takes into account how all security products work together to protect critical assets.

With regard to the cloud, make no mistake that most of the same security technology has simply moved from the desktop to the cloud. Because it is at the network level, the latency of being able to analyze the file/network stream is weaker and fewer checks are performed for the sake of user performance. People want to feel safe relying on the cloud’s security and feel assured knowing that a third-party is handling all security threats, and this might be the case. However, companies need to make sure a plan is in place and that they fully understand the capabilities of the security products they have chosen, whether they be desktop, network, gateway, or cloud based.

If you found this topic interesting, Chris Valasek and I are working on a related project that Chris will be presenting at An Evening with IOActive on Thursday, January 17, 2013. We also plan to talk about this at the IOAsis at the RSA Conference. Look for details!

The Future of Automated Malware Generation

This year I gave a series of presentations on “The Future of Automated Malware Generation”. This past week the presentation finished its final debut in Tokyo on the 10th anniversary of PacSec.

Hopefully you were able to attend one of the following conferences where it was presented:

- IOAsis (Las Vegas, USA)

- SOURCE (Seattle, USA)

- EkoParty (Buenos Aires, Argentina)

- PacSec (Tokyo, Japan)

Motivation / Intro

- Greg Hoglund’s talk at Blackhat 2010 on malware attribution and fingerprinting

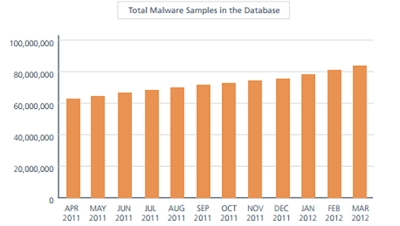

- The undeniable steady year by year increase in malware, exploits and exploit kits

- My unfinished attempt in adding automatic classification to the cuckoo sandbox

- An attempt to clear up the perception by many consumers and corporations that many security products are resistant to simple evasion techniques and contain some “secret sauce” that sets them apart from their competition

- The desire to educate consumers and corporations on past, present and future defense and offense techniques

- Lastly to help reemphasize the philosophy that when building or deploying defensive technology it’s wise to think offensively…and basically try to break what you build

Current State of Automated Malware Generation

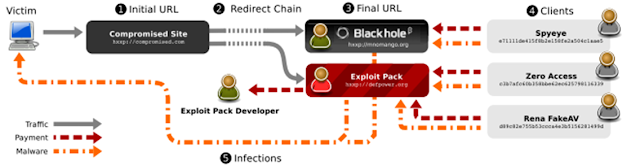

Automated Malware Generation centers on Malware Distribution Networks (MDNs).

MDNs are organized, distributed networks that are responsible for the entire exploit and infection vector.

There are several players involved:

- Pay-per-install client – organizations that write malware and gain a profit from having it installed on as many machines as possible

- Pay-per-install services – organizations that get paid to exploit and infect user machines and in many cases use pay-per-install affiliates to accomplish this

- Pay-per-install affiliates – organizations that own a lot of infrastructure and processes necessary to compromise web legitimate pages, redirect users through traffic direction services (TDSs), infect users with exploits (in some cases exploit kits) and finally, if successful, download malware from a malware repository.

Source: Manufacturing Compromise: The Emergence of Exploit-as-a-Service

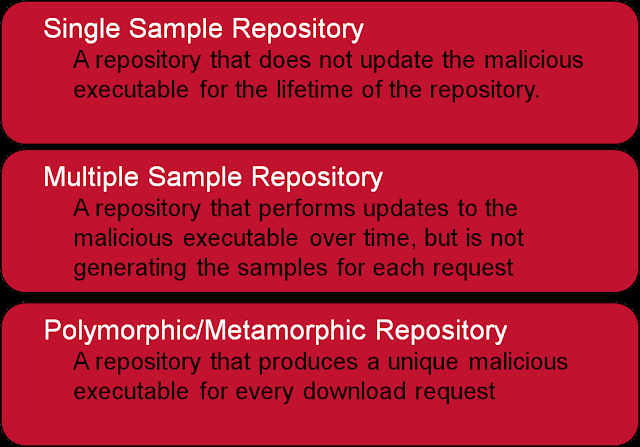

Figure: Basic Break-down of Malware Repository Types

Current State of Malware Defense

- hashes – cryptographic checksums of either the entire malware file or sections of the file, in some cases these could include black-listing and white-listing

- signatures – syntactical pattern matching using conditional expressions (in some cases format-aware/contextual)

- heuristics – An expression of characteristics and actions using emulation, API hooking, sand-boxing, file anomalies and/or other analysis techniques

- semantics – transformation of specific syntax into a single abstract / intermediate representation to match from using more abstract signatures and heuristics

EVERY defense technique can be broken – with enough time, skill and resources.

In the above defensive techniques:

- hash-based detection can be broken by changing the binary by a single byte

- signature-based detection be broken using syntax mutation

e.g.- Garbage Code Insertion e.g. NOP, “MOV ax, ax”, “SUB ax 0”

- Register Renaming e.g. using EAX instead of EBX (as long as EBX isn’t already being used)

- Subroutine Permutation – e.g. changing the order in which subroutines or functions are called as long as this doesn’t effect the overall behavior

- Code Reordering through Jumps e.g. inserting test instructions and conditional and unconditional branching instructions in order to change the control flow

- Equivalent instruction substitution e.g. MOV EAX, EBX <-> PUSH EBX, POP EAX

- heuristics-based detection can be broken by avoiding the characteristics the heuristics engine is using or using uncommon instructions that the heuristics engine might be unable to understand in it’s emulator (if an emulator is being used)

- semantics-based detection can be broken by using techniques such as time-lock puzzle (semantics-based detection are unlikely to be used at a higher level such as network defenses due to performance issues) also because implementation requires extensive scope there is a high likelihood that not all cases have been covered. Semantic-based detection is extremely difficult to get right given the performance requirements of a security product.

There are a number of other examples where defense techniques were easily defeated by proper targeted research (generally speaking). Here is a recent post by Trail of Bits only a few weeks ago [Trail of Bits Blog] in their analysis of ExploitSheild’s exploitation prevention technology. In my opinion the response from Zero Vulnerability Labs was appropriate (no longer available), but it does show that a defense technique can be broken by an attacker if that technology is studied and understood (which isn’t that complicated to figure out).

Malware Trends

Check any number of reports and you can see the rise in malware is going up (keep in mind these are vendor reports and have a stake in the results, but being that there really is no other source for the information we’ll use them as the accepted experts on the subject) [Symantec] [Trend] McAfee [IBM X-Force] [Microsoft] [RSA]

So how can the security industry use automatic classification? Well, in the last few years a data-driven approach has been the obvious step in the process.

The Future of Malware Defense

With the increase in more malware, exploits, exploit kits, campaign-based attacks, targeted attacks, the reliance on automation will heave to be the future. The overall goal of malware defense has been to a larger degree classification and to a smaller degree clustering and attribution.

Thus statistics and data-driven decisions have been an obvious direction that many of the security companies have started to introduce, either by heavily relying on this process or as a supplemental layer to existing defensive technologies to help in predictive pattern-based analysis and classification.

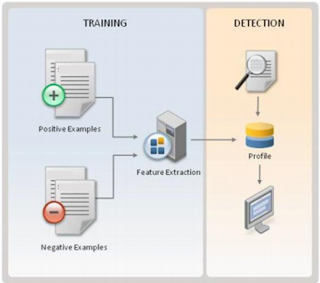

Training machine learning classifiers involves breaking down whatever content you want to analyze e.g. a network stream or an executable file into “features” (basically characteristics).

For example historically certain malware has:

- No icon

- No description or company in resource section

- Is packed

- Lives in windows directory or user profile

Each of the above qualities/characteristics can be considered “features”. Once the defensive technology creates a list of features, it then builds a parser capable of breaking down the content to find those features. e.g. if the content is a PE WIN32 executable, a PE parser will be necessary. The features would include anything you can think of that is characteristic of a PE file.

The process then involves training a classifier on a positive (malicious) and negative (benign) sample set. Once the classifier is trained it can be used to determine if a future unknown sample is benign or malicious and classify it accordingly.

- Compressed JavaScript

- PDF header location e.g %PDF – within first 1024 bytes

- Does it contain an embedded file (e.g. flash, sound file)

- Signed by a trusted certificate

- Encoded/Encrypted Streams e.g. FlatDecode is used quite a lot in malicious PDFs

- Names hex escaped

- Bogus xref table

There are two open-source projects that I want to mention using machine learning to determine if a file is malicious:

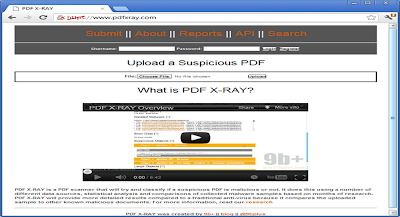

PDF-XRay from Brandon Dixon:

Adobe Open Source Malware Classification Tool by Karthik Raman/Adobe

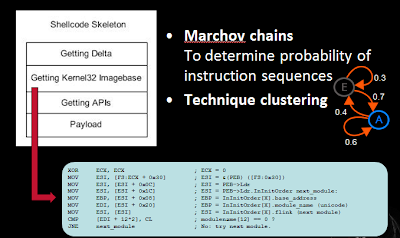

Shifting away from analysis of files, we can also attempt to classify shellcode on the wire from normal traffic. Using marchov chains which is a discipline of Artificial Intelligence, but in the realm of natural language processing, we can determine and analyze a network stream of instructions to see if the sequence of instructions are likely to be exploit code.

The Future of Automated Malware Generation

In many cases the path of attack and defense techniques follows the same story of cat and mouse. Just like Tom and Jerry, the chase continues forever, in the context of security, new technology is introduced, new attacks then emerge and in response new countermeasures are brought in to the detection of those attacks…an attacker’s game can come to an end IF they makes a mistake, but whereas cyber-criminal organizations can claim a binary 0 or 1 success or failure, defense can never really claim a victory over all it’s attackers. It’s a “game” that must always continue.

That being said you’ll hear more and more products and security technologies talk about machine learning like it’s this unbeatable new move in the game….granted you’ll hear it mostly from savvy marketing, product managers or sales folks. In reality it’s another useful layer to slow down an attacker trying to get to their end goal, but it’s by no means invincible.

Use of machine learning can be taken circumvented by an attacker in several possible ways:

- Likelihood of false positives / false negatives due to weak training corpus

- Circumvention of classification features

- Inability to parse/extract features from content

- Ability to poison training corpus

Conclusion

In reality, we haven’t yet seen malware that contains anti machine learning classification or anti-clustering techniques. What we have seen is more extensive use of on-the-fly symmetric-key encryption where the key isn’t hard-coded in the binary itself, but uses something unique about the target machine that is being infected. Take Zeus for example that makes use of downloading an encrypted binary once the machine has been infected where the key is unique to that machine, or Gauss who had a DLL that was encrypted with a key only found on the targeted user’s machine.

What this accomplishes is that the binary can only work the intended target machine, it’s possible that an emulator would break, but certainly sending it off to home-base or the cloud for behavioral and static analysis will fail, because it simply won’t be able to be decrypted and run.

Most defensive techniques if studied, targeted and analyzed can be evaded — all it takes is time, skill and resources. Using Machine learning to detect malicious executables, exploits and/or network traffic are no exception. At the end of the day it’s important that you at least understand that your defenses are penetrable, but that a smart layered defense is key, where every layer forces the attackers to take their time, forces them to learn new skills and slowly gives away their resources, position and possibly intent — hopefully giving you enough time to be notified of the attack and cease it before ex-filtration of data occurs. What a smart layered defense looks like is different for each network depending on where your assets are and how your network is set up, so there is no way for me to share a one-size fits all diagram, I’ll leave that to you to think about.

Useful Links:

Coursera – Machine Learning Course

CalTech – Machine Learning Course

MLPY (https://mlpy.fbk.eu/)

PyML (http://pyml.sourceforge.net/)

Milk (http://pypi.python.org/pypi/milk/)

Shogun (http://raetschlab.org/suppl/shogun) Code is in C++ but it has a python wrapper.

MDP (http://mdp-toolkit.sourceforge.net) Python library for data mining

PyBrain (http://pybrain.org/)

Orange (http://www.ailab.si/orange/) Statistical computing and data mining

PYMVPA (http://www.pymvpa.org/)

scikit-learn (http://scikit-learn.org): Numpy / Scipy / Cython implementations for major algorithms + efficient C/C++ wrappers

Monte (http://montepython.sourceforge.net) a software for gradient-based learning in Python

Rpy2 (http://rpy.sourceforge.net/): Python wrapper for R

About Stephan

Stephan Chenette has been involved in computer security professionally since the mid-90s, working on vulnerability research, reverse engineering, and development of next-generation defense and attack techniques. As a researcher he has published papers, security advisories, and tools. His past work includes the script fragmentation exploit delivery attack and work on the open source web security tool Fireshark.

Stephan is currently the Director of Security Research and Development at IOActive, Inc.

Twitter: @StephanChenette