There are multiple facilities, devices, and systems located on ports and vessels and in the maritime domain in general, which are crucial to maintaining safe and secure operations across multiple sectors and nations.

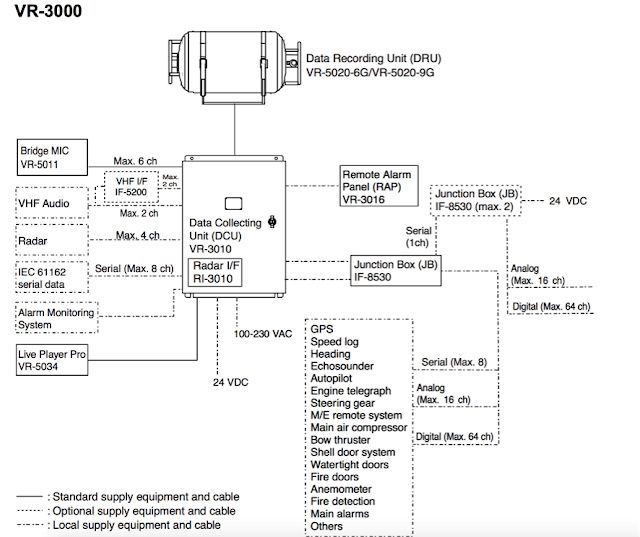

This blog post describes IOActive’s research related to one type of equipment usually present in vessels, Voyage Data Recorders (VDRs). In order to understand a little bit more about these devices, I’ll detail some of the internals and vulnerabilities found in one of these devices, the Furuno VR-3000.

(http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Navigation/Pages/VDR.aspx ) A VDR is equivalent to an aircraft’s ‘BlackBox’. These devices record crucial data, such as radar images, position, speed, audio in the bridge, etc. This data can be used to understand the root cause of an accident.

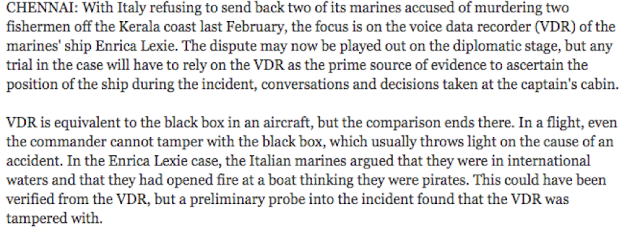

Several years ago, piracy acts were on the rise. Multiple cases were reported almost every day. As a result, nation-states along with fishing and shipping companies decided to protect their fleet, either by sending in the military or hiring private physical security companies.

Curiously, Furuno was the manufacturer of the VDR that was corrupted in this incident. This Kerala High Court’s document covers this fact: http://indiankanoon.org/doc/187144571/ However, we cannot say whether the model Enrica Lexie was equipped with was the VR-3000. Just as a side note, the vessel was built in 2008 and the Furuno VR-3000 was apparently released in 2007.

During that process, an interesting detail was reported in several Indian newspapers.

http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/voyage-data-recorder-of-prabhu-daya-may-have-been-tampered-with/article2982183.ece

From a security perspective, it seems clear VDRs pose a really interesting target. If you either want to spy on a vessel’s activities or destroy sensitive data that may put your crew in a difficult position, VDRs are the key.

Understanding a VDR’s internals can provide authorities, or third-parties, with valuable information when performing forensics investigations. However, the ability to precisely alter data can also enable anti-forensics attacks, as described in the real incident previously mentioned.

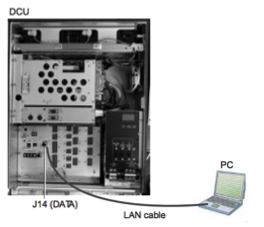

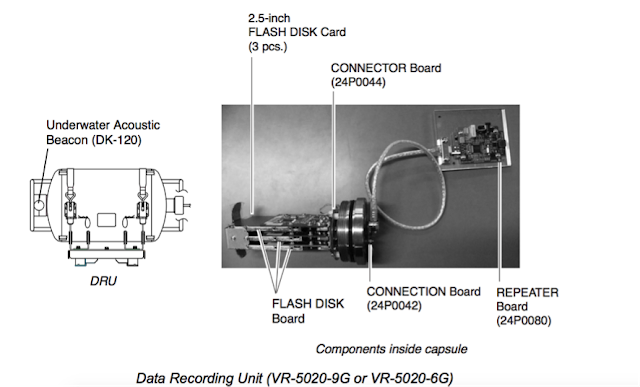

Basically, inside the Data Collecting Unit (DCU) is a Linux machine with multiple communication interfaces, such as USB, IEEE1394, and LAN. Also inside the DCU, is a backup HDD that partially replicates the data stored on the Data Recording Unit (DRU). The DRU is protected against aggressions in order to survive in the case of an accident. It also contains a Flash disk to store data for a 12 hour period. This unit stores all essential navigation and status data such bridge conversations, VHF communications, and radar images.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) recommends that all VDR and S-VDR systems installed on or after 1 July 2006 be supplied with an accessible means for extracting the stored data from the VDR or S-VDR to a laptop computer. Manufacturers are required to provide software for extracting data, instructions for extracting data, and cables for connecting between a recording device and computer.

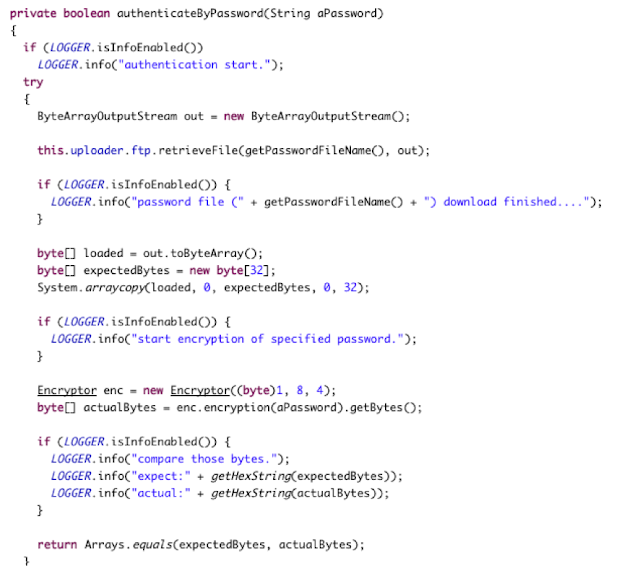

Take this function, extracted from from the Playback software, as an example of how not to perform authentication. For those who are wondering what ‘Encryptor’ is, just a word: Scytale.

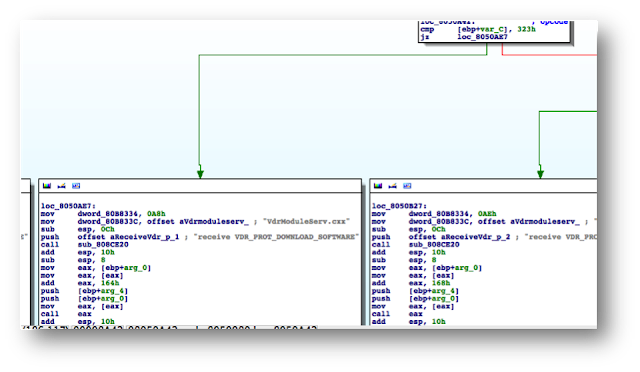

VR-3000’s firmware can be updated with the help of Windows software known as ‘VDR Maintenance Viewer’ (client-side), which is proprietary Furuno software.

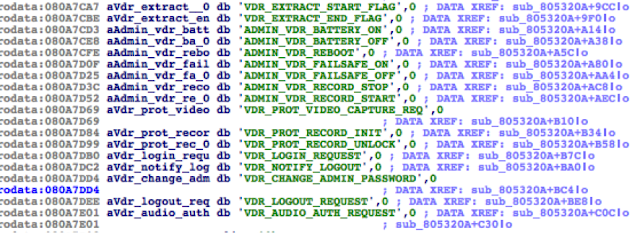

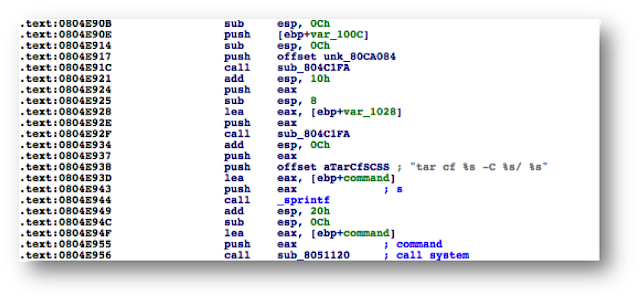

The VR-3000 firmware (server-side) contains a binary that implements part of the firmware update logic: ‘moduleserv’

This service listens on 10110/TCP.

Internally, both server (DCU) and client-side (VDR Maintenance Viewer, LivePlayer, etc.) use a proprietary session-oriented, binary protocol. Basically, each packet may contain a chain of ‘data units’, which, according to their type, will contain different kinds of data.

At this point, attackers could modify arbitrary data stored on the DCU in order to, for example, delete certain conversations from the bridge, delete radar images, or alter speed or position readings. Malicious actors could also use the VDR to spy on a vessel’s crew as VDRs are directly connected to microphones located, at a minimum, in the bridge.

Before IMO’s resolution MSC.233(90) [3], VDRs did not have to comply with security standards to prevent data tampering. Taking into account that we have demonstrated these devices can be successfully attacked, any data collected from them should be carefully evaluated and verified to detect signs of potential tampering.