Introduction

Phishing-resistant multi-factor authentication (MFA), particularly FIDO2/WebAuthn, has become the industry standard for protecting high-value credentials. Technologies such as YubiKeys and Windows Hello for Business rely on strong cryptographic binding to specific domains, neutralizing traditional credential harvesting and AitM (Adversary-in-the-Middle) attacks.

However, the effectiveness of these controls depends heavily on implementation and configuration. Research conducted by Carlos Gomez at IOActive has identified a critical attack vector that bypasses these protections not by breaking the cryptography, but by manipulating the authentication flow itself. This research introduces two key contributions: first, the weaponization of Cloudflare Workers as a serverless transparent proxy platform that operates on trusted Content Delivery Network (CDN) infrastructure with zero forensic footprint; second, an Authentication Downgrade Attack technique that forces victims to fall back to phishable authentication methods (such as push notifications or OTPs) even when FIDO2 hardware keys are registered.

This research was first disclosed at OutOfTheBox 2025 (OOTB2025) in Bangkok during the talk “Cloud Edge Phishing: Breaking the Future of Auth,” in which the technical methodology and operational implications were presented to the security community.

In this post, we will analyze the technical mechanics of this attack, which utilizes a transparent reverse proxy on serverless infrastructure to intercept and modify server responses in real-time. We will explore the weaponization of Cloudflare Workers, the specific code injections used to hide FIDO2 options, and the business implications of this configuration gap.

Before diving into the technical mechanics, it is important to understand the strategic implication: this is not a theoretical vulnerability. IOActive has operationalized this technique to demonstrate how trusted, serverless infrastructure can neutralize FIDO2 protections without breaking cryptography.

- The Innovation: We weaponized Cloudflare Workers to create an invisible, zero-cost proxy that blends with legitimate enterprise traffic, proving that adversaries no longer need expensive and potentially easier to detect infrastructure to succeed.

- Business impact: Instead of investing a substantial capital in hardware keys (often over $500k), attackers can use free-tier tools if “mixed mode” authentication policies are left open.

- How we can help: IOActive helps organizations validate their actual resilience against these “Living off the Trusted Land” attacks. We move beyond standard testing to simulate sophisticated threat actors and provide you with recommendations to protect your assets against modern, real-world attack vectors.

The Evolution of Phishing Infrastructure

To understand the context of this attack, we must understand the shift in adversary infrastructure. Traditional phishing operations relied on dedicated Virtual Private Servers (VPS), which left identifiable footprints such as static IP addresses, ASN reputation issues, and hosting provider abuse contacts.

More sophisticated threat actors have migrated to serverless platforms. This architecture offers distinct advantages for offensive operations:

- Distributed Network: Traffic originates from trusted CDNs, blending with legitimate enterprise traffic.

- Ephemeral Existence: Functions execute on demand and leave minimal forensic artifacts.

- Cost Efficiency: Massive scale is available for negligible cost.

Weaponizing Cloudflare Workers: The Invisible Proxy

As part of this research, we developed a weaponized proof-of-concept utilizing Cloudflare Workers to function as an invisible, transparent proxy. This tool sits between the victim and the Identity Provider (IdP), intercepting traffic in real-time.

By leveraging Cloudflare’s global edge network, the attack infrastructure gains immediate SSL/TLS legitimacy, high reputation, and resilience against traditional IP-based blocking. This aligns with recent threat intelligence trends where threat actors are increasingly “Living off the Trusted Land” (LotTL).

Recent industry reports confirm that this is not theoretical. Malicious groups such as 0ktapus and Scattered Spider have been observed adopting similar serverless techniques to target high-profile organizations, moving away from static infrastructure to evade detection. Our tool demonstrates that this capability is accessible and highly effective against standard MFA configurations.

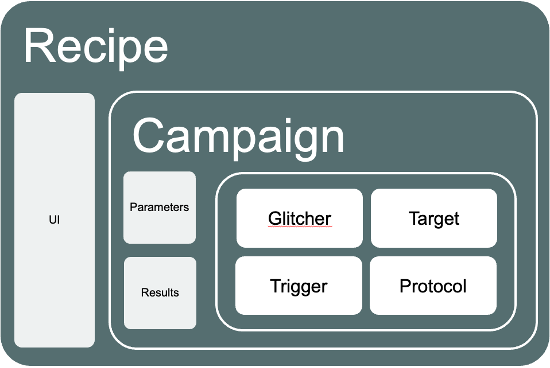

Understanding the Transparent Proxy Architecture

The core component of this attack is a transparent reverse proxy that rewrites domains bidirectionally. Unlike generic reverse proxies, this tool is aware of the specific identity provider’s protocol (in this case, Microsoft Entra ID).

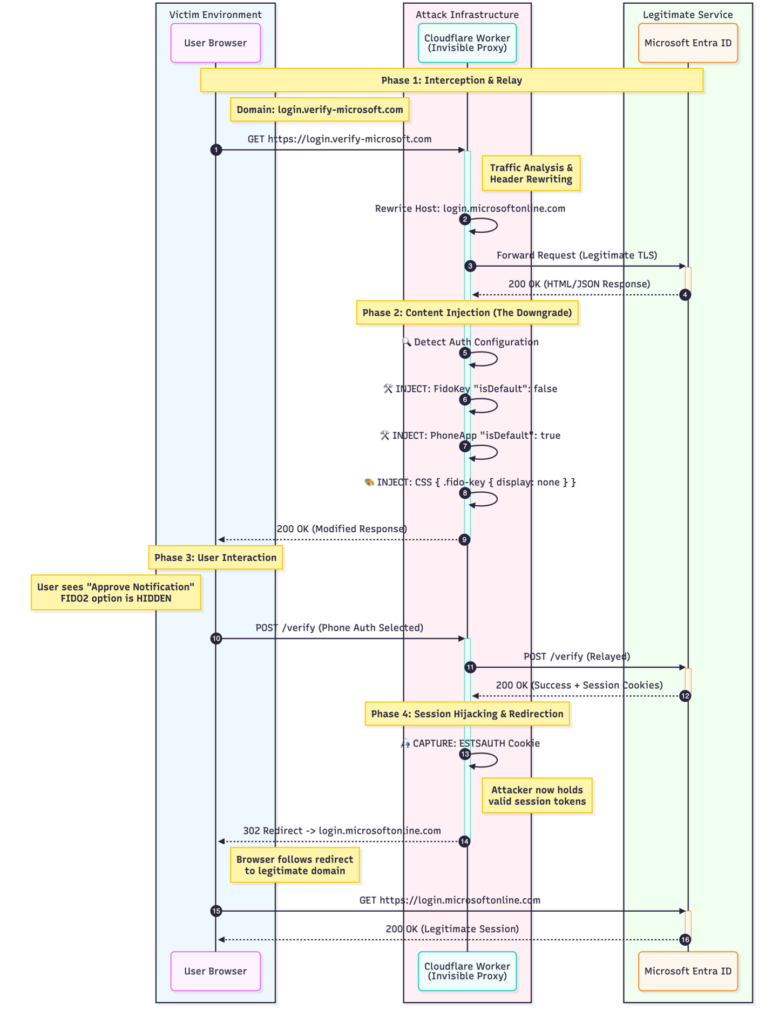

The attack unfolds across four phases:

- Phase 1: The victim accesses what appears to be a legitimate Microsoft login domain. The Cloudflare Worker intercepts this request and performs header rewriting to transform the phishing domain into the legitimate Microsoft endpoint.

- Phase 2: As the legitimate response from Microsoft flows back through the proxy, the Worker injects malicious payloads that alter the authentication configuration.

- Phase 3: The victim interacts with what appears to be an authentic Microsoft interface, unaware that available authentication methods have been manipulated.

- Phase 4: Once the victim completes authentication using a phishable method, the Worker captures session tokens and cleanly redirects the victim to the legitimate domain.

The diagram below illustrates this complete workflow, showing how traffic flows between the victim’s browser, the Cloudflare Worker infrastructure, and Microsoft’s authentication servers. Note the bidirectional domain rewriting that occurs at each stage, and the injection points where malicious modifications are introduced into otherwise legitimate responses.

This architecture is effective because every component appears legitimate to both parties. The victim sees authentic Microsoft content served over HTTPS with valid certificates. Microsoft sees legitimate authentication requests coming from IP addresses belonging to Cloudflare’s trusted infrastructure. The only modification happens in transit, within the Worker’s edge execution environment.

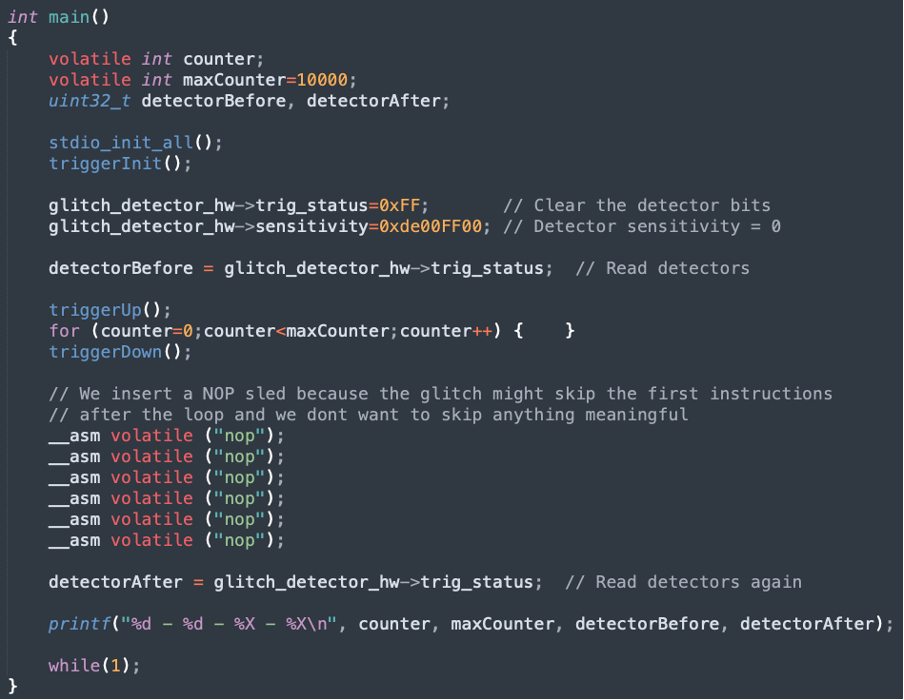

Technical Deep Dive: Authentication Downgrade

The attack exploits an implementation gap in how modern authentication interfaces present available methods. These interfaces often render authentication options client-side based on a JSON configuration object sent by the server. When an attacker controls the traffic flow, they can modify this configuration in transit to influence which authentication methods are presented to the user.

We have identified two primary techniques: JSON Configuration Manipulation (true downgrade) and CSS Injection (visual elimination).

Method 1: JSON Configuration Manipulation

This is the preferred technique. When a user authenticates, the IdP sends a JSON object defining the available authentication methods and which one should be the default. By modifying this configuration, the attacker downgrades the authentication priority from phishing-resistant FIDO2 to phishable push notifications.

Pre-Injection State (Legitimate Response)

The server sends a configuration where FidoKey is set to isDefault:true.

[

{"authMethodId":"FidoKey", "isDefault":true, "display":"Security key"},

{"authMethodId":"PhoneAppNotification", "isDefault":false, "display":"Microsoft Authenticator"}

]JSON Injection Logic

The proxy uses regular expressions to locate these keys and invert their boolean values. The goal is to set FIDO2 to false and a phishable method (like PhoneAppNotification) to true.

// Change FIDO2 from default to non-default

content = content.replace(

/("authMethodId":"FidoKey"[^}]*"isDefault":)true/g,

'$1false'

);

// Force Phone App Notification as default

content = content.replace(

/("authMethodId":"PhoneAppNotification"[^}]*"isDefault":)false/g,

'$1true'

);

Post-Injection State (Malicious Response)

The victim’s browser receives a valid configuration telling it to prompt for the Microsoft Authenticator app instead of the FIDO2 key. The user, seeing a familiar prompt, accepts the notification. The server accepts this as a valid login because Phone Authentication is a legitimate, enabled method for that user.

Demonstration: JSON Downgrade in Action

The following videos demonstrate this JSON manipulation technique in practice.

Baseline: Legitimate FIDO2 Authentication

The video below shows a legitimate authentication flow where FIDO2 is functioning as designed. The user navigates to the Microsoft login portal, enters credentials, and is presented with the option to authenticate using a hardware security key. Upon selecting this option and inserting the key, cryptographic challenge-response occurs between the browser and the FIDO2 token.

This is the intended security model. The FIDO2 key performs asymmetric cryptographic operations that are bound to the legitimate domain. Any attempt to phish these credentials would fail because the key would refuse to sign challenges for domains other than login.microsoftonline.com.

Attack: JSON Configuration Manipulation

The next video demonstrates the JSON downgrade attack in isolation. The user’s authentication attempt is routed through our transparent proxy deployed on Cloudflare Workers. As the authentication configuration is transmitted from Microsoft to the victim’s browser, the Worker intercepts the response and modifies the JSON payload using the regex patterns discussed earlier. The FidoKey method is set to non-default, while PhoneAppNotification is promoted to the primary method.

Observe the change. Instead of being presented with the security key option as the primary method, the interface now suggests push notification authentication. The user, trusting the familiar Microsoft interface and seeing no security warnings, approves the notification on their phone. The authentication succeeds normally from both the user’s and server’s perspectives.

Method 2: CSS Injection

This technique does not perform a downgrade in the traditional sense. Instead, it surgically removes the FIDO2 option from the user’s view entirely. The attacker injects a <style> block into the HTML <head> that hides specific DOM elements corresponding to the security key authentication method. The critical distinction is that this gives the user no choice. The option to use FIDO2 is completely eliminated from the interface, forcing them to use the remaining phishable methods.

CSS Injection Logic

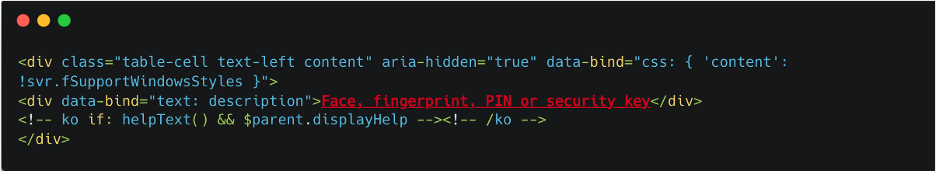

The proxy injects CSS rules targeting the specific data attributes and ARIA labels used by the IdP’s frontend framework.

const fidoHideCSS = `

<style>

div[data-value="FidoKey"],

div[data-test-cred-id="7"],

div[aria-label*="security key"],

div[aria-label*="Face, fingerprint, PIN or security key"] {

display: none !important;

}

</style>`;

content = content.replace(‘</head>’, fidoHideCSS + ‘</head>’);

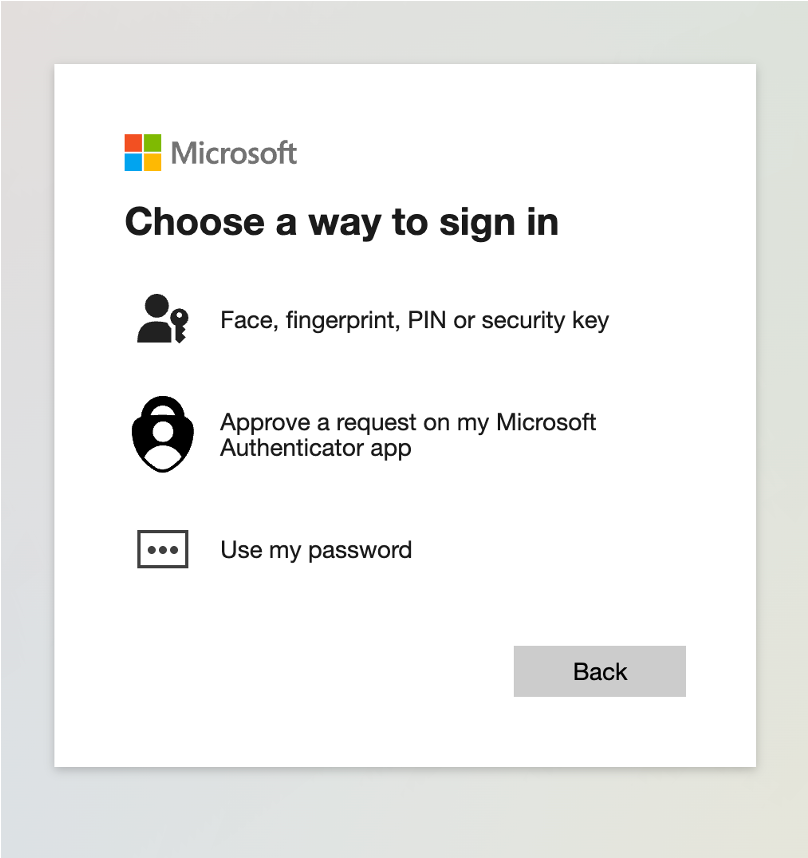

Visual Impact: Eliminating User Choice

The following analysis demonstrates how the CSS injection surgically removes FIDO2 options while maintaining the appearance of a legitimate Microsoft authentication flow. Unlike the JSON manipulation which changes priorities, this technique completely eliminates the option. The user has no ability to select FIDO2 even if they wanted to.

When a user with FIDO2 configured attempts to authenticate through the legitimate Microsoft portal, they are presented with a clear option to use their hardware security key. The interface displays “Sign in with a security key” prominently.

In the standard authentication flow shown above, Microsoft’s interface presents all available authentication methods. The security key option is rendered as an interactive element that the user can select.

However, when the same authentication attempt flows through our transparent proxy with CSS injection enabled, the user experience changes. The proxy has already injected malicious CSS rules targeting specific DOM elements. The underlying HTML structure that Microsoft’s authentication framework generates remains unchanged.

The image above shows the actual HTML source as it would appear in the user’s browser after being processed by Microsoft’s authentication server. Note the specific attributes: data-value=”FidoKey” and the ARIA labels that identify the security key authentication method. These are the precise selectors our CSS injection targets.

The key insight is that while the HTML elements are still present in the DOM, our injected CSS renders them invisible. The browser’s layout engine processes the display: none !important rule, removing these elements from the visible page without modifying the underlying HTML structure.

The above screenshot shows the HTML structure with the targeted elements highlighted in the browser’s developer tools. The div[data-value=”FidoKey”] element is still present in the DOM tree, maintaining the page’s structural integrity. However, the applied CSS styling has set its display property to none, making it completely invisible to the user.

The final result from the victim’s perspective is shown below. The interface appears completely normal: authentic Microsoft branding, legitimate TLS certificates, correct domain (from their perspective), and familiar UI patterns. The only difference is that the security key option has vanished entirely. The user is not given a choice. They cannot select FIDO2 even if they recognize something is wrong.

From the user’s perspective, this appears to be a normal authentication flow. There are no browser warnings, no certificate errors, no visual indicators that anything has been manipulated. The user has no option but to proceed with the phishable methods available.

Demonstration: CSS Injection in Action

The following video demonstrates the CSS injection technique applied during authentication. This captures the moment when the FIDO2 option is eliminated from the interface through injected CSS styling.

This demonstration shows the user interface before and after the CSS injection is applied. The FIDO2 option disappears seamlessly, leaving only the phishable authentication methods visible to the user.

Complete Attack Chain Demonstration

The following video demonstrates the complete end-to-end attack workflow from initial compromise to session hijacking. This recording captures the entire attack chain: the victim receives a phishing link, navigates to the attacker-controlled domain, enters their credentials, completes MFA using the downgraded method, and is seamlessly redirected to the legitimate Microsoft portal. Meanwhile, the attacker captures all necessary session tokens (ESTSAUTH and ESTSAUTHPERSISTENT) to hijack the session independently.

This demonstration shows why the attack is effective. The victim experiences what appears to be a normal authentication flow. There are no obvious red flags, no browser warnings about invalid certificates, no interface anomalies. After successful authentication, the user is redirected to the legitimate domain and can proceed with their work. From the security operations perspective, the logs show legitimate authentication using approved MFA methods from expected IP ranges (Cloudflare’s infrastructure). Traditional security monitoring systems would not flag this activity as suspicious.

Business Impact & Strategic View

The existence of this technique changes the ROI calculation for defensive security investments.

The Investment Gap

Organizations typically spend $50-$100 per employee to deploy FIDO2 hardware. For a 10,000-person enterprise, this is a capital expenditure of $500,000 to $1,000,000. However, if the configuration allows fallback to weaker methods, an attacker using a free Cloudflare Workers account (Cost: $0) can bypass this investment entirely.

Risk Assessment

- Target: Organizations with “mixed mode” authentication (FIDO2 + Mobile App/SMS).

- Adversary Value: Leveraging a downgrade attack, the adversary forces the authentication flow into a weaker state. This allows them to circumvent the physical hardware requirement and capture authenticated session cookies, granting full access without possessing the key.

- Impact: Complete account takeover despite hardware token possession.

- Visibility: Low. The logs show a legitimate user authenticating with a legitimate method (Phone App).

Mitigation & Defense

The most effective defense against downgrade attacks is strictly enforcing method allow-lists via Conditional Access policies.

Recommended Actions

- Enforce FIDO2-Only Policies: Configure Conditional Access to require phishing-resistant MFA for all users provisioned with keys. Do not allow fallback to push notifications or SMS.

- Monitor Authentication Degradation: Create alerts for users who historically authenticate via FIDO2 but suddenly switch to weaker methods from novel IP addresses or locations.

- Red Team Validations: Regularly test the effectiveness of these policies. Deployment of hardware is not synonymous with protection; configuration must be validated against active downgrade attempts.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates a critical gap in how organizations approach phishing-resistant MFA deployment. While FIDO2’s cryptographic properties remain sound, its security model assumes that users will always have the option to select it. When threat actors control the communication channel through serverless proxies, they can manipulate this assumption at the presentation layer, either by downgrading priorities through JSON manipulation or by completely eliminating secure options through CSS injection.

The implications extend beyond technical implementation. Organizations investing hundreds of thousands in hardware security key deployments often operate under the assumption that this investment inherently protects them. The reality, as demonstrated through this weaponized Cloudflare Workers implementation, is that adversaries can bypass million-dollar security investments using free-tier serverless infrastructure and several dozen lines of JavaScript.

The attack surface is not the cryptography, it is the configuration gap. Modern authentication systems prioritize flexibility and backward compatibility, allowing multiple authentication methods to coexist. This design decision, while operationally necessary, creates the attack vector. When policies do not enforce exclusive use of phishing-resistant methods, attackers exploit the weakest link in the authentication chain by ensuring users never see the strongest option.

From a defensive perspective, three critical actions emerge.

First, policy enforcement must be absolute. Conditional Access policies should mandate phishing-resistant MFA without fallback mechanisms for users provisioned with FIDO2 keys. The operational friction of lost keys is significantly less costly than a compromised executive account.

Second, behavioral monitoring must detect method degradation. Users who consistently authenticate with FIDO2 but suddenly switch to push notifications from anomalous geographic locations represent a high-confidence indicator of active compromise attempts.

Third, red team validation must simulate real adversary TTPs. This research demonstrates techniques that sophisticated threat actors are already using. Organizations must test their defenses against serverless-based transparent proxies, not theoretical attack models from five years ago.

The serverless paradigm has fundamentally shifted the economics of phishing infrastructure. Threat actors no longer need dedicated servers, static IP addresses, or significant capital investment. They leverage trusted CDN infrastructure, benefit from immediate SSL legitimacy, and operate with minimal forensic footprint. Defensive strategies must evolve accordingly.

This work, conducted by Carlos Gomez at IOActive, highlights the importance of adversary simulation in identifying the gap between security investments and actual protection. The techniques presented here are not hypothetical. They represent the current state of sophisticated phishing operations.

IOActive has fully operationalized these advanced tradecrafts within our Red Team engagements, deploying weaponized infrastructure and proprietary tooling to mirror real-world threat agility.

Organizations that understand this gap can close it through proper configuration and enforcement. Those that do not will continue to invest in security theater while remaining vulnerable to basic manipulation of the authentication flow.